Five hundred miles south of Sacramento, 36-year-old Luca Carmignani runs the California Fire Science Consortium lab at San Diego State University. Carmignani is a lean, bearded man, originally from Tuscany, Italy, with a passion for studying how fire works.

Along with his students in the small lab, crammed with computer terminals, shelves stacked with experimental building materials in different shapes and sizes, as well as a small wind tunnel, he runs flammability experiments, seeking to find out which sorts of vegetation are more vulnerable and which are less vulnerable to flames, what kinds of glass are flame retardant and what angles and thickness are best to build at to maximize a building’s fire resistance.

He has found that flames jump sharp angles quicker than they do softer angles. His lab also operates infrared cameras to measure how hot flames have to get before these various materials will alight. Over the coming years, their findings will influence how builders and landscapers work, what materials they use and what homes and gardens look like, throughout California and beyond.

Carmignani has been working with fire for years. Now, in the wake of this year’s devastating firestorms in Los Angeles, he thinks that California is on the cusp of huge changes in how cities are developed and what obligations property owners and residents will have to harden their homes and businesses against the spread of fire.

“Preparedness is the key,” he says, and that means that newer homes will have to be built to ever-stricter building standards, and older homes will have to be retrofitted with, among other things, new vents and fences.

In other words, what cities look like, how space is used, what building materials are used — all of that will change in the near future.

When the Altadena and Palisades neighborhoods of Los Angeles were obliterated by firestorms in January, builders, insurers, fire specialists and politicians around the state sat up and took note. In an era of escalating fire disasters, with insurers fleeing large parts of the state and with builders desperate to find ways to construct houses that would better resist the flames, what can we do to defend our neighborhoods?

Los Angeles set up a Blue Ribbon Commission, in conjunction with UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs, to investigate the fires and develop policies for rebuilding communities that are more fire-resistant, both through utilizing new building materials and also through improving infrastructure — moving utilities underground, making power grids safer and making improvements in water storage facilities.

At the state level, Gov. Gavin Newsom convened a number of groups to look at the reasons the fires were so devastating and to plan ways forward. In February, he also issued an executive order mandating a speedy update of the state’s Fire Hazard Severity Zone mapping — an important update, since those maps are used by local fire districts to plan firefighting strategies and to mandate fire mitigation measures.

Although Sacramento has so far been spared the conflagrations that have, over the past couple decades, devastated large parts of Los Angeles, San Diego, Santa Rosa, Berkeley, Oakland and other urban centers, as well as smaller communities such as Paradise, nobody’s taking this run of good luck for granted. Instead, there is a full-court effort underway to shore up defenses while there is still time.

Newly created building materials, such as insulated concrete forms, or ICFs, are increasingly being used on building interiors to serve as a fire retardant. And many builders are starting to embrace the notion of 3D printed homes with concrete interiors. What these homes might lack in character, they will make up for in safety.

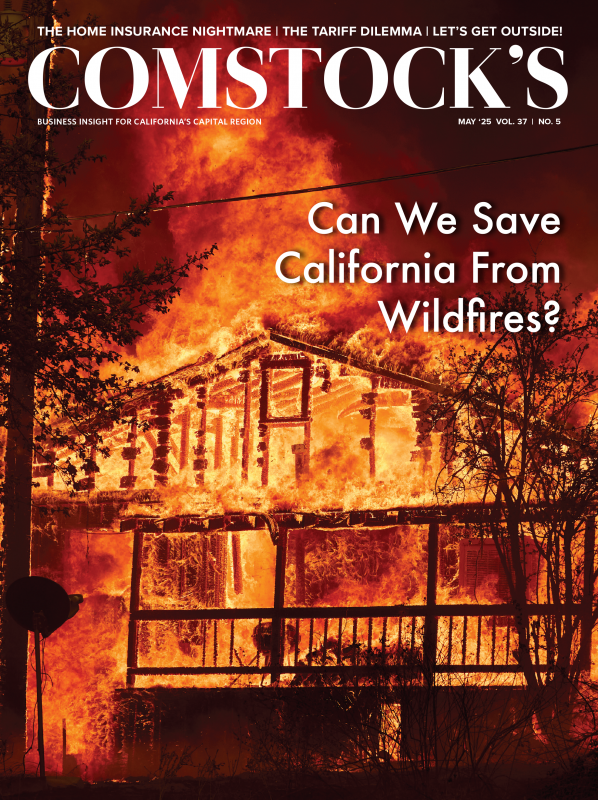

At the California Fire Science Consortium lab at San Diego State

University, researchers are studying how to fireproof a home.

Fire investigators found that more than 90 percent of the LA

homes that burned didn’t have fine enough meshes in their roof

vents to prevent smoldering embers from entering homes. (Graphic

by Luca Carmignani)

“It’s about a system-based approach to resilience,” says Steve Hawks, recently retired from a job with California’s Office of the State Fire Marshal, where he worked on overseeing fire mitigation community programs. Hawks is now working as the senior director for wildfire at the South Carolina-based Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety. Sacramento, he says, needs to do “wildfire mitigation at the community level. A big portion is individual property owners implementing risk mitigation by retrofitting homes. And when you build a new home, we recommend wildfire preparedness.”

In early March, the IBHS released a preliminary report on the Los Angeles fires. Among its findings was that more than 90 percent of the impacted homes had vents that didn’t use fine enough metal meshes (less than 1/8 of an inch in diameter) to stop smoldering embers from getting into the interior of the buildings through the venting systems and setting those interiors ablaze.

Most of the homes that burned also had wooden fences within 5 feet of the exterior of the home, making it far more likely that those dwellings would catch fire in the event of a major conflagration. The researchers also found that the risk of an uncontrollable fire spreading in an urban neighborhood was higher when the buildings were within 10 feet of each other, even when those buildings were constructed with fire resistant materials.

Like other California cities, Sacramento employs defensible space inspectors to check properties and make sure there aren’t flammable items stored near the exteriors of homes. While the city prefers to offer incentives — such as access to retrofitting grants — to clean up these areas, ultimately, Hawks says, inspectors have the power to issue fines if their requests are ignored over a period of time.

Now, with new building codes coming online, the system of carrots and sticks is about to be stress-tested to see if it can handle increased retrofitting and defensible space requirements — and, in all likelihood, pushback from some residents who don’t see why they should have to modify their homes and clean up their yards.

Sacramento’s efforts to protect itself from fires have been given two regulatory boosts by the state in recent years. In 2008, Chapter 7A of the building code was put in place to ensure that new homes were built with fire-resistant vents, double (and even triple) paned windows, defensible spaces around their exteriors, fire resistant siding and non-combustible roofing. As a result, says Chris Ochoa, senior counsel for codes, regulatory and legislative affairs at the Sacramento-based California Building Industry Association, most of the homes built in the past 15 years have been significantly hardened against fires.

Newly built homes and communities in California now have wider

streets to allow fire trucks to get in and for residents to

evacuate, says Chris Ochoa, senior counsel for codes, regulatory

and legislative affairs at the Sacramento-based California

Building Industry Association. He’s standing in the Tri Pointe

Homes development in El Dorado Hills. (Photo by Fred Greaves)

So, too, have more recently built master-planned communities that include wider streets to make it easier for fire trucks to get in and for residents to evacuate, as well as spacious thoroughfares built on the communities’ periphery that serve as fire breaks. Think of them as modern-day moats, designed not to protect against aggressive armies but to provide at least some protection from climate change-exacerbated fires.

The second boost is the likely adoption of a so-called Zone Zero statute that would require particularly rigorous fireproofing of the area from zero to 5 feet of a building’s exterior. In high-risk zones, this would involve clearing that space of all combustible vegetation and replacing lawns that border on the homes’ edges with stones or patios. It would mandate fencing and siding be built with non-flammable materials; and it would require residents to keep that zone free of potentially combustible clutter.

“There’s a lot in play already, either about to come online or that has come online,” says Yana Valachovic, forest advisor and county director for Humboldt and Del Norte at the UC Cooperative Extension.

Because of the requirement for public input and debate, the new Zone Zero code hasn’t been implemented. Now, in the wake of the fires, Gov. Newsom has ordered the process be sped up. Ochoa believes it will become part of the code in late 2025 and will start being enforced a few months later.

Zone Zero will result in developers having to pay far more attention to “defensible space” when building homes, landscaping communities and so on. It will, in consequence, change the visual contours of the city, altering the composition of gardens and perhaps banishing the classic wooden picket fence to the history books. In new developments, streets will be wider — much as European cities, such as Paris, moved towards wide boulevards as part of an effort to prevent urban fires during periods of reconstruction in the 19th century. In older neighborhoods, more homes will be retrofitted.

There will be, says Frank Frievalt, director of the Wildland-Urban Interface Fire Institute at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, “a mitigation policy focus” so as to modernize, at scale, homes and businesses in edge areas around the state where wildlands and urban centers meet. For Frievalt, it isn’t just a matter of stopping individual fires from spreading; it’s also about economic survival.

Without this effort, he argues, eventually cities will find it harder and harder to raise bond revenues — since those bonds are serviced through revenues raised by the collection of property taxes; and if fires render whole communities uninsurable, ultimately potential owners’ ability to access mortgages will face growing headwinds, property values will fall and property taxes will, in consequence, crater.

When a wildfire strikes anywhere in the state, mutual aid is

called in, meaning available firefighters from other agencies

assist other communities battling a blaze. Here, Auburn

firefighters assisted in a Northern California wildfire. (Photo

courtesy of Cal Fire)

In some ways, Frievalt says, the situation is dire enough, with enough interconnected parts all at risk of failure, that it resembles the start of the financial crisis in 2007-08. In other words, remediation is not optional; it’s a matter of fiscal urgency for cities up and down the state. “If you can’t mitigate the risk,” he argues, “then the whole concept of lending is in jeopardy.”

That’s why, Frievalt explains, cities in the Capital Region, including Sacramento and Elk Grove, are now crafting ordinances to ensure the rapid build-up of defensible spaces and mandate the use of evermore fire-resistant building materials. It’s why wildland-urban interfaces in the Sierra Nevada foothills are being re-landscaped to mitigate heat transfer and limit how fast flames can spread from the hills into urban neighborhoods.

It’s also why California legislators recently passed AB 38, a requirement that home sellers file a home hardening disclosure form, explaining what, if anything, has been done to harden the home against fires. This, forest advisor Valachovic explains, will provide an incentive to home sellers to boost their defensible spaces and retrofit their homes so as to make their property more attractive to potential buyers. Federally, California congressional members — both Democratic and Republican — have been pushing for legislation to provide tax credits for homeowners’ retrofitting expenses. There are also, she says, ongoing conversations about how to modify transit systems and land-use priorities, to make infrastructure less vulnerable to fires.

“We have a lot of infrastructure already to be thinking of,” Valachovic says. “It’s going to be a layered approach. It’s a lot to take on, but we shouldn’t be deer in the headlights. We need to be thoughtful and turn many dials simultaneously.”

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Is Sacramento Ready for the Big One?

Levees and dams are being repaired and expanded to prepare for a future flood

Climate change is increasing the strength of Sacramento’s winter storms. Higher temperatures allow atmospheric rivers to carry more water, research shows. Climate change is also jacking up other flood risks, such as sea rise and snowmelt. All this is raising the chances of catastrophic flooding in Sacramento.

Some Burning Questions on Wildfires

FROM THE PUBLISHER: As it is with all catastrophes, there’s plenty of blame to go around. I guess this can be a useful exercise at some point, but it won’t rebuild people’s homes, restore their most valued possessions or, most importantly, stop this from becoming an annual, recurring heartbreak. We need to ask and answer some obvious questions.

Why California Keeps Putting Homes Where Fires Burn

CalMatters: To many ecologists, economists and other experts on California wildfire risk, the vow to rebuild is part of a familiar California cycle as predictable as the Santa Anas: We keep putting homes in the path of the flames.

LA Fires Could Drastically Drive Up Insurance Premiums — and Test California’s New Market Rules

CalMatters: The deadly and destructive fires in Los Angeles — which some say could be the costliest in the state’s history — will further strain the insurance market and worsen the financial position of California’s insurer of last resort.