Infill or outpost? Sprawl or smart planning? How some people view the Cordova Hills development proposed for southern Sacramento County may depend on which end of Highway 50 they’re looking from.

In late January, Sacramento County supervisors approved a 2,688-acre development adjacent to Rancho Cordova into its general plan on a nearly unanimous vote. Besides approving the specifics of the massive and complex project, the 4-1 vote seemingly endorsed a new process for evaluating urban development that put increased emphasis on extensive regional collaboration and meeting highly detailed environmental criteria.

Nonetheless, Supervisor Phil Serna, the lone dissenting vote, blasted the project for what he believed was runaway and wasteful sprawl. Critics added the heated charge that Cordova Hills developer Ron Alvarado had tricked the supervisors into approving the project with a bait and switch tactic, sweetening the proposal to include a university that didn’t really exist.

“What is really driving the need to do this now?” Serna asked rhetorically during the January council meeting, adding that the proposed community for nearly 20,000 people was being built “in the middle of nowhere.”

But one person’s cow country is another person’s city. “We’re not in the middle of nowhere,” insists Rancho Cordova Mayor Linda Budge. “Characterizing it that way made it sound like Cordova Hills was out in the boonies. In reality, it’s across the street from Rancho Cordova’s city limits, and I don’t think downtown is the hub for all decision making in Sacramento County.”

Or at least its adjacent to land that Rancho Cordova wants to build on some day, acknowledges Matthew Baker, habitat director for the Environmental Council of Sacramento (ECOS), which filed a lawsuit in March along with the Sierra Club challenging the Supervisors’ approval. “But I’ve been on the site, and there’s nothing out there,” he adds, estimating that the proposed development along Grant Line Road is miles away from the core of Rancho Cordova’s urban development.

Beyond rebutting Serna’s characterization of Cordova Hills, Budge’s commentary could also be interpreted as a declaration of independence of sorts as the 10-year-old city of Rancho Cordova asserts itself, intent on charting its own destiny. “There are now three regional employment centers in this region,” (Rancho Cordova and Roseville in addition to downtown Sacramento) Budge says, emphasizing that each has its own needs and priorities.

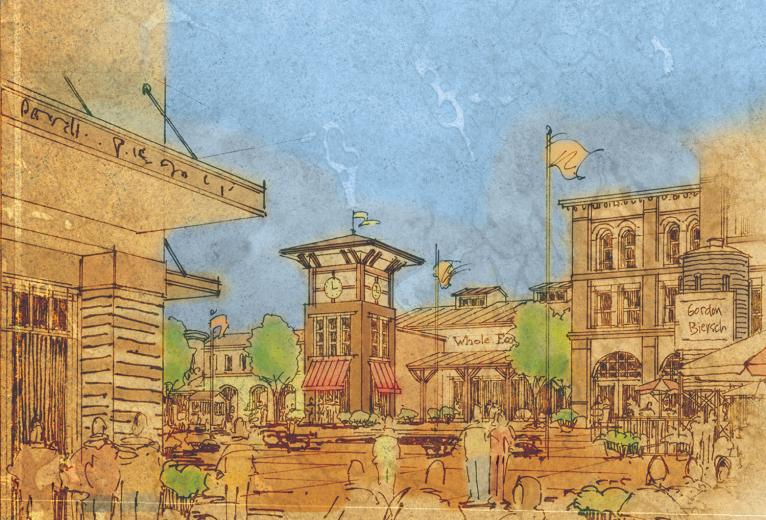

When Cordova Hills was proposed, the project looked like every other development plan in its embryonic stage. Areas for housing, schools, shopping, businesses, parks and open space were laid out on a map, each identified by its own colored splotch. Developer Ron Alvarado characterizes each splotch as a critical part of a self-contained community, with an advanced transportation system, land set aside for natural habitat, a mix of high- and low-density housing and 1.3 million square feet of commercial shopping.

“We expanded the preserves for natural habitat from 210 acres to 500 acres in direct response to environmentalists’ concerns,” says Alvarado, who added that one-third of the project’s acreage is devoted to parks and open space.

The maps also showed a university, a critical component in the tug of war between Alvarado and his critics because of the environmental benefits that it promises.

Urban planners, regulators, politicians and every local government agency worthy of an acronym weighed in topics from transportation and air quality to native plants during five years of review. They analyzed, evaluated, discussed and compromised as they stitched each colored splotch into what everyone hoped would be an acceptable plan.

Ultimately, this potential community for 30,000 people was unanimously approved by the Cordova and Cosumnes planning advisory councils and the Sacramento Planning Commission before getting the go-ahead from county supervisors. Budge, who has worked as an urban planner, believes that this deliberative approach leads to smart growth and well thought-out designs for cities.

The Rancho Cordova general plan was developed under the “blueprint principle,” a regional agreement designed to prevent urban sprawl by promoting development inside city limits. Budge argues the city has been true to that philosophy by adding zoning for retail, offices and places for people to work. The closure of Mather Air Force Base gave the city new freedom to design areas previously limited by flight patterns, safety zones and military use. New traffic patterns were created by extending streets that had been dead ends, providing options for walking, public transportation and commercial and residential use.

That planning has accommodated a growing population that works or lives in Rancho Cordova. Since 1970, its population has nearly doubled from 35,000 to 65,000. In addition, tens of thousands of people have found jobs in Rancho Cordova, as many Fortune 500 companies have located there. According to the city’s estimates, at least one-third of the people who work in Rancho Cordova, an estimated 17,000, commute every day from outlying areas.

Budge says that although the Cordova Hills development is not within her city’s limits, it is inside the Urban Services Boundary established by Sacramento County in 1993 and within Rancho Cordova’s formally recognized Sphere of Influence. “We didn’t formally comment on Cordova Hills because it was a county project,” she says, but the city’s planning department worked closely with developers.

“Ultimately, we are going to have to provide public works service to that area,” she says. The city’s engineering staff worked with the Cordova Hills designers to ensure that sewer, water and other necessary infrastructure was large enough for the expected demand, making the development plug-in ready at the appropriate time.

This was the first development under the county’s new general plan,” says developer Alvarado. “It was the first to be judged on specific environmental criteria instead of only where it was located.” As a result, “I think there were many people who didn’t think Cordova Hills was ever going to be built.”

“There is so much we need in Rancho Cordova.” Budge says, “And whatever you develop has to be part of a plan, and the No. 1 way any plan maintains compliance with air quality rules is to reduce vehicle miles travelled.”

She and Alvarado contend the way to do that is to set aside major land areas for large projects. More than 200 acres in the Cordova Hills plan was slated for a proposed university. Many critics suggest it was simply a ploy to make the development more attractive to decision makers.

Citing a Public Policy Institute of California report concluding that the state will fall one million college graduates short of job market needs by 2015, Alvarado contends the proposed university would fill an important academic need and prevent a brain drain of local talent. “It’s important to keep young people here,” he says. “Too often, when kids leave this area to go to college, they don’t come back.”

It would take years for a university to grow into full enrollment, and Alvarado says the site would be given back to the county if a university is not located there after 30 years. But the promise of a university played a more immediate role in gaining the project’s approval, too, because it plays so prominently into the development’s transportation plans.

Cordova Hills plans call for an internal bus system, neighborhood electric vehicles, bicycle lanes and shuttles to job centers and public transportation. Those measures would reduce the growth in smog-causing pollution by one-third, an element that persuaded approval from regional air quality officials.

A more critical measurement, however, would be the growth in carbon dioxide emissions that contribute to climate change as a result of increased population density. This increase challenges the project’s ability to meet regional standards for greenhouse gases and comply with new legislation that, for the first time, merges land-use and transportation planning in a “smart growth” strategy that creates sustainable communities.

In evaluating Cordova Hills, the Sacramento Area Council of Governments (SACOG) concluded that the development would hinder the region’s ability to meet greenhouse gas emission standards and that it would not be possible without the benefits attributed to the university.

“Many of the short or multi-modal trips from the project will turn into longer distance car trips if the university is not constructed early in the process or at all,” noted SACOG in a 2011 analysis.

The Sierra Club/ECOS lawsuit contends that county officials did not evaluate the worst-case scenario of the proposed 6,000-student university not being built, violating the California Environmental Quality Act. “Without the university, half of the claimed air-quality benefits are wiped out,” Baker says.

Critics were emboldened when the university pulled the plug. In a November 2011 letter to Alvarado, the small school with fewer than 100 students announced that “due to a series of global setbacks” it had decided to “cease operations at the end of the 2010-2011 school year.”

There are other contentious issues associated with Cordova Hills, too, including whether it would endanger the large number of vernal pools that dot the south county and allegations that the 1.3 million-square-foot commercial center is too large, attracting regional traffic instead of merely serving Cordova Hills residents.

But for now, Cordova Hills’ ability to build university classrooms may be the critical factor in whether those shops, houses, elementary schools and parks will be constructed. “They touted this as a green and self-contained community, but without the university, people are going to be driving all over the place,” Baker says. “The importance of the Sustainable Community strategy, which is intended to reduce vehicle miles travelled, can’t be understated.”

Cordova Hills is the first major development to be judged under those standards since the legislation was adopted last year. “It’s a test case, and that’s why people from all over the state are watching,” Baker says.

Alvarado, who as a board member for the Capitol Area Development Authority also advocates for infill projects in Sacramento, is undaunted by the criticism. “Some people think the university was just a Trojan horse to get the project approved,” he concedes. “But I still believe in the vision.”

He is continuing to consult with retired professors and education groups in an effort to land a university commitment for the site.

Furthermore, he adds, regional government planners have limited

ability to predict where people ultimately want to live. “The

real issue,” he says, “is how well growth is managed — wherever

it is.”

Recommended For You

Love Thy Neighbor

Sacramentans love infill development – until it actually happens

Infill development is promoted as an antidote to suburban sprawl and environmental degradation and is championed by city planners, environmentalists and policy makers of all persuasions. But as local developers Paul Petrovich and Phil Angelides have long known, infill leads to fights over allegations of increased traffic or environmental hazards.

Putting the Fab in Pre-Fab

Modular construction cuts construction and energy costs

The final stages of construction at a trend-setting apartment project in San Francisco’s SoMa neighborhood, known by its address at 38 Harriett St., largely resembled a life-sized game of Tetris.