I am currently on SSDI (Social Security Disability Insurance), retired after getting colon cancer and advanced Hep C. I had been on intermittent disability and could no longer provide for my family. I would like to get back to (a) work program and reestablish my worth using my experience and skills to become a member of the workforce while saving and becoming a homeowner once again if given the opportunity for a second chance of providing a better life for my wife and myself.

The emails kept pouring in. They came from individuals desperate for work, from stressed veterans, from parents who didn’t know where else to turn.

I have a 25 yr old son who has Down Syndrome looking to get back into the workforce. He could not wear a mask during Covid-19 restrictions and had to quit his job, but now needs help getting back into the workforce. He could use the job coaching support, too.

Managers at PRIDE Industries read every one and responded with helpful resources. But it was clear that PRIDE, a 55-year-old nonprofit social enterprise with a mission to help people with disabilities find jobs, could do more. And in the throes of a global pandemic, there was much more that needed to be done.

“You can read these emails and feel the desperation in some of them,” says Leah Burdick, PRIDE’s chief growth officer. “We would send them in the right direction for help, but there was no formal tracking process around it.”

This would soon change.

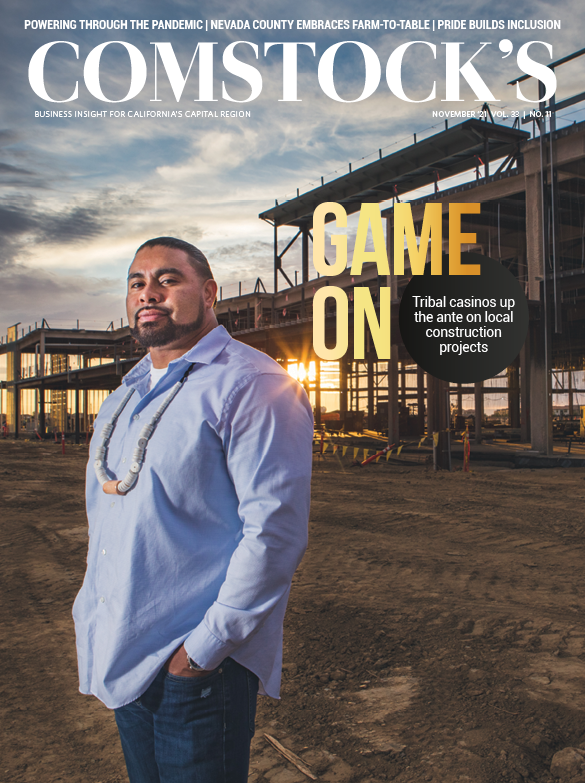

From its beginnings in a church basement in Auburn to its current status as the Capital Region’s leading employer of people with disabilities and other hurdles to employment (including former foster youth and veterans), PRIDE Industries represented the idea of an inclusive workforce before it was trending. The organization employs individuals in fields such as manufacturing and logistics, and facilities management, and provides recruitment and staffing with an ultimate goal to create 100,000 jobs for people with disabilities. But like the rest of the world, PRIDE felt the burn of 2020. Its longtime CEO, Michael Ziegler, passed away after guiding the Roseville-based enterprise for 37 years. Shutdowns due to COVID-19 forced the organization to reevaluate its strategies for growth.

But the future looks more expansive than ever. In June 2020, the board of directors chose Jeff Dern, who was named president by Ziegler in 2018, as the new CEO. (Dern is also a member of the Comstock’s Editorial Advisory Board.) After merging operations with two like-minded organizations (Crossroads Diversified Services in 2020 and Partnerships With Industry in 2021), Dern has a twofold vision for the future: to grow PRIDE’s operations, and to help other businesses design and implement their own inclusion programs through its Inclusive Talent Solutions Advisory Group.

“We open doors for people who have so much to contribute.” Dern says. “There’s no better feeling than being a part of a team that when we are successful someone’s life gets changed for the better. The success of PRIDE Industries is measured by each person whose life we impact with access, choice and greater independence through employment. It’s a privilege to be part of a company that offers hope to so many.”

“We want to create more access and more choice for jobs so that people with disabilities can meet their employment goals.”

Jeff Dern, CEO, PRIDE Industries

PRIDE employs 5,661 people, including 3,230 team members with disabilities, who make up nearly 60 percent of its workforce. But with the employment rate at around 30 percent for people with disabilities ages 16-64 in the U.S., fulfilling PRIDE’s “equal access for all” mission requires the joining of visionary forces.

“We want to create more access and more choice for jobs so that people with disabilities can meet their employment goals,” Dern says. “We do that by growing businesses within PRIDE to prove the model works and showing that any organization in the world can adopt a similar model.”

Leah Burdick joined PRIDE Industries as its chief growth officer

in 2020 with a goal to refresh the brand and expand the

Roseville-based social enterprise, which hires people with

disabilities to work in its warehouse. (Photo by Fred Greaves)

Growth Mindset

With a global marketing background, Burdick joined PRIDE Industries at the beginning of 2020 with big plans to refresh the brand and target more commercial businesses. “I had to build a world-class marketing team to rival companies I worked with,” says Burdick, who has an MBA in global management and worked for Jones Lang LaSalle, a Fortune 500 global commercial real estate firm. “We were starting that … then COVID hit and everything got blown up.”

This “baptism by fire,” as Burdick calls it, pushed initial plans back months. But the spirit of PRIDE kept the trains on the track. In 18 months, she expanded the marketing team, built a customer relationship management tool, rebuilt the foundation team (the philanthropic arm of the organization), and led a brand refresh, including a new website and job seekers helpline. In August, PRIDE completed a six-month pilot for its helpline (844 I-AM-ABLE), where job seekers can speak to someone directly for guidance. The number of calls went from 15 a month to 100 a month. After its successful trial, the helpline has become a permanent resource and PRIDE plans to bring on a Spanish speaker.

“(People with disabilities) are very creative problem solvers and they have a unique perspective on the world. These qualities are valuable for businesses trying to be competitive.”

Leah Burdick, chief growth officer, PRIDE Industries

Before joining the organization, Burdick had to dig deep to find meaning in her career. In those corporate ecosystems, the end goal was always to serve the shareholders. But she knew there was more to life. Her 8-year-old son is adopted and Burdick had previously done volunteer work in the foster care world, creating Foster Coalition, an online resource for foster youth and parents. At PRIDE, she says, she can merge her passion and profession, helping give underrepresented populations a fighting chance.

“People with disabilities live in a world that wasn’t built for them,” Burdick says. “They are very creative problem solvers and they have a unique perspective on the world. These qualities are valuable for businesses trying to be competitive.”

Made in California

If anybody understands competition, Triathlon Hall of Famer Sally Edwards does. The ultramarathoner also has a history with PRIDE Industries that runs deep. In the early 1990s, PRIDE manufactured her company’s snow shoes and ultimately bought that business called YubaShoes. In 1993, Edwards founded Heart Zones, which makes heart rate training programs and devices. “We’re in the business of motivating and engaging people to move more,” Edwards says. “As Americans, we need more physical activity.”

Many American businesses work with manufacturers in Asia to cut down production costs. But the global pandemic made foreign parts harder to get. Shutdowns clogged up the supply chain, so companies had to pivot from thinking globally to thinking locally — a concept called reshoring, when a company brings its production and manufacturing back to its home country.

Edwards was unfamiliar with the term reshoring, but when she needed a regional partner to help make a new heart rate sensor, she once again (with a nudge from friend and Comstock’s publisher Winnie Comstock-Carlson) turned to PRIDE.

Heart Zones has two body-worn sensors and three equipment-enabled sensors (cycling, treadmills and rowers), Edwards says. In phase 1 of the partnership, PRIDE is making two component parts for the heart rate sensor: the strap and the attachment clips. The third component, the electronic device, will be made in phase 2.

For the heart rate sensor, Edwards had a part sample, but not the specs. She had to hire a company to get the precision measurements, which pushed the delivery date back. Despite the delays, Edwards doesn’t regret taking steps to source locally, and was relieved to know she had support within arm’s reach.

With more companies looking to make things stateside, PRIDE saw the opportunity to promote its social marketing advantage. Partnering with PRIDE for production means waste reduction, shorter delivery times and “you can put a label on your product that says, ‘Assembled with PRIDE by people with disabilities,’” Burdick says.

A Hand Up

Taggart Neal wanted to help another group in need of support: nurses. A U.S. Navy veteran, Neal launched his startup, TagCarts, to give nurses upgraded medical carts that make their jobs easier. When the pandemic hit, he created a new version: a single-use medical cart for nurses to avoid cross contamination at pop-up hospitals and temporary care facilities. He called them HeroCarts.

PRIDE became Neal’s assembly partner, where veterans handle inspections, packaging, fulfillment and shipping of HeroCarts. “I saw the nurses didn’t have carts,” he says. “PRIDE jumped in and said, ‘How can we help?’”

“Most big companies the size of PRIDE aren’t that humble and willing to lean down and give someone a hand up like that.”

Taggart Neal, founder, TagCarts

The relationship between Neal and PRIDE goes back about a decade. He first went to the organization in 2012 with his TagCarts idea. He wanted to have them made by veterans. In that initial meeting, they talked about designs, business plans and capital. Neal had none of those things then, but he recalls them telling him, “We’ll leave the door open.”

After that first meeting, he was disappointed by how unprepared he was. But PRIDE’s encouragement kept him motivated. Since then, Neal raised funds and employed nurses and an expert design team. In July 2019, he went back to PRIDE with the updated plans. The door, as promised, was still open. “Most big companies the size of PRIDE aren’t that humble and willing to lean down and give someone a hand up like that,” he says. “It’s amazing they’re that big and still willing to listen to the little guy.”

Now Hiring

This summer, a mother called the PRIDE helpline to support her 18-year-old adopted son, Jordan Cooney, who was methamphetamine positive when he was born.

To help him find a job, Carlos Perez, PRIDE’s youth services job developer, went with Cooney to the Westfield Galleria at Roseville to get him comfortable talking to employers. The mall was crowded. Cooney was nervous at first. But on their second visit, Cooney had more confidence and he soon landed his first job. At the movie theater, Cooney now works 16-20 hours a week at the concession stand and ushering. He says everybody is friendly and his managers have a positive energy. Another bonus is he gets to see a lot of movies. He likes superhero movies the most, like “The Avengers.” His recent favorite was “Black Widow.”

“It was a fun, action-packed movie,” Cooney says. “Plus, it showed more behind the scenes about what happened to “Black Widow.”

According to Burdick, hiring someone with a disability gives a business many advantages, including a strong work ethic and retention. When you give someone a chance who hasn’t had a chance before, she says, they want to show up and do a good job. “We’re waking up other businesses to the fact that they’re missing out,” Burdick says. “It hurts everybody when not all voices have a chance to contribute.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Startup of the Month: TagCarts

A veteran-owned startup looks to improve medical carts for health care professionals

Medical carts are mobile storage units for health care equipment, supplies and medication, and may include workstations for access to electronic data.

An Appreciation

Memories of former Pride Industries CEO Michael Ziegler

Whether we knew him as Michael, Mike or Ziggy, hundreds of us had a tendency to preface a reference to Michael Ziegler with two words: “my friend.”

Can Nonprofits Scale to Solve Community Problems?

It’s a familiar sentiment expressed by a local donor: The charity she supports is asking for money with increasing frequency. Yet nothing changes for the better, and now duplicate groups are popping up, all of them requesting funds to address the same problem. To her, the requests seem endless.

Organizational Misbehavior

Are you grooming or stifling tomorrow's leaders?

With the national economy stumbling along like a wounded animal, the only steady growth these days is in the number of workers being shown the door. But while layoffs can be demoralizing, those workers who remain on the job may find “the Great Recession” to be a huge career booster.