Think of your best friend, a friend that knows all your ticks, hobbies and vices. Now imagine this friend happens to be a doctor, and she’s your doctor. Since she’s your bestie, she lets you swing by the office for impromptu visits. She emails you, she patiently answers all your questions even if it takes an hour, and she encourages you to call her personal cell — “It’s cool, I promise!” — even on Sunday morning when she’s at the farmers market.

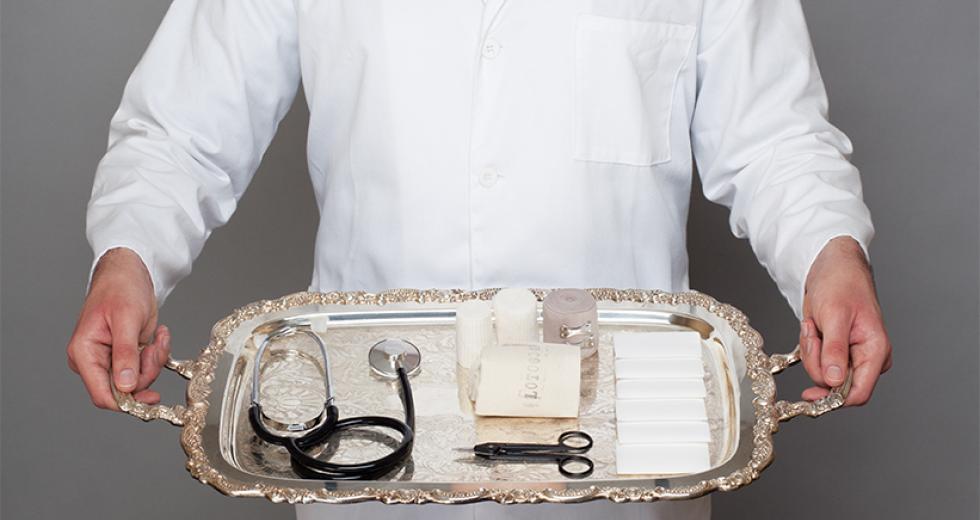

This is concierge medicine. It’s a growing niche of health care that provides longer office visits, customized treatment and 24/7 access to your doctor. The term itself might be misleading, as the word concierge has the whiff of the upper crust, suggesting white-gloved servants, $9 bottled water and vaguely European accents.

“We don’t like the name concierge medicine because it connotes this elitist mentality,” says Michael Tetreault, the editor-in-chief of Concierge Medicine Today. “We hear things like, ‘Oh yeah, that’s the expensive care. That’s what Paris Hilton and the celebrities get.’ Nothing could be further from the truth.”

The average cost of a concierge plan — which, to clarify, is not comprehensive insurance — is roughly $150 a month, paid directly to the doctor. According to Tetreult, half of the patients have a household income of less than $100,000, and top-level executives account for less than 3 percent of the members.

Roughly 5,500 doctors practice concierge medicine with an estimated 1.5 million patients nationwide. Why so few? Tetreault chalks it up to a PR problem. “People really don’t understand that it’s affordable, that it’s not just for the rich.” And they can be hard to find: In more rural areas like South Dakota or Mississippi, sometimes only a handful of doctors serve an entire state. And while critics question its basic fairness — Are the rich getting healthier while the poor get sicker? — concierge doctors say they can now spend more time helping patients, less time mucking with paperwork, and they point to new studies suggesting it can actually lower the cost of health care.

Hamster-wheel medicine

Crowded lobbies, long waits and squabbles over insurance followed by 6-minute visits while the doctor skims your file and tries to remember your name: These are the standard complaints of most patients, and things are just as bad for many physicians, who are practicing what Tetreult calls hamster-wheel medicine.

Take Dr. Kristine Burke, who had a traditional practice in Sacramento for 13 years. “That old model is based on higher volume, more patients. As time went on, I became increasingly frustrated with the lack of time to really help people change their health,” she says. Then, in 2009, she attended a conference for the American Academy of Private Physicians (AAPP). She saw it as a game-changer. “I was in a room of happy, satisfied, passionate doctors. It was a novel experience.” She made the switch and hasn’t looked back.

Some doctors are switching as a matter of necessity.

“You can’t see a patient in five or six minutes. That’s just impossible if you’re really going to do your job,” says Dr. Marcy Zwelling, who practices in Los Alamitos and goes by Dr. Z. “I was constantly behind; it was almost a running joke. When I saw a patient at midnight — it was the only time that I could see her, and I had to see her because her nephew had just committed suicide — it was clear that I couldn’t do my job. Patients weren’t getting the care they needed.” She then overhauled her practice, slashing her patient list from 4,000 to 500.

“When you think of Andy Griffith-style medicine, the doctor had a clinic in the local town. It’d be strange for him to say, ‘What kind of insurance does Opie have?’”

Michael Tetreault, editor in chief, Concierge Medicine Today

Visits are longer. The waits are shorter. This gives physicians like Dr. Burke the bandwidth to personally field phone calls from patients — even on a Saturday night. Skeptical, I asked Dr. Burke if it was really (really?!?) OK to call her on the weekend.

Admittedly, she says the idea of allowing patients access to her cell phone number scared her at first. “But because you have a small number of patients and you know them very well, we’re able to take care of almost everything during business hours, since we have time to address them and we have a relationship. So they don’t want to bother me unless it’s important, and if it’s important, I want to hear about it.” When a patient called her recently on the weekend about a urinary tract infection, she was happy to get the call because she could immediately diagnose the problem and prescribe treatment.

But how will this impact the overall health care market? The industry is already pinched by a shortage of primary care physicians, and when a doctor guts his roster from 4,000 to 500, what happens to the other 3,500? Tetreault says that the impact is unlikely to result in a mass of untreated patients, as 85 percent of concierge doctors also take traditional insurance. So the only affected patients are from the 15 percent of concierge doctors who switch entirely (fewer than 1,000 have done so), a small enough figure that, according to Concierge Medicine Today, it can be absorbed by standard providers. Still, critics wonder if this exacerbates a divide between the healthy and the sick, the rich and the poor.

“I don’t see myself as a concierge kind of guy. If I were to join, how many of my patients would lack the resources to join me?” wrote Dr. Steve Dudley in an op-ed for the Los Angeles Times. “I’d have to leave Ann Marie behind. She has a developmental delay and has been my patient ever since I started in practice. I’d leave the scores of young adults who are just starting out in their careers and find it a stretch to come up with their co-pays.”

To be blunt, are doctors just switching to concierge medicine so that they can work cushier hours and make more money? Dr. Zwelling says she actually makes less money with concierge medicine. “My marketplace is absolutely middle class,” she says. She priced her plan by calculating the number of patients she could see in a year, allowing time for at least one annual 90-minute session, and then worked backward to arrive at $125/month. “We’ve always had the same business strategy. We don’t nickel and dime. Patients pay once, and that’s it. And they can see me whenever they want.”

Dr. Chris Ewin, a Texas-based concierge advocate, bristles at the notion that he only serves the rich. He says many of his patients are unemployed or blue-collar workers and that, in some ways, his services can prove more affordable than other alternatives. “I have a patient who had a Vicodin addiction, and he spent $50 a day on his drug habit and he worked at Taco Bell,” he says. “Now his addiction is gone, and I only charge him $5 a day. I had someone come in — an immigrant — who mows lawns for a living. He has diabetes. He looked at me and said, ‘Wait, all I have to do is mow two lawns a month, and I can call the doctor all I want?’”

Concierge medicine may prove fiscally responsible as well. A study from MDVIP, a network of private physicians, found a 72-percent reduction in hospital admissions for concierge patients and a savings of more than $2,000 a year for each concierge patient. Doctors who engage in this practice can save the economy billions of dollars, according to Dr. Zwelling, by working with their patients on preventative care, staving off serious ailments and trips to the ER.

Too good to be true? Possibly. Skeptics question whether these results have selection bias, meaning concierge patients are wealthier and healthier and therefore less likely to go to the hospital in the first place. Dan Hecht, the CEO of MDVIP, says the selection bias is “very minimal,” but, like most issues with health care, there is debate.

Is it worth it?

Since concierge medicine is not insurance (it wouldn’t cover a trip to the hospital) many patients combine it with a high-deductible plan. Tetreault suggests that consumers think of health insurance more like auto insurance or fire insurance; it should be used for emergencies, not the day-to-day. You wouldn’t use car insurance to change your oil, rotate the tires or buy wiper blades. In the best-case scenario, the sum of the concierge fee ($150/month, for example) plus the bare-bones premiums for a high-deductible plan ($110-ish, theoretically) would pencil out to less than $328 per month, or what the Department of Health and Human Services cites as the “average” cost of health care.

But is there really a health benefit to switching, or is this specialized service just pampering?

According to Dr. Burke, the benefits can actually save lives. “I now have the time to listen to a patient’s story, not just hear the bullet-list of symptoms,” she says. She can work with patients to discover how their life experiences impact what she calls “the web of their biological system.”

This does two things: 1) It boosts the odds of catching a problem; and 2) It nudges patients toward healthier behavior. As an example, she points to the cheeseburger. “It’s easy to say, ‘Burgers can be bad for you.’ But that doesn’t really change anyone’s behavior. Now, I have the time to help them understandspecifically how that burger impacts their bio-chemistry. I can explain how the refined carbs in the flour of the hamburger bun set off a cascade of chemical signals that make your cells more resistant to insulin which, in turn, leads to diabetes. Now that means something.”

There’s also the benefit of what Dr. Ewin calls fine-tuning, working with a patient to make incremental changes to their blood pressure, diabetes or cholesterol. And when something bigger comes up, the concierge doctor can tap into her connections and route patients to the right specialist.

“I had a 12-year-old with a thyroid nodule who needed surgery. It was just a phone call for me to get her into the surgeon,” Dr. Ewin says. “Otherwise, it could have taken forever — and it was a mass that could have been cancerous.”

When I called Dr. Ewin’s office, I was charmed to find that his outgoing voicemail includes his cell number. He views his accessibility as the potential difference between life or death. “They’ve got their best friend on the phone when they call me. And if something comes up and they don’t call me, I’ll say, ‘What are you doing?! If you called me the first day you saw symptoms, I could have treated you!’”

The Future is The Past

And then, of course, there’s the Affordable Care Act. While the jury is still out on whether the overall cost of health care will rise or fall as a result of the ACA, there seems to be consensus that some patients, at the very least, will see a rise in premiums. If this is the case, then concierge medicine might look more appealing by contrast. Tetreault is already seeing that impact, saying, “We’ve found that since Obamacare, so many more patients are looking for an alternative to their current way of insurance. They’re finding that their employer plans are too expensive, so they would rather find a high-deductable option at considerable savings. Given this dynamic, Concierge Medicine Today predicts the annual growth rate to be somewhere between 7 to 15 percent.

In a sense, concierge medicine is simply a throwback to a bygone era. Look at health care before the 1960s, when doctors toted stethoscopes and actually paid house calls. “This is not a new concept of medicine. It’s more of an old-fashioned medicine brought into a modern marketplace,” says Tetreault. “When you think of Andy Griffith-style medicine, the doctor had a clinic in the local town. It’d be strange for him to say, ‘What kind of insurance does Opie have?’”

Recommended For You

In Sickness and in Health

Medical insurance is available, but are the doctors?

Under the federal Affordable Care Act, all but a small number of Americans soon will be required to have health insurance. But having insurance is one thing; getting the medical care it is intended to cover may be entirely another.

Going Meta-Care

Obamacare presents a radical shift in Medicare delivery

As Obamacare begins to take effect in hospitals across the country, it’s becoming clear that the new financial model for Medicare is the polar opposite of a government takeover.