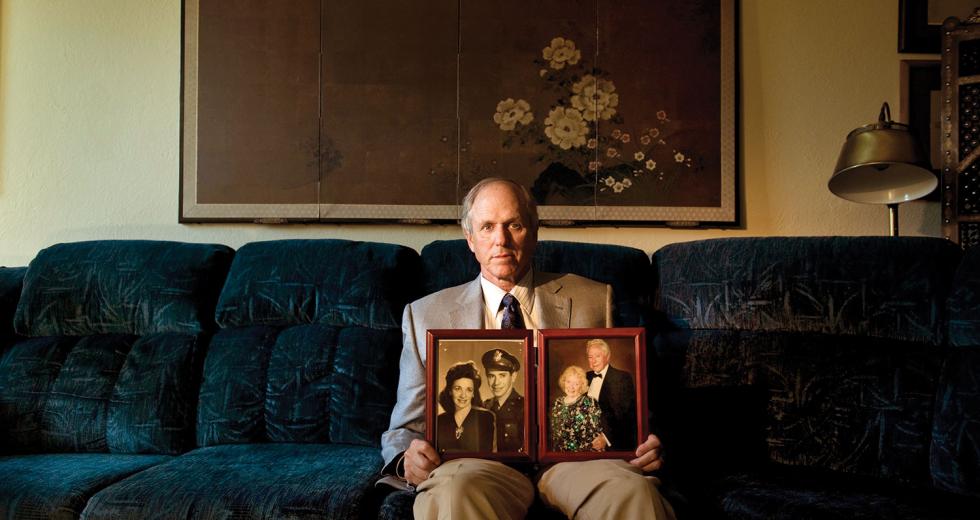

When Dr. Gerald Rogan’s mother was hospitalized after contracting an infection at an assisted-living facility, he learned firsthand that family advocacy is key.

After a discharge from the hospital, changes in his mother’s medication were not reconciled with the assisted-living facility. The hospital doctor prescribed an antibiotic to fight the infection, unaware Mrs. Rogan’s primary care physician already had her taking a different antibiotic. Following orders, the assisted-living staff gave her both.

“Nothing happened, but there was a greater toxicity risk in taking both,” says Gerald Rogan, a veteran emergency medicine physician who now works as a volunteer at Sacramento County Primary Care Clinic. “Discontinuing the other antibiotic wasn’t on her hospital discharge orders.”

Rogan stepped in as a son this time, calling both doctors to get his mother’s medication orders straight. Because assisted-living facility staff must follow written physician instructions, the orders had to be officially changed.

As the former director of Medicare Part B for both the California Medical Association and National Heritage Insurance Co., Rogan is familiar with the communication breakdowns that can occur during patient transitions. He advises families to be proactive, notifying the primary care doctor when a loved one is hospitalized and later ensuring a discharge summary is sent.

“The discharge summary will have why the patient was admitted, what the patient had, what was done at the hospital, what tests are pending and what the follow up should be,” Rogan says.

Although hospital doctors should (and do) communicate with primary care physicians, and discharge summaries should be automatically sent, the ball can be dropped. It’s also important that family members ask for a follow-up appointment with the primary care doctor within a few days of discharge.

Results of hospital tests must be reviewed and followed up, Rogan says. And the primary care doctor should be alerted to any medication changes, which should also be communicated to staff at an assisted-living or board-and-care home. Rogan suggests sitting down with staff (preferably a nurse) at the facility and reviewing the medication list.

Medication errors in inpatient and outpatient situations harm 1.5 million people each year in the United States, according to a report by the Institute of Medicine, the health division of the National Academy of Sciences. And more than 40 percent of inpatient medical errors happen during a transition, such as admission, transfer or discharge.

Medication mix-ups aren’t common, especially at Kaiser Permanente where an integrated computer system has been implemented, says Cheryl Haggerty, inpatient pharmacy supervisor at Kaiser Roseville Women and Children’s Center. Doctors at Kaiser are forced to reconcile medications through a discharge navigator when a patient is released, she says.

Errors can happen, though, when a patient transitions into a nursing home or assisted-living facility, Haggerty says. In cases where a patient is taking a therapeutically monitored medication such as lincomycin, in which blood is tested to determine levels, the facility might not continue testing. That results in taking incorrect levels of a drug, Haggerty adds.

“Any time you’re adding another level of care — a skilled-nursing home, assisted-living facility or home health care — there are a variety of layers, depending upon where they go, and a potential risk,” Haggerty says.

Recognizing that patient transitions can be improved, Sutter Medical Group’s goal is to call patients within two days of discharge to confirm medications and schedule a follow-up appointment with a primary care doctor within two weeks, says Dr. Monica Romo-Contreras, who specializes in geriatrics, family medicine and palliative care at Sutter Medical in Sacramento. In addition, Sutter has developed the Advanced Illness Management program to assist seriously ill patients with managing care.

“There are AIM liaisons in the hospitals, and they have a nurse that is opened up to the family to help with services and explain their medications,” Romo-Contreras says. “They also work with the family to deal with things at home that could cause the patient to go into the hospital.”

For example, a patient who experiences shortness of breath due to sclerosis of the liver can get help managing symptoms at home and identifying triggers. Most important, Romo-Contreras says, the patient and at least one family member have a good understanding of the illness and what questions to ask.

The Internet offers a plethora of medical websites in which to research an illness or disease, but not all online sources are reputable, Romo-Contreras says. Ask your doctor for recommended websites to research the illness and specific organizations that focus on cancer, Alzheimer’s or diabetes, for example.

Knowing the diagnosis of your illness, treatment options and the medications you’re taking is important in avoiding mistakes during a transition to another facility. Every person should keep a current list of medications in his or her wallet, says registered nurse Marji Wright, case manager for Mercy General Hospital in Sacramento.

“I practice what I preach,” Wright says. “In my wallet I keep a list of medications, allergies to medications, the surgeries I’ve had, any major medical illnesses and my primary care doctor and emergency contacts. I never bank on the fact that I’ll be able to tell someone.”

Wright says many patients don’t know the names of their medications but can only describe them as “the little round white pill.” In recent years, electronic medical records have made it easier to get a list of medications, but if you’re a Kaiser patient who has arrived by ambulance to Mercy General Hospital, they won’t have immediate access to your records.

Having a health advocate, someone who knows the ins and outs of your illness and also the medications you take, is a must for elderly patients, Romo-Contreras says. A designated family member or friend can help the person better navigate their health care and understand things more clearly.

For a seriously ill or elderly person, it’s best to assign a

health care agent, someone whom you trust to make legal decisions

for you when you’re unable, Rogan says. An advance health care

directive assigns an agent and then outlines the patient’s wishes

in different circumstances concerning life-sustaining treatments

such as breathing or feeding tubes.

The advance directive, which can be combined with a health care

power of attorney or drawn up separately, doesn’t give away

patients’ rights, but ensures they are followed.

“The patient isn’t turning their decision-making over to a family member,” Rogan says. “The patient is making the decision and then asking the family member to carry out those instructions in case they can’t.”

The next of kin has the right to make health care decisions for a patient who is unable, unless the person has already assigned a health care agent through an advance directive. It’s important to have an advance directive, especially if you want someone other than your closest family member to make decisions for you, or if you have no family. The California Medical Association provides information and a kit at cmanet.org.

California residents also have the option of filling out the physician’s orders for life-sustaining treatment form, or Polst. According to Romo-Contreras, the Polst form is universally recognized in California and usually can’t be refuted, even when an advance directive is challenged by a relative.

“The thing is, advance directives don’t cover every possible scenario, and that’s where the gray areas come in,” Romo-Contreras says. “You’re dealing with people’s lives and dealing with family members, so even if the advance directive says one thing, they could say another.”

A Polst is intended to complement an advance directive. Doctors should review the advance directive and Polst forms for consistency and update information if needed. The form is completed by a health care professional in accordance with the patient’s wishes and signed by a doctor. A health care agent designated in an advance health care directive is recognized in conjunction with a Polst.

As with all legal documents, you should make several copies of health care power of attorney, advance directives and Polst forms. Patients should keep a few copies for themselves and give a few to their chosen health care agent, other family members and their primary care doctor. In the event that a person is admitted to a hospital or nursing home, the documents should be taken to the facility.

At capolst.com, where Polst forms and information are available, it is suggested that seriously ill people post a copy of the Polst on their refrigerators for emergency medical technicians and firefighters to see.

Also commonly kept inside the refrigerator is a so-called vial of life, a plastic or glass container that holds a copy of the person’s legal documents for end of life decisions, their pertinent medical information and emergency contacts, Wright says.

Some fire departments have vile of life kits, or you can make one yourself in a jar. Label the jar, put it inside your refrigerator and then post a note on the outside to alert emergency personnel. Wright says emergency response people are trained to look for the vile and will transfer the information to hospital staff.

People often don’t like to think about illness and what might

happen, but planning ahead is important, Rogan says.

Rogan recalls when his dad, at age 88, fell while out with

friends. His father broke his neck, and a debate began about

whether his dad should go to a nursing home or get home health

care with visiting nurses. Rogan’s sister decided to keep her

father in her home and use home health care nurses, which are

covered by Medicare. But they needed more help.

“What many people don’t realize is that most of the cost comes out of pocket,” Rogan says. “Medicare pays for visiting nurses and physical therapy, but they don’t pay for home caregivers who support patients with the needs of daily living.”

Rogan’s father needed 24-hour care for about two months, resulting in high out-of-pocket costs and difficulty in coordinating care, he says. In a nursing home, all the care comes in one package, and some low-income patients may qualify for financial assistance from Medi-Cal to cover the significant portion Medicare doesn’t pay.

Later, when Dr. Rogan’s dad was affected by dementia and entered an assisted-living facility, he already had an advanced directive. So when his dad began having trouble swallowing food, Dr. Rogan could point to the advanced directive and make sure the doctor followed his wishes to not have a feeding tube inserted to sustain his life.

“That way, the family member doesn’t have to worry about feeling guilty,” Rogan says. “Or if family members have different opinions about what should be done, it’s the patient who has already made the decisions in writing.”

End-of-life decisions are difficult for everyone, but having a family plan and knowing the patient’s wishes makes things a bit easier. And for those who may only have only six months to live, hospice is a good option.

Hospice care is paid for by Medicare and can be provided at the hospital, assisted-living facility, nursing home or at the patient’s home. With hospice, patients are seriously ill and the family has agreed that they not be rehospitalized.

“There are a lot of misconceptions about hospice. It’s not the end,” Wright says. “You can go into hospice for three or six months and re-enroll later if you want or apply for an extension. It’s geared to make people as comfortable as possible.”

Hospice staff makes sure the patient has enough oxygen, sufficient pain medication and is as comfortable as possible, Rogan says. If the family knows their loved one won’t benefit from entering the hospital and no medical intervention is going to improve their quality of life, he says, then they should strongly consider hospice.

Transitions: Who

Cares?

Transitions:

Diagnosis Dilemma

Transitions: Folly

of Youth

Recommended For You

Family Values

Negotiating your personal worth as a caregiver

When Shelley Tabar’s father fell off her roof, she became his primary caregiver and subsequently lost nearly half her income.

Better With Age

Emerging trends offer senior living with style

Retirement communities are facing the challenges that come with catering to seniors in the 21st century. These consumers — and there are a lot of them — are demanding greater access to technology, life-long learning programs and attention to overall wellness.