NOV. 7, 2015

The morning air smells like burning wood.

It’s just after 5 a.m. on a Saturday. Yellow tape blocks off the area between 16th and 18th streets. Mike Heller is sitting by the train tracks on R Street, watching the century-old Crystal Ice and Storage building get burned alive with his dream inside.

No one died. But as fire crews battle the blaze, Heller thinks of his team and the time lost on this project: Two years, 89,000 square feet with 40 percent of tenants ready to move in, a vision for transforming the historic ice plant into an urban hotspot for retail and business — all shot to hell.

“I’m not Superman,” he would say later. “My emotions were raw. It took so much energy to get to where we were, to have it all blow up on us was so demoralizing.”

For weeks, Heller avoids the site. He doesn’t want to look at the ashes. He cancels meetings, and the team mourns in silence. The renewal project is not dead. Not even close. But finding the strength to start over is never easy. To get his mind right, the developer does what he was already planning to do: Heller takes a vacation.

AUGUST 1979

It’s not even 5 a.m., but Tim Fitzer is already feeling the heat.

He took over Crystal Ice three years earlier with no prior experience. This month, he’s supplying ice to the California State Fair for the first time. Without refrigerated rooms to store fruits, vegetables and flowers for the agriculture exhibit, the event requires Fitzer to work 19-hour days hauling 350-pound blocks to dump into boxcars at the fairgrounds.

“Seventeen days of hell,” recalls Fitzer, who would run the operation for 30 years.

In the 2000s, he called it quits after the plant became outdated. Now that he’s retired in Fair Oaks, Fitzer laments the loss of his old stomping grounds. He wishes he took more pictures of those grungy walls, ice machines and that 21-foot-long red and green neon sign with the words:

CRYSTAL ICE

COLD STORAGE CO.

Years later, Fitzer says he believed in Heller’s vision to transform the facility because he believes the abandoned structures would have been leveled otherwise. “A lot of those buildings would be going by the wayside if this wasn’t happening,” he says.

SUMMER 2005 – FALL 2013

It’s another hot season in Sacramento and developer Mark Friedman has a makeover on his mind. It’s 2005, and he just acquired the historic Crystal Ice plant and adjoining properties, and he thinks they would be perfect for a mix of retail, office and residential uses.

Related: While Looking Forward, Keep an Eye on the Past

For the next few years, he goes through a lengthy process of neighborhood outreach and architectural planning. Everything looks good. The receipt of entitlements come through in 2008.

“Just in time for the economic downturn,” Friedman says.

During the recession, Friedman struggles to raise the funds and support to develop the project. Years drift by. The plant just sits there, an old lime-green waste of space with vaulted interiors haunted by squatters and neglect. By 2013, Friedman is fully occupied working on the new Golden 1 Center and his bridge district in West Sacramento. He wants to sell the property.

But over lunch at Ettore’s European Bakery & Cafe, Heller proposes a resurrection of the run-down warehouse complex into something cool and vibrant, a modern village like Fourth Street in Berkeley or Portland’s Pearl District.

“I knew that the market was improving and that we would have a window to develop the property if we moved forward,” Friedman says, “so I turned to my trusted partner and close friend to handle the work.”

After a handshake agreement, Heller takes over development of the project, dubbed Ice Blocks.

MID-SEPTEMBER 2015

Everything’s on track. Designs have been submitted to the city. Permits will be here soon. The Ice Blocks project is moving full-steam ahead, just as Heller imagined when he pitched his dream to Friedman two years ago.

Heller’s design/build team did strategic demolition to save parts worth reusing: barn doors, reclaimed wood, metal ice chutes, boiler equipment. The idea was to reintegrate these old elements into a modern design.

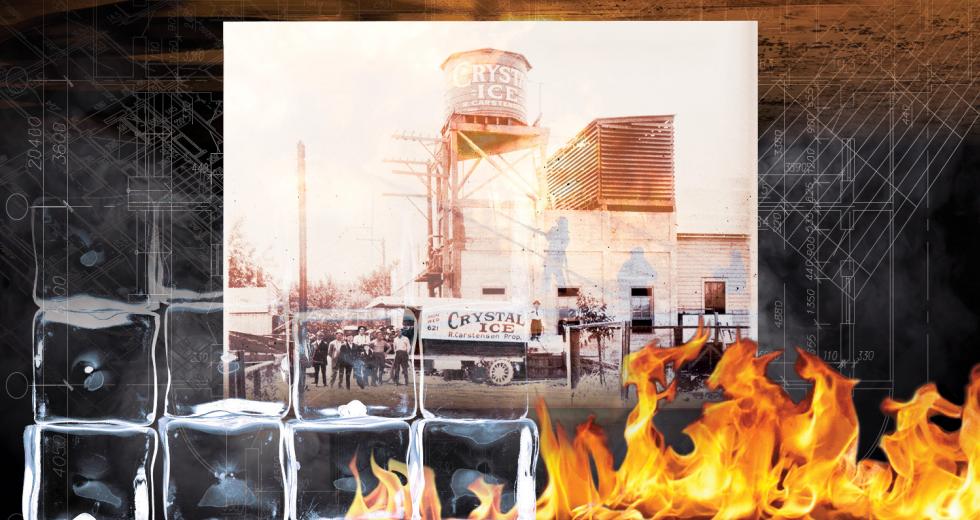

The century-old Crystal Ice and Storage building, Block 1 of

Heller’s project, was destroyed by fire last fall. (Courtesy of

Mike Heller)

The building dates back to the 1920s, when Model T’s used to pull up to the vending machine, when drivers paid pennies for blocks of ice to be carried on belts and dropped down the chute for pickups. For decades, this Crystal Ice plant was a notable fixture on R Street, a structure that stood like a stalwart historian witnessing the evolution of a gritty industrial corridor.

“The history was compelling,” Heller says, “and I wanted to fight to keep it.”

LATE DECEMBER 2015

Off Kohala Coast Beach on Hawaii’s Big Island, Heller is swimming with his wife and tossing his twin 5-year-old daughters into the waves. No phone calls. No meetings. The vacation and time with his family helps to restore the part of his spirit that got burned in November.

Between swimming and sleeping, Heller sketches crude drawings of buildings in a notebook. Refreshed, he emails his team to let them know new work will begin Jan.1.

He gives the team of about 12 a chance to back out. “We were all burned out and demoralized, so I wanted to give them an ‘out’ if the motivation simply wasn’t there,” Heller says. But the motivation is there. Nobody quits. Neither does the community. In the weeks after the fire, he receives hundreds of calls from friends, family, city officials, residents and restaurateurs. With all this support, Heller finds new energy.

Now all he needs is inspiration.

EARLY JANUARY 2016

The first week of the New Year, Heller and his team fly to Portland looking for a spark.

He has connections here in Rose City. He links up with business allies, architects, contractors and developers. They tour innovative buildings and brainstorm concepts. But to find his new idea, Heller must surrender the old one. The fire destroyed nearly everything. They did manage to save some quality wood beams, barn doors and boiler equipment, which he plans to use on one of the other blocks not destroyed by the fire. But Heller knows he can’t bring a demolished building back to life.

“My fear about the new realities of Block 1 is we lost something that is very special and soulful,” he says, “and I was worried that coming up with new construction might be disappointing and let people down, because new is oftentimes soulless and sterile.”

His fear subsides when he discovers the newest Northwest design craze: office buildings with heavy timber. They look more like mountain lodges than offices. Heller decides the unconventional design will be a perfect fit for the all-new Block 1, which will consist of offices for creative companies and retail stores on the ground floor.

“We were building within the envelope of these old, rickety buildings,” he says of the original plan. “Now without those handcuffs, we’ve got a big canvas to paint and we can paint however we want. We’re in a much more liberating place of making this project better.”

Back in Sacramento, Heller puts the team on a tight deadline. He feels pressure to fast-track the project, get the planning application to the city and win back those previously committed tenants while interest rates are low.

Everything seems to be in order, but then Steve Guest, principal architect of RMW architecture and interiors, shows early renderings. Heller likes the interior, but he feels the exterior isn’t capturing the industrial vibe of the area. Enough panic sets in for Heller to freeze the project for 30 days until the design is right.

“It wasn’t coming together for me,” he says, “and if I’m not feeling it, I can’t commit, so we did a timeout.”

MARCH 2016

Guest calls Heller the type of guy who “essentially knows what the right moves are, but he can’t see them until you show them.” They worked together on the MARRS project (Midtown Art Retail Restaurant Scene), converting an old Bekins Moving and Storage building on 20th and J streets into a popular midtown hub.

They planned Ice Blocks to be a bigger version of that. They hoped to recast the old barn doors as the suite entrances and reposition the old ice chutes into the lobby design. They wanted to use the bones of the building to bring out its essential character, but most of those bones turned to ashes. Guest has never been through a fire before this one.

New plans for Block 1 include roughly 100,000 square feet of

office space, 40,000 square feet of retail and restaurants, and

106 underground parking spots. (Courtesy of Heller Pacific)

After three different drafts, Guest finds the right mix of old and new. The revised plan features one level of underground parking and a recreation of the loading dock platform from the historic building. This dock will be deck space, elevated 2.5 to 3 feet off the ground, wrapping around the building to form a raised pedestrian plaza.

In place of the old plant, the new design features two buildings, each with a footprint of 17,000-square-feet and four stories tall, connected by a sky bridge. The outside will be mostly glass. The inside will be Douglas fir glued-laminated timber or concrete, with restaurants and shops on the first floor, and office and retail space on the second. The top two floors will have space that can be divided into office suites and office lofts on the fourth floor.

Heller wanted the wood frame to be exposed on the outside, but timber deteriorates quickly in the Capital Region’s hot and dry climate. So instead, they will attach raw steel on the outside to the wood frame, which will still be visible because the building is transparent.

Heavy timber works well as a framing solution, achieving a burn rate on par with steel without the need for fireproof coatings, Guest says. Also, the whole building will have sprinklers.

MAY 2016

The project is now called Ice Rally Cap. The name comes from baseball, when bench players or fans invert their caps late in a game to spur a team to a last-second comeback win. Seems fitting, Heller says. He lost all of his tenants except the anchor, Republic FC. But despite the setbacks, Block 1 is set be out of the ground by the fall and completed by the end of 2017.

It’s been half a year since the three-alarm fire gutted the abandoned ice plant. The cause of the fire is still unknown. The high heat and collapse of the building made it nearly impossible to gather evidence, according to the Sacramento Fire Department.

Nobody has forgotten the devastating loss, but from the rubble Heller and his team found a way to build even more momentum.

“I think R Street is such a great narrative, because it’s like one project has led to another project and on and on,” says Wendy Saunders, executive director of the Capitol Area Development Authority. “Warehouse Artist Lofts was critical in sparking the whole thing. Mike’s project is similarly going to have such a catalyzing effect on the whole neighborhood.”

South of the project, CADA recently purchased property that will be mixed-income housing.

Looking back now, Heller sees the fire as a once-in-a-lifetime moment that allowed him and his team to rise up in the face of tragedy.

“It was neat to see how my team responded to create something everybody’s fired up about,” he says. “I think we’ll look back and there won’t be any sadness about what we didn’t do, because we’ll have a really strong, iconic Ice Block 1.”