A California initiative to allow more rent control appears to be failing overwhelmingly, despite the state’s exploding housing costs and ever-rising rents, and its sponsors are already talking about trying again in 2020.

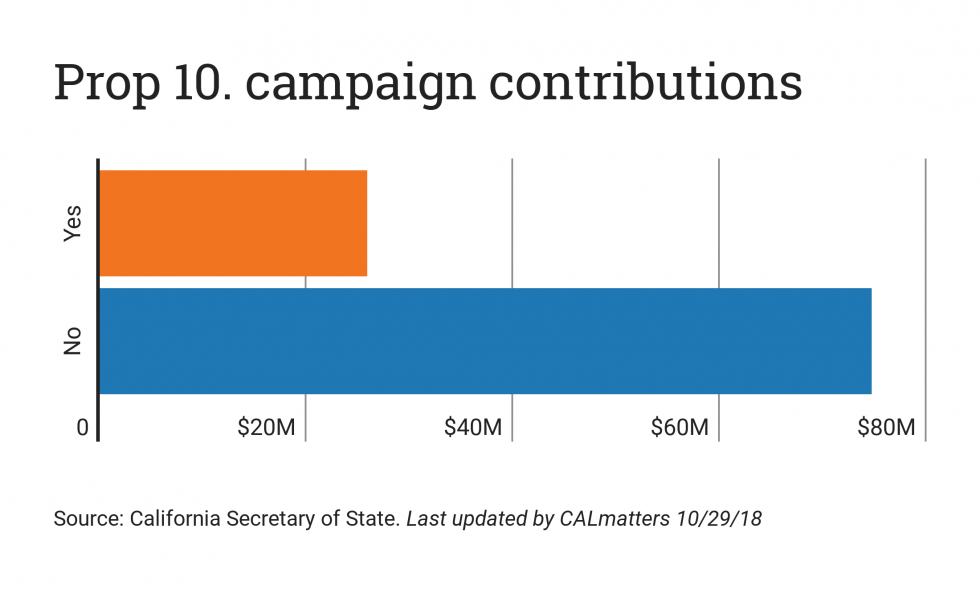

Tenant-rights groups and other backers of Prop. 10 always knew they had an uphill fight. Landlords, developers, realtors and a handful of Wall Street real estate investors have predictably poured tens of millions of dollars into defeating the measure. As of five days before the election, the No on 10 side had raised upward of $75 million and the Yes side, $26 million.

Backers of Prop. 10 point out the obvious: A disparity like that is hard to overcome.

“What the opposition has done with the money they’re using gouging renters is to confuse people,” said Damien Goodmon, director of the Yes on 10 campaign. “They can only win by using their money to confuse voters, and there’s a lot of confusion out there.”

The median price of a two-bedroom apartment in California has increased more than 20 percent over the past five years. A recent USC Dornsife/Los Angeles Times poll found that “lack of rent control” was the No. 1 reason people believed housing had become unaffordable.

“When you’re running a ‘yes’ campaign, you have the burden of proof to show both the problem and that the solution will help the problem,” said one veteran manager of initiative campaigns, who is unaffiliated with Prop. 10 but requested anonymity because of concerns over publicly criticizing professional colleagues at election time. “Here everyone already agreed on the problem, which is helpful for the Yes side.”

Here’s a further breakdown, including what lies ahead for the rent-control movement. It’s not all about the money.

Even if the “blue wave” turns into a blue tsunami, Prop. 10 is still in trouble

In some corners of the rent-control movement, supporters argue that the polls don’t consider the possibility of a “blue wave” bigger than predicted, one including many left-leaning renters or Democrats sympathetic to the cause. They say national polls weren’t accurate in the 2016 presidential election—why should we assume they’re right today?

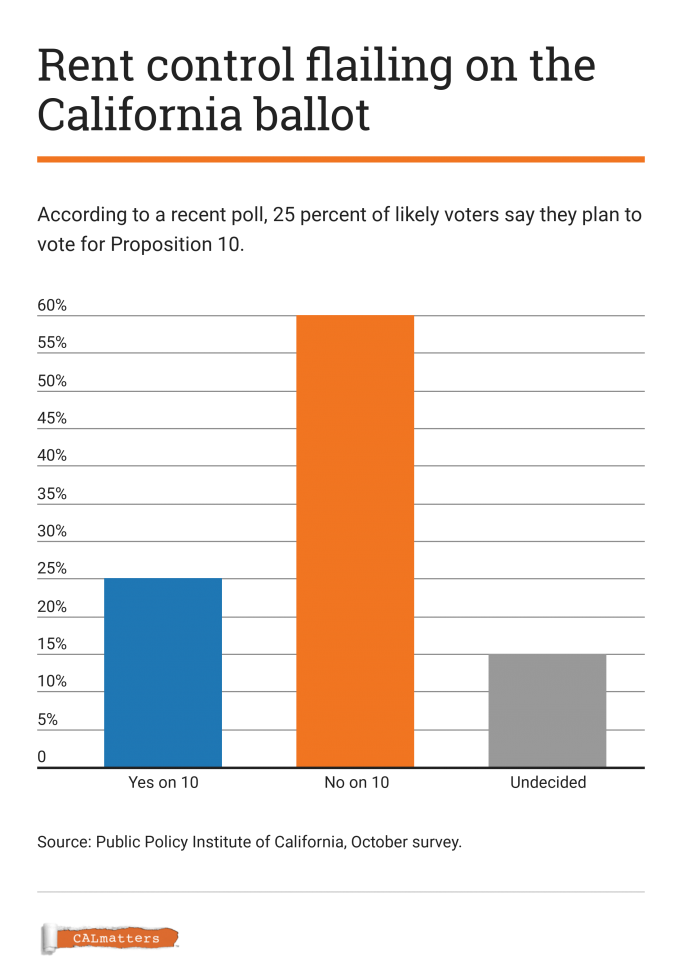

A recent poll by the Public Policy Institute of California, a nonprofit research organization, used a model for who is likely to vote that seems to tilt heavily against renters: About two-thirds of their sample is homeowners. But that’s roughly the same percentage of registered voters who are homeowners.

Public Policy Institute of California research associate Dean Bonner says he can’t remember any initiative polling as low as Prop. 10 this close to an election that actually ended up winning, even if the electorate looked wildly different from what was predicted.

Bonner says that if turnout looks like it did in 2016, a presidential election year in which California went overwhelmingly for a Democratic candidate, the Yes side could get more votes than predicted. But that would likely just trim the margin of defeat, not make Prop. 10 a winner.

Several other credible polling outlets also have the initiative trailing by double digits, with the brightest spot a Los Angeles Times/USC Dornsife poll with approval at 41 percent. Much of that polling preceded the avalanche of negative advertising that the No on 10 side unleashed.

Confusing ballot language

Prop. 10’s ballot title and summary apparently confuse voters.

The measure would repeal a state law called Costa-Hawkins, passed in 1995. That law bars local governments from expanding rent control in several ways: No rent control is allowed for units built after 1995, nor for single-family homes, and landlords have the right to raise rents after a tenant leaves.

The text on the ballot is complicated, and it invokes the prospect of state and local revenue losses of tens of millions of dollars a year. That’s actually not much in the grand scheme of things, but it sounds like a lot to the average voter.

“Because this repeals existing law and has the word repeal, there was a lot of confusion….Was this repealing rent control or was this actually rent control?” said Joe Trippi, a media consultant for Yes on 10 and a veteran of many high-profile campaigns.

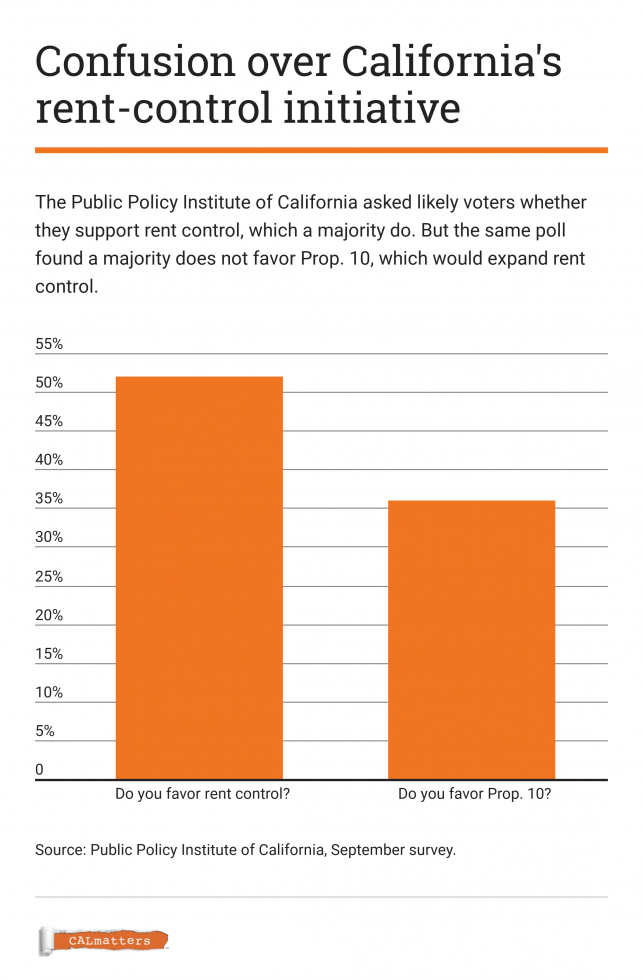

Indeed, a PPIC survey in September found that 52 percent of likely voters said rent control was a good thing, though only 36 percent planned to vote yes on Prop 10. That gap was even higher for surveyed renters: 67 percent liked rent control, but less than half favored Prop. 10.

And there’s uncertainty about what cities would be allowed to do if Prop. 10 passed. They could apply it to new construction, which would dilute the incentive to build more houses. They could conceivably apply it to single-family home rentals. The latter uncertainty has aided the No campaign, which targets homeowners with advertising about diminished property values.

The proposal is flawed in its lack of exemptions for such things as new buildings, said Steve Maviglio, spokesman for the No campaign. “Writing a blank-check initiative is always potentially bad because there’s a million holes you can poke in it.”

The wrong message?

On the other hand, allowing cities to do whatever they want with rent control comes with an attractive advantage: telling voters they can have more local control over housing policy.

The Yes on 10 campaign has emphasized the allure of local control, the human cost of the state’s housing crisis and Wall Street donations to the No side, anchoring its message in a “Rent is too damn high!” tag line.

But two words are conspicuously absent from most Prop. 10 advertisements: “rent control.” Although the phrase “limits on rent increases” is included in some ads, emphasizing “rent control” might have helped, especially with the concept of rent control outpolling Prop. 10.

Some strategists have said they would have featured the words “rent control” prominently. Trippi, who joined the Yes on 10 campaign over the summer, said he understood their criticism.

“I wouldn’t necessarily argue with that,” said Trippi. “Once we understood how badly we would be outspent, we made the decision that a lot of the messaging was going towards building a movement or coalition aimed at the housing crisis.”

Almost all the money from one organization

California pollsters and campaign consultants will tell you that if you want your initiative to pass, it better be polling high—at least in the high 50s—well before the election. That’s especially true if your opponent is going to outspend you.

A Public Policy Institute of California poll published in September found that only 36 percent of likely voters liked Prop. 10. That poll was conducted mostly before the avalanche of negative advertising began.

Those early poll numbers may help explain why the vast majority of the money on the Yes side has come from just one source.

The AIDS Healthcare Foundation has contributed roughly $21 million of the $26 million raised in support of Prop. 10. The nonprofit organization is headed by Michael Weinstein, a fiery and divisive Bernie Sanders-style progressive who has spent tens of millions on other state and local ballot initiatives in recent years.

Some powerful labor unions have chipped in on the Yes campaign and provided grassroots help, but few have thrown big money behind it. Amy Schur, state campaign director for the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment, a group pushing the measure, said some unions probably had to save resources for other causes on a busy ballot.

“We did hope we would raised more money,” Schur said.

The beginning of a stronger movement, or new leverage for landlords?

Backers of Prop. 10 say that even if the initiative loses, they’ve organized and strengthened a social movement that will continue to push the rent-control issue forward. And that might come as soon as 2020.

“If we’re not successful on Tuesday, legitimate conversations are going to take place around this state…about whether statewide rent control on the 2020 ballot is appropriate,” said the Yes side’s Goodmon.

But a loss on the magnitude of what the polls predict means landlords and their partners can say Californians have rejected an expansion of rent control in decisive fashion.

That’s powerful leverage for any future negotiations on the issue–negotiations that Democratic gubernatorial front-runner Gavin Newsom has pledged to facilitate if he’s elected governor.

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.