Justin Bartosh spun a soccer trophy around on its head like a top, thinking about his upcoming novel. Justin had never written a novel before, nor had he read one in several years. But he enjoyed imagining himself as a famous novelist.

This novel would feature a 26-year-old man, like Justin, who lived in the inland California city of Safesto, also like Justin, but not with his parents, as Justin did. And the protagonist would certainly not work at Award It trophy retailers on Culligan Boulevard, because Justin hated his job. He didn’t know what the story would be about, but he knew it would be funny — like, extremely funny, and there would also be some action and some drama like a Quentin Tarantino movie. Maybe Tarantino would ask to turn Justin’s novel into a movie.

The trophy spun off the desk and clattered onto the ground. Justin sighed and withdrew his cell phone. No missed calls, texts, emails, posts, tweets, wikits, blogops, spoops or any other such notification. Nothing to do but lean down and retrieve the plastic ornament, which had dented, but that didn’t matter because it was only a display piece. Justin could replace it before Alfred returned from lunch, and the boss would never notice. Even if he did, even if Alfred asked Justin to explain the blemish in this particular pillar of recognition, there would be no repercussion, because the trophy was the kind that children received just for being on the team, whether or not they scored points or even showed up to practice. Participation trophies weighed about a quarter pound and probably cost the Chinese manufacturer 26 cents a piece.

Justin inspected the dent. There was something odd about the trophy’s weight, and when he shook it, water splashed inside. Was it water? He withdrew a key from his pocket and poked into the dent. After a few jabs, the key penetrated the surface and Justin used the key’s serrated edge to pry open the hole, which he knocked against his palm. Out fell four drops of an effervescent liquid.

The fluid had the consistency of olive oil and smelled like it too but was a shinier green. Justin swiped his tongue along his hand. A chemical taste, sweet but repulsive, like a coolant or cleaning solution. Low pulses started beating in his ears, and a steady thumping began in his head. The rhythm was tranquil and massaged his cranium from inside. Justin closed his eyes and a series of snapshots of his future began playing out like a filmstrip: There he was, holding an Oscar at the podium with Tarantino, and in the next slide he was walking down a red-carpeted hall of the White House with Barack Obama and then singing with the Red Hot Chili Peppers at the Coachella music festival.

In the front of the shop, the bell on the front door jingled as Alfred Stahl strolled in. At the sight of his only employee swaying in his seat with closed eyes, Alfred dashed to the desk and seized Justin by the shoulders. “How much did you have?” he yelled. “Did you touch the stuff? Taste it? What did you do?”

Justin turned to his boss and smiled. “It came out of the soccer ball. I put some on my tongue.” He smiled and extended his tongue.

“Listen to me, Justin. I know I don’t have your full attention, but you have got to focus. You may have just taken a lethal dose of a powerful psychoactive drug. Keep breathing!”

Justin took a deep breath. He felt soupy and warm all over, as if submerged to the floor of a hot tub. But he directed his attention outside of the tub. Beyond the water’s surface, there was a blurry figure raising his arms and yelling.

“Esteemerum!” cried the blob. “Justin, you have got to listen to me. Focus on breathing in and out. When you inhale Esteemerum in small doses, you get a small hit of self-worth. But if you swallow too much you can completely lose touch with reality. How much did you take?”

Justin lightly placed his palm on his bosses shoulder. “That doesn’t make sense, Alfred. It’s not a drug,” he slurred. “It’s a partish … ip … pashun trophy.”

Alfred stepped back, conscious of his own overreaction. There were no documented cases of death from Esteemerum, and he could tell the effects on his employee were already beginning to subside. He took another step back. For years Alfred had hidden the truth, decades even. Sometimes the secret made him angry, other times he felt ashamed. There were moments in the past when he nearly told Justin the true function of his job. The kid wasn’t ready to hear it — he never would be. But he deserved to know what was happening to him.

“It was a failed CIA experiment in the 1980s,” said Alfred soberly. “The federal government was convinced our soldiers lacked the self-reliance needed to overcome the Russians. So the feds manufactured a narcotic that would be administered into every child. The decision was made to hide a capsule of the stuff inside the one thing that we knew every kid would receive regardless of how they behaved — a trophy.”

“Whoooaa,” said Bartosh. Now he felt like a baby in the womb, surrendering to a gelatinous yolk of warmth and encouragement around him. But outside the membrane, he could sense something was awry.

“Don’t you see what I’m saying?” said Alfred, pulling up a stool. The green substance was still in front of them, spilled out on the countertop. “By inhaling a controlled amount of Esteemerum, you were all supposed to get a healthy dose of self-worth, but it didn’t work out that way. Instead of confident, you all just became,” he surrendered his palms to the ceiling, “obsessed with yourselves and your cell phones.”

Justin felt the claw of sobriety. The substance of the womb, that protoplasmic ooze of grandeur, drained out of him as his brain slowly coalesced around what his boss was saying. Justin had received participation trophies since the time he played tee ball at age six. This stuff, this Esteemerum, was what must have made him think his input would be highly valued at work. Perhaps it was also why he still lived with his parents. And why he couldn’t keep a girlfriend. And why he still made $9.75 an hour.

“I’ve heard people say that all my generation’s problems can be traced back to those trophies, but …” Justin shook his head. “I guess they were correct.”

“But if you knew it was hurting us, why did the government keep making the stuff, and why do you keep selling it?”

“Well, the truth is,” Alfred grinned, “you’re never too old to get something for nothing.” He rubbed a bit of Esteemerum on his gums. “You’ve heard critics say that Americans don’t make anything anymore,” he said, his finger still brushing his inner lip. “We make Esteemerum. The Chinese, they make our trophies and our cars and lawn chairs. But we have the confidence. We invented the stuff.” Alfred wiped his mouth clean and shot Justin another smile.

Justin couldn’t think of anything to say, so he pulled out his cell phone. No new messages.

Alfred pressed on. “You don’t remember the 80s, but you weren’t the only ones taking Esteemerum. We had some nights, man. Anyway, I probably shouldn’t even be telling you this. The important thing is that we wanted to give you kids the courage to follow your passions. What are you passionate about, Justin?”

“Well, I went to college to become a novelist, but I haven’t written more than a tweet since graduation.”

“Well then, let’s write your story. Hang on.” Alfred sucked another dip of Esteemerum off his finger. “I got a pen in here somewhere.” He stumbled to his office in the back.

The two men stayed in the shop that evening, discussing the novel and the certain fame it would bring both of them. Hours passed, the sky grew dark, but the boss and his employee were on a roll, jabbering, laughing and occasionally writing something down. When they tired, they cracked open another trophy. By the early morning, they had written half an Oscar acceptance speech, but nothing for the novel, which they decided would be a great novel, a riveting page-turner that pierced one of the most fundamental human truths … Justin just couldn’t think of what that was. Alfred assured him that he had personally penned thousands of novels over the years, in his own mind. Actually writing the words down couldn’t possibly be that hard.

Suddenly Justin had it. They could write about Esteemerum! That magical substance discovered by the people. And what was Esteemerum but passion — they had drained the contents of six trophies by now, but felt they no longer needed the stuff. Humans are born with the ability to create. To visualize. To actualize. To point one’s finger in the right direction and lead. To unite society as one, to tear down the walls of fear and … “Are you getting all this?” cried Justin.

“Yes! Yes! Keep talking!” Alfred was furiously scribbling notes.

Justin stood paralyzed in starry-eyed wonderment, an army of trophies surrounding him. “To strike down the walls of fear and … um … ”

It was getting early. The trophy shop would open again in just a few hours. The two men agreed to meet every night until the novel was complete. As Justin peddled home on his bicycle, he felt more aware of Culligan Boulevard: the dirty streets, the empty storefronts. But that wouldn’t last long. After his novel published, everyone in Safesto would read it and become inspired to fix all the city’s problems. Justin Bartosh had never felt more certain about anything. He checked his cell phone. There were no new messages.

Recommended For You

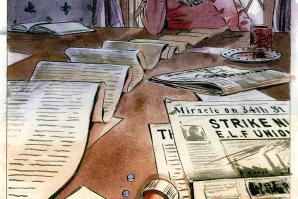

Polarized

Has the North Pole grown too complicated for Christmas?

The king stood over the toilet. The reluctant owner of that famous belly, that bowlful of jelly, lifted the overarching fold with two hands, exhaled, concentrated and waited for the stream to bolt from its alcove. No luck. Seconds passed, and a soreness grew in his knees.

Renaissance on Schedule

The new downtown arena is on track for a 2016 opening

Already embraced by business and city leaders as a catalyst that will ultimately launch a regional renaissance, Sacramento’s long sought and hotly debated entertainment and sports complex is finally taking shape.