The bald eagle is perched high in a pine tree, sharply surveying Lake Natoma below. Once he spots his prey, he thrusts his 7-foot wings back and spreads them wide, soaring in a rapid downward descent. Silently, he swoops into the water, plucking out a startled trout from behind with his sharp talons. The eagle crosses the lake and ascends, carefully maneuvering through trees and branches until he plops the still-squirming trout into a huge nest, another meal delivered to a pair of hungry, screeching eaglets.

The flight of a raptor is a beautiful thing to behold. It’s been captured in photos, videos and art, described in literature and even song. Whether it’s an eagle, hawk or an owl, we watch in wonder at the way the bird is able to navigate its big body and wings through difficult spaces. Now, an exciting new project at UC Davis is studying these raptor flight patterns in partnership with the U.S. Department of Defense to learn how bird flight can help develop the next generation of unmanned aircraft.

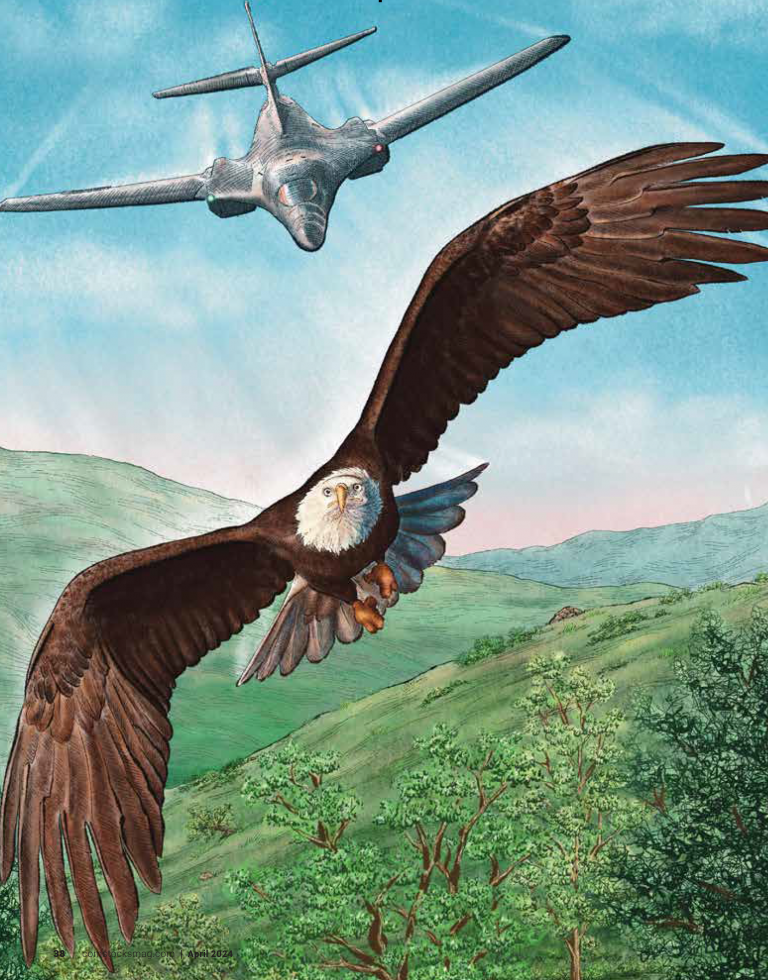

(Illustration by Mariah Quintanilla)

With a $3 million grant from the Defense Department, UC Davis is establishing a bird flight research center and beginning construction of a flight hall on the grounds of the California Raptor Center, located on the university’s south side, in the fall. The new center will utilize motion capture and photogrammetry — which uses photography to determine the distance between objects — to image birds in flight and create 3D models of the wing shapes that will help design uncrewed aerial systems, or UAS. The center will be the first of its kind in the country.

Researchers will use some of the raptors living at the center — including a great horned owl, red-tailed hawk and sibling turkey vultures — to capture their motion. These birds were either injured in the wild or, in some cases, kept as domestic pets. Healthy birds trained by falconers will also be used. The researchers hope to learn how different types of birds maneuver around complex environments to help develop surveillance drones and other unmanned systems to deliver packages, detect and fight wildfires, and more.

“This is just a great location for this kind of thing to happen, because the Central Valley of California has one of the highest abundances and densities and diversities of different raptor species, especially in the wintertime when a lot of different species move through the area. So it’s very fitting that there should be a raptor center here as part of UC Davis,” says Julie Cotton, co-manager of operations at the center, which is also home to a bald eagle.

The flight hall was the brainchild of Christina Harvey, an assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering who started at UC Davis in 2022. She came to the university because she wanted to work with raptors and bird experts. She also had experience in getting grants from the military for research.

“Our role is to identify the most beneficial attributes of the way animals fly. And then with that information, the Army can develop enhanced ability to do things like surveillance,” says Harvey. “They can also do some low Earth maneuvering, where you can weave in between complex forests. And this type of technology is also going to be very important for things like firefighting.”

She took her idea to Michelle Hawkins, a professor at the renowned School of Veterinary Medicine and director of the California Raptor Center, who was excited by the thought of a raptor research center at UC Davis. “Several flaps, for example, can potentially give us what we need if we are able to do that a few times,” Hawkins says of the research. She is also consulting with falconry experts and using their birds in the experiments.

“We do have some equations of how a bird flies depending upon what species that bird is. Some are more gliders, some hover, some dive,” says Hawkins.

The majesty of flight

It’s twilight on the bluffs of Lake Natoma, the perfect time for a raptor to be hunting prey. You hear a swoosh, like a whisper, pass by and see a majestic, almost mystical creature with ghostly white wings gliding beneath the low-hanging branches of the trees, scanning the ground for an errant mouse or mole. Back and forth it goes, in a zig-zag, rhythmic form between the trees, before it disappears silently into the night.

Bald eagles typically weigh between 8 and 14 pounds and can carry

one third of their body weight, such as a 3-pound trout. Their

large wingspan also allows them to fly with large objects like

long branches for building their nests.

How do you capture the skill of a raptor in flight to create a human-made aircraft? Bird flight has been studied since ancient times, but there are still unknowns. Remember when Jeff Bezos said back in 2013 that Amazon would one day be delivering packages by drones? Well, they’re still working on the technology. So many factors can affect drone deliveries, from tall buildings to wind gusts and unexpected drafts. That’s where the raptors come in. Their ability to maneuver in different, challenging spaces is something the Defense Department is very much interested in.

The flight hall being designed by UC Davis will be a 70-by-40-foot barn with rollup doors where the birds can fly and maneuver. Tiny, reflective sticker dots will be placed on their feathers and wings. More than 40 high-resolution motion-capture cameras will be installed that use infrared light to pick up points of the highly reflective stickers on the birds. Eight high-speed cameras will also be placed in the hall. All these cameras will be able to capture the birds’ motion from all different angles, like cameras at an NFL game showing a replay.

“The work that we’re doing is really looking at trying to bridge between small UAS, which are things like quadcopters that can perform really cool maneuvers and move things fast. And you have these large UAVs that have these fixed-wing configurations, and they can fly for a really long period of time. And birds fit this perfectly — they do both these awesome maneuvers and fly for long periods of time. And so that’s something that DOD is really interested in, this idea of being able to maneuver better and adapt better to variable environments, and animals are just so great at that,” says Harvey, who is using her Ph.D. students to help study the birds’ flight paths. “You see them do these cool trajectories. What are they doing to make it happen? What do we need to build into an aircraft to do that?”

The UC Davis researchers will not be designing the unmanned military aircraft they’re helping to create. But they are excited by a side benefit of their research — learning how to better rehab the injured birds at the raptor center. Cotton says right now they have these birds “whose current job is to just sit on a glove and look pretty.” But the testing they will be involved in will hopefully let their handlers know how to better build up their strength and the best time to release them back into the wild. They will also learn how the injured birds they’re using compare to the healthy ones. They’re hoping the research will lead to funding for staff and a new building as well.

Cotton, who helps run the California Raptor Center, gives all the credit to the birds for this project. “I think raptors capture our imagination,” she says. “They’re big. They’re very visible. They soar, they fly in such, really to us, majestic ways.”

Hawkins stresses their research is not just about imitating the flight of a raptor.

“What I hope to provide to the engineering community is an understanding that it is not desirable to just copy birds or copy animals, like biomimicry is not the end target,” she says. “The end target should be to understand the constraints and the objectives on these animals and their environments. And you use that information not only to better understand them, but to protect them.”

Get all the stories in our annual salute to women in leadership delivered to your inbox: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Saving Our Wildlife

When raging wildfires engulf our forests, what happens to the animals?

Capital Region researchers, veterinarians and advocates are

finding innovative ways to rehabilitate wildlife burned by

California’s raging wildfires.

Lake Tahoe Is Enjoying Its Best Clarity in 40 Years

While the leaders of the Lake Tahoe region deal with the impact of millions of visitors each year and the trash they leave behind, the lake itself is currently the clearest it has been since the 1980s.

The Delta in Decline

Wildlife and businesses in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta are suffering from lack of fresh water

The life cycle of a salmon, so the story goes, is a heroic journey. The fish emerge from fertilized eggs in a river bed, swim to the ocean where they spend most of their lives and return to give birth in the exact place where they were born.