The past few years have seen the biggest social upheaval against the banking industry in this nation’s history, and Capitol Hill lawmakers responded with 848 pages of legislation that liberal critics deride as weak and many conservatives call a job killer.

Although the ultimate impact won’t be known for several years, perhaps the most frightening critique of the 2010 Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act — commonly called Dodd-Frank after Democratic authors Sen. Christopher Dodd and Congressmen Barney Frank — is that the bill will perform its exact opposite function and set the stage for the next financial bubble.

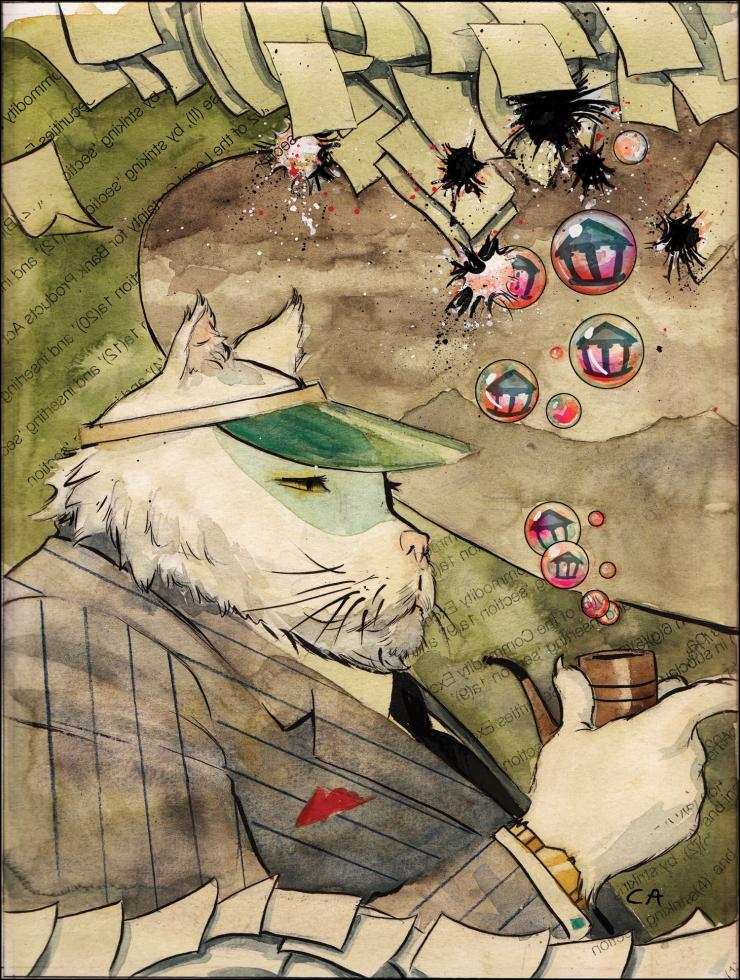

Financial historian Charles Geisst, author of “Wall Street: A History” and 17 other books on finance and economics, says he fears that community banks — looking to recoup costs from a blizzard of Dodd-Frank compliance paperwork — could become targets for big-time traders unloading harmful financial products.

“Watch out,” he says in an interview with Comstock’s. “Wall Street, to continue to do what it does, technically to innovate, needs an investing public who is receptive to this, and I think they’re going to find it. … The next time around, it’s going to be small institutions.”

As an example, Geisst says he can envision life insurance securitization becoming hazardous. If underwriting standards weaken, he says, terminally ill patients could bet on their own mortality as a way to bring cash to their families. Traders could then bundle up and sell those doomed securities to small banks for a quick buck. As the individuals died, the institutions would go down with them.

“If you start destroying credit worthiness — and to put it that way, life worthiness in the insurance business — then you’ve got a complete catastrophe on your hands,” says Geisst, a professor of finance at Manhattan College.

Local bankers interviewed for this article said they had no intention of taking on unwise risk. The 18 community banks in the Capital Region still have more than $300 million in nonperforming assets on their books, but bankers admit the austere Dodd-Frank act would squeeze margins and push bankers to search for new revenue.

“There definitely is revenue pressure because … we need to get lending going,” says Louise Walker, president and CEO of Dixon-based First Northern Bank.

Dodd-Frank aims to force banks to reduce leveraging, add visibility to the derivatives market, ban insider trading schemes, change the debit card fee structure and establish a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to guard consumers from fraud and other damaging practices.

Although leading Republican presidential candidates have called for a repeal, the law won’t be annulled unless the GOP wins the presidency plus the 60 necessary Senate votes.

Meanwhile, community bankers warn that Dodd-Frank could limit lending options while raising interest rates and other consumer fees. Although most of the provisions are directed at institutions with assets of $10 billion or more, small bankers worry about an indirect impact.

The primary concern voiced by local bankers is a provision in the law that aims to protect borrowers from unwarranted foreclosures. The provision calls for the newly established Consumer Finance Protection Bureau to create underwriting standards that meet a benchmark known as a ‘qualified mortgage.’ To earn that classification, bankers would need to document a borrower’s ability to repay a mortgage loan through a series of financial disclosures.

If a loan is not established as a qualified mortgage, than the borrower could block the foreclosure process following a default. And if federal regulators deem a banker’s documentation insufficient, the government could enforce severe penalties against them.

Considering that the U.S. foreclosure crisis damaged the financial health of the entire Western world, many bankers acknowledge that stricter rules around mortgage disclosures sound reasonable. Their concern is that the regulations as drafted would eliminate “character loans,” or loans that may not justify themselves on paper but are nonetheless given to citizens regarded as smart and trustworthy. Without the ability to make character loans, bankers say the bedrock art of lending is compromised.

“The regulators are a day late and a dollar short. Those in the private sector can figure out a way to get around regulators.”

Jonathan Lederer, president, Lederer Private Wealth Management

“Banking is a risk business. You cannot remove all the risk from banking and have a business that’s going to be able to help communities and help the economy. We take a risk every time we open the door,” says Thomas Meuser, chairman and CEO of Placerville-based El Dorado Savings Bank.

As an example, Meuser points to farmers. They typically don’t work standard, 40-hour-per-week jobs, and they can’t always validate a mortgage on numbers alone — but that shouldn’t disqualify them from receiving a loan, he says.

When discussing mortgage regulatory reform, it is important to note that violations on California property loans have been rampant in some areas. A recent audit of about 400 foreclosed homes by San Francisco County officials found nearly all of them contained some sort of impropriety, including failure to warn borrowers of default.

The audit shows 84 percent of the foreclosures appeared to be clear violations of law. Whether the proposal for qualified mortgages is smart regulation, California lending fraud has been overwhelmingly documented.

Still, many bankers fear Dodd-Frank would place unwarranted hardships on banks and consumers. “Instead of hiring customer service people, we will be hiring compliance people,” says Walker of First Northern Bank. “The more that’s added that we have to do, we’re not going to be offering as many products and services.”

Experts also predict the law will lead to widespread consolidation of small banks. Institutions that cannot afford new personnel may have to merge so a single compliance department can service numerous branches. This would create a new set of winners and losers within the industry.

“[Consolidation] gives a company like ours an incredible opportunity,” says David Taber, CEO of Sacramento-based American River Bankshares. “From a small-business perspective, it’s actually helpful because we as a company grow, have more mass, have more resources, and we’ll be able to do more for (businesses).”

He adds, “It may hinder consumer choices, however.”

While reviewing concerns about Dodd-Frank, keep in mind that virtually every component of the law is subject to change. Proposed regulations are now being passed between federal representatives and banks and other stakeholders with the goal of writing rules that are clear and attainable.

At the time of this writing, only 93 of the 400 rules have been finalized, and some observers predict the law might not be fully implemented for a decade. By the time Dodd-Frank is completed, some worry the finished product will be so punctured with loopholes that bankers will have little trouble evading the major provisions.

“The regulators, who often lack adequate resources, can sometimes be a day late and a dollar short. And there are those in the private sector who find ways to get around regulations,” says Jonathan Lederer, president of Lederer Private Wealth Management, an investment advisory firm.

“Bernie Madoff was a prime example,” he continues. “There were laws and regulations in place to protect investors. This guy was running a large Ponzi scheme, which a [U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission] review should have been able to uncover. And the regulators, even after being tipped five different times, still didn’t figure it out until it was too late.”

There also is the fact that for a skilled worker, more lucrative jobs exist on the other side of the government compliance desk. Experts acknowledged that federal regulators are understaffed and may not have the resources — or even the inclination — to properly execute the law.

“The Republicans have always had a strong argument — which usually lasts well into a crisis — and the argument is, you can’t regulate these institutions too strongly for fear of damaging them beyond the damage that they’ve already inflicted on themselves,” says Geisst, the financial historian. “Most of that is complete baloney … (but) a regulator who is not experienced is probably going to buy into that.”

In defense of the rule-writing process, banking representatives contend their institutional knowledge is essential to help the agencies employ laws that are enforceable.

“The California Bankers Association is in the advocacy business, and we will continue to talk with regulators about where things might be amended or rethought to make them more realistic, more practical, less burdensome but still effective,” says Rodney Brown, CEO of the association, which represents more than 200 lenders.

Whatever the result, recent news reports suggest the impending regulations have already led to less leveraging and risky behavior on Wall Street. Others argue Dodd-Frank might not prevent another financial crisis, but it lays a framework for criminal prosecution if bankers and traders engage in abusive practices.

But other observers believe these positive signs simply pinpoint the country’s current spot in a perpetual boom/bust cycle. And the root of the problem — the cycle itself — will not be fixed by Dodd-Frank.

Consider the primary factors that led to the 2008 financial crisis: Some experts contend the federal government engineered the crash through policies that encouraged and financed low-income people to purchase homes they couldn’t afford. The Dodd-Frank legislation does not attempt to reform government-controlled mortgage backers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

The counter argument is that deregulation in the 1990s and 2000s gave rise to the use of complex financial instruments that allowed big banks and traders to misrepresent toxic mortgage securities as safe investments and sell them to their own clients.

When pressed during 2010 Senate hearings that preceded the Dodd-Frank legislation, representatives for Goldman Sachs stood by this practice, but said they regretted the way it was documented in email. Time will tell if Dodd-Frank will rein in this aggressive form of trading.

According to Meuser, who after 43 years as a community banker has survived the bursting of several financial bubbles, the next step in a regulatory backlash is a broad recognition that the new rules hamper economic growth. Government officials typically respond by softening the regulations, he says.

“What ultimately happens is things start getting better, the economy starts growing again, and people start to say, ‘Oh, everything is fine now. … Let’s open it up.’ Some banks become overly optimistic. Financial institutions and borrowers take on too much risk, and then the economy blow up again,” says Meuser, who has served as a board member of the American Bankers Association and the California Bankers Association.

“I’m disappointed that we couldn’t have done something that would at least recognize that everybody wasn’t involved in this [crash],” he adds. “There was a meltdown on Wall Street, and it’s filtered down to Main Street. We’re all paying the price for the bad players. That’s what we always do. When is it going to end?”

Recommended For You

Banking on Business

Acuity with Rodney Brown

Since 2007, Rodney Brown, 65, has served as the president and CEO of the California Bankers Association, which represents the majority of banks doing business in California.

Merge or Purge

Community banks contemplate consolidation as regulatory costs grow

Banks throughout the country are putting new practices in place to comply with an onset of new federal regulations prompted by the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and other post-meltdown rule changes. Those expensive efforts are sparking major changes and concerns for some of the Capital Region’s smaller lenders.