As California lawmakers struggled this week to address an apparent new normal of epic wildfires, there was an inescapable subtext: Climate change is going to be staggeringly expensive, and virtually every Californian is going to have to pay for it.

In the final week of August—just before the Legislature agreed to spend $200 million on tree clearance and let utilities pass on to their customers the multi-billion-dollar costs of just one year’s fire damage—the state released a sobering report detailing the broader costs Californians face as the planet grows warmer.

As horrendous as the wildfire situation is, the report made clear, it’s just one line item on a colossal ledger: It could soon cost us $200 million a year in increased energy bills to keep homes air conditioned, $3 billion from the effects of a long drought and $18 billion to replace buildings inundated by rising seas, just to cite a few projections. Not to mention the loss of life from killer heat waves, which could add more than 11,000 heat-related deaths a year by 2050 in California, and carry an estimated $50 billion annual price tag.

“Without adaptation, the economic impacts of climate change will be very costly,” warned the Climate Change Assessment report from Gov. Jerry Brown’s Office of Planning and Research, noting that the buildup of manmade greenhouse gases has already warmed California by up to 2 degrees since 1900. That bump, the assessment added, could rise to nearly 9 degrees by the century’s end.

And Californians are being hit with a double-whammy because fighting and preparing for climate change also costs money, and the Golden State has embraced an ambitious agenda to combat global warming. For example, Californians pay more for gas in part because of the state’s low-carbon fuel requirement and the cap-and-trade system that makes polluters pay for their greenhouse gas emissions.

“We are right now disproportionately bearing the brunt of both some of the impacts (of climate change) and trying to mitigate it ourselves,” said Solomon Hsiang, a professor at University of California, Berkeley who has researched the cost of climate change.

As that has sunk in, the reaction has been a mix of pragmatism, panic and political action.

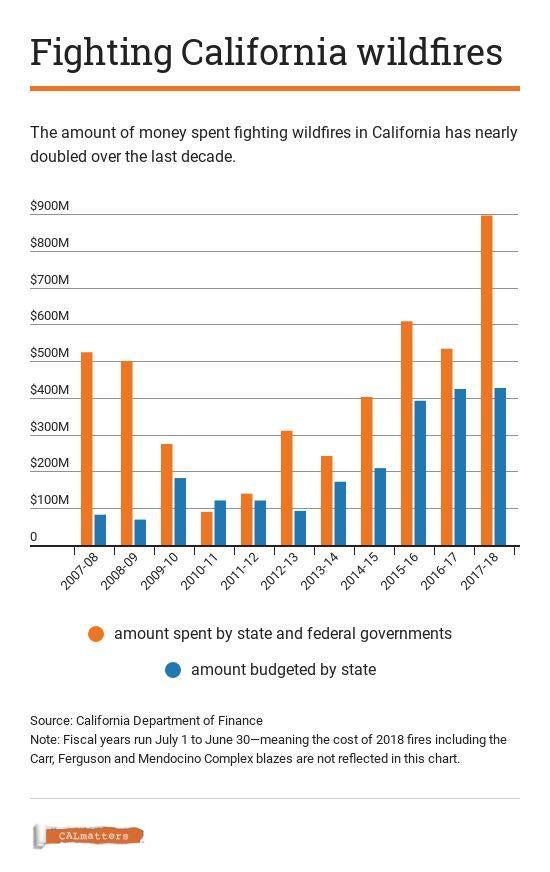

Earlier this month, as wildfires laid siege to the state and forced the evacuation of tens of thousands of Californians, Brown warned that “over a decade, there will be more fire, more destructive fire, more billions that will have to be spent on it, more adaptation and more prevention.”

At the time, California had blown through a quarter of the state’s $443 million emergency wildfire fund; in the devastating four and a half weeks since, the fund has been nearly wiped out.

“All that is the new normal we will have to face,” the governor said.

That realization swept through the Capitol again this week, as lawmakers approved a bill to require that all electricity in California come from renewable sources such as solar and wind by the end of 2045.

Senate Bill 100 was hailed as bold move away from climate-damaging fossil fuels—but legislative critics pointed out that California already has both the nation’s highest poverty rate and the highest per-kilowatt cost for electricity.

“I guarantee you: We pass this, and rates are going to go up,” Assembly Republican leader Brian Dahle said during a passionate floor debate.

“Californians cannot afford it.”

Sen. Kevin de León, the Los Angeles Democrat carrying the bill for 100 percent renewable electricity, dismissed cost concerns as nothing more than the rhetoric of naysayers “who try to undermine our clean-energy climate goals.” The cost of solar power has already dropped significantly and will likely continue to come down further, he said, in the years leading up to the 100 percent renewable requirement.

And, his supporters argued, there is also a cost to not fighting climate change—even more fires and floods than would otherwise occur.

Noel Perry, a founder of Next 10, a group that researches environmental and economic policy, says the benefits of California’s climate policies outweigh the costs because California can demonstrate to the rest of the world what’s possible to fight global warming while expanding the economy with clean technology investments. California’s economy, the world’s fifth-largest, has grown by 16 percent in the last decade while emissions fell by 11 percent, according to a new report from his group.

“In certain instances it will involve increased costs for some consumers and businesses. But because of how huge the climate change challenge is, we need to address it,” Perry said.

In some cases, the increased costs for fuel and electricity are more directly offset by efficiency standards for cars and appliances meant to help Californians consume less energy. For example, a recent mandate requiring solar panels on new homes in 2020 will likely add $10,000 to the price of a house, but could save homeowners more than $16,000 in energy bills.

In any event, climate costs are no longer abstract. Lawmakers have spent much of this year deep in the political nitty-gritty of who should pay how much for which climate-fueled disaster. The total cost of last year’s catastrophic wildfires still isn’t fully tallied, for example, but some estimates put it over $10 billion, and lawmakers have spent much of the year debating how much of that should be borne by taxpayers, utility companies or their industrial and residential ratepayers.

Under California’s liability law, utilities are liable for the damages from any fires sparked by their power lines, even if they weren’t negligent. Cal Fire alleges that Pacific Gas & Electric Co. equipment was involved in 16 of last year’s fires, and that in 11 of those, the company violated state codes that require keeping trees and shrubs away from power lines. The company says it met the state’s standards. Investigators have not yet determined the cause of the Tubbs Fire, the deadliest of last year’s blazes.

The utilities lobbied unsuccessfully this year to change the liability law. But they scored a partial win late Friday night as the Legislature OK’d a plan the wildfire committee advanced allowing utilities to issue bonds to cover damages from the 2017 fires and pass the cost onto their customers—even if the company is found negligent.

Senate Bill 901 would require a review of the companies’ finances before any surcharge is placed on ratepayers, and lawmakers supporting the plan said it would result in modest new charges—roughly $26 per year for residential ratepayers if the companies paid off $5 billion over 20 years. The alternative, they said, was the possibility that the company could go bankrupt, costing customers even more.

Consumer advocates blasted it as a “bailout” for PG&E; lobbyists for industries that use a lot of power said the plan would unfairly burden customers.

Meanwhile, the bill also calls for creation of a new Commission on Catastrophic Wildfire Cost and Recovery that would decide whether utilities can charge customers for fires in 2018 and beyond, and recommend potential changes to state law “that would ensure equitable distribution of costs among affected parties.”

Translation: Expect a lot more debate in the coming years over who will pay for damages from California disasters exacerbated by climate change.

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California’s policies and politics.