Donald Trump wants American companies to bring trillions of dollars in offshore cash back home, arguing that the money could be used to fund a manufacturing renaissance.

The president-elect has suggested that cutting taxes on companies’ accumulated offshore earnings from the current 35 percent to 10 percent would persuade them to repatriate that income; as the money returned, so would jobs.

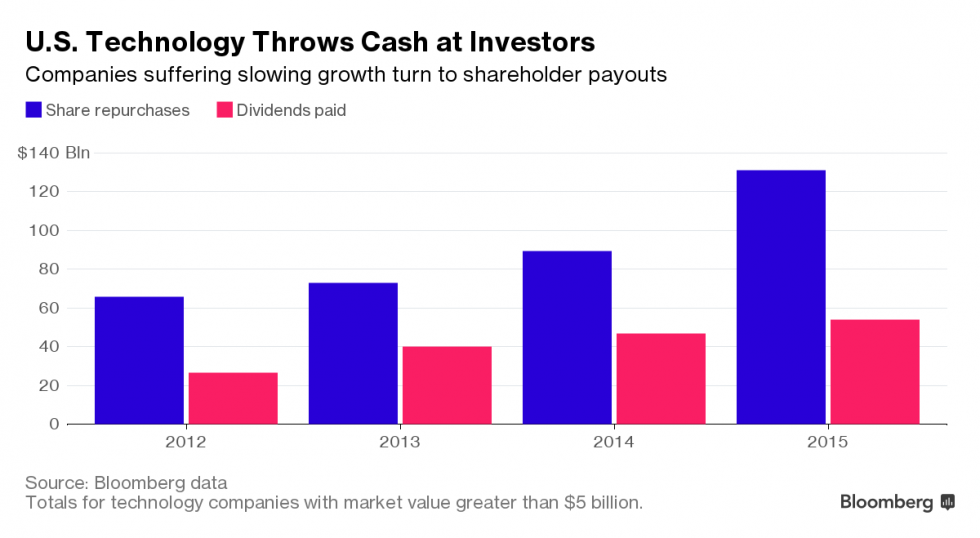

In fact, the capital is more likely to benefit investors than jobseekers. It’s not a shortage of funds that has held back job creation by U.S. companies. Apple, Microsoft, Pfizer and many others have raised huge amounts of cash — using low-interest debt — to buy back shares and boost dividends, not build new factories in the U.S.

Asked what he would do with repatriated cash should the Trump administration slash taxes on foreign profits, Cisco Systems CEO Chuck Robbins said in a phone interview last week: “We do have various scenarios in terms of what we’d do but you can assume we’ll focus on the obvious ones — buy-backs, dividends and M&A activities.” Gary Dickerson, CEO of chip equipment maker Applied Materials, says much the same.

Unlike other developed nations, the U.S. taxes corporate income globally, but it allows companies to defer paying tax on offshore earnings until they decide to repatriate that income. As a result, U.S. companies have avoided U.S. taxes by stashing roughly $2.6 trillion offshore, a figure cited by Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation. The top five in order of overseas cash holdings as of Sept. 30, are Apple ($216 billion), Microsoft ($111 billion), Cisco ($60 billion), Oracle ($51 billion) and Alphabet ($48 billion).

The new administration will “bring back trillions of dollars from American businesses that is now parked overseas,” Trump told the Detroit Economic Club as he laid out his economic plan in August. “This money will be re-invested in states like Michigan.” At a campaign rally in January, he said: “We’re going to get Apple to start building their damn computers and things in this country rather than other countries.”

Corporate America last enjoyed a so-called repatriation holiday in 2004, when the U.S. government temporarily reduced the rate to induce companies to bring foreign earnings home. What happened next is instructive. Though the legislation expressly forbade companies from using the cash to buy back shares, various academic studies later showed that more than 90 percent of the repatriated profit was used for buybacks, dividends and executive compensation.

This time around, Trump has talked about making a reduced repatriation tax mandatory. But it would still be almost impossible to force companies to invest the money in research or manufacturing, says Chuck Marr, director of federal tax policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a think tank founded by a former adviser to Democratic President Jimmy Carter. Doing so would spark a shareholder revolt.

Indeed, multiple companies have become increasingly reliant on buybacks to reward investors. Apple and Cisco, for example, have both made it a habit in their quarterly earnings calls to tout how much cash they’ve paid out. That isn’t about to stop any time soon because investors have come to expect such rewards.

Some industries are more likely to plow repatriated cash into M&A. Ethan Lovell, a portfolio manager at Janus Capital Group, says he expects pharmaceutical companies to go shopping. “The vast majority of companies that I speak with want to make acquisitions,” he says. “Their first order of business is build the business and enhance the growth rate.”

It’s also highly unlikely that companies with factories overseas will shift meaningful production to the U.S. After all, labor remains significantly cheaper in nations like China. Hourly compensation costs were $36.49 per employee in the U.S. in 2013, according to The Conference Board. The comparable cost in China was just $4.12 that year (the most recent figure), even after having increased more than six-fold over the preceding 10 years.

Besides, many companies that do still make products in the U.S. are automating production. Consider Intel Corp. The chipmaker has giant fabrication plants in Oregon, Arizona and New Mexico that employ just a handful of people to keep the machines running. Nothing the Trump administration does will stop robots from taking over large swathes of manufacturing in the long run.

Finally, many companies would rather put the money to work in markets where they generate most of their sales and growth. In an interview in San Francisco last week, General Electric CEO Jeffrey Immelt says he supports the Trump policy because it would boost GE’s competitiveness and flexibility and put his company on a similar tax footing as rivals like Siemens. But because GE generates more than half its revenues overseas, he says, “we have a lot of reinvestment opportunities outside the United States.”