The year was 1943, the world was at war and Dick Bertolucci cruised the streets of Sacramento in his first car — a black ’33 Chevy Roadster. He was 13 and didn’t have a license.

It was a gift from his dad, who worked downtown at the Chevrolet dealership and did custom motor work at home after hours. Back then, Bertolucci helped out by cleaning car parts in their garage. He told his father he wanted to build motors, but he said no and told him to repair a dent on the fender of his Roadster instead.

“I said, ‘Show me how,’” Bertolucci says. “So he did. And I went around clearing up all the little dents. That’s how I got into custom body work.”

Little dents grew into big jobs, and Bertolucci has been on the frontlines of the Sacramento custom car business ever since. He fixed up cars for World War II soldiers, customizing Model A and ’32 Fords. He was there to watch them race these hopped-up hot rods at the old dirt track called the Lazy J Speedway. He was there when they formed the Capitol Auto Club and came up with the idea to showcase their custom cars in what would become the first Sacramento Autorama in 1950.

“I had several cars that I built in the first Autorama,” says Bertolucci, whose wife, Beverly, remembers selling tickets for less than a dollar. “At least three of the cars that I worked on won awards.”

Over the years, the Autorama has relocated throughout the city as the number of entries and visitors exploded. In its first year, the show attracted a few hundred spectators. Last year, 43,000 visitors came to see the radical custom and exotic cars.

Now in its 60th year, the Sacramento Autorama is one of the longest running indoor car shows in the world. At the Cal Expo Fairgrounds from Feb. 19 to 21, more than 500 of the country’s finest custom cars, hot rods, classics, motorcycles and specialty vehicles will compete for cash and prizes. An additional 1,000 cars will be on display in a designated parking area.

The show gives more than 400 awards away for entries in the hot rod, street machine, restored, custom, motorcycle, suede and truck categories. Judges assess the lines, look and feel of the cars. One of those judges will be Bertolucci, a man so respected in the field that one of the trophies is named after him: “The Dick Bertolucci Award for Automotive Excellence” goes to a 1972 or older hot rod or custom car that Bertolucci decides has the best “assembly, fit, finish and detail.”

“Everything’s got to be just right,” he says. “I try to pick a car that’s as perfect as possible.”

That same obsession with custom perfection fueled the decades he spent running his company, Bertolucci’s Body and Fender Shop. Throughout the ’50s and ’60s, as he moved into bigger garages and hired staff, he built a reputation for doing quality custom work — especially when Corvettes surfaced in 1953.

“No one knew how to work with fiberglass,” Bertolucci says. “I had a monopoly on Corvettes for a few years.”

By 1974, he had 25 people working for him and had taken over a 25,000-square-foot building on 33rd Street and Stockton Boulevard. When custom work wasn’t covering the bills, Bertolucci turned to standard car repairs.

In recent years, custom car shop owners have had to modify their business hours and staff to stay afloat. Body shops nationwide saw increased competition in 2008 and 2009 as consumers saw body work as a nonessential service, according to a report by IBISWorld Inc., a Santa Monica-based researcher. Wages make up 35 percent of expenses in body shops, according to the report, with profit at less than 5 percent.

Bertolucci retired in 1975, but after hitting its peak in 2005, his business — now run by his five daughters and his son — began to stall. The past four years, he says, the company has laid off 20 of its 50 employees.

“You have a different consumer now,” says Terri Parra, Bertolucci’s daughter. “Because times are tough, a lot of people are not getting their cars fixed. They’re just keeping the money.”

To stay on track, they opened the shop for half days on Saturdays and started running radio spots and magazine ads. It started off slow, Parra says, but business is picking back up.

Across the city, the recession choked the custom car building community, in which, for many, money is merely a means to an end. The real value for those who restore or modernize classic cars comes from the work.

Take Ed Umland, who quit his job as a division manager for a precast manufacturing company three years ago to pursue his passion for building cars. Last year, he opened Eddie’s Chop Shop in Orangevale. He realizes he started his business at the worst possible time, and that the job transition chopped his income.

He doesn’t care. Working with his hands and meeting people who share his love for hot rods makes it all worth it.

“It’s not like a real job,” Umland says. “Cars are their passion. That’s the fun part of their day. They’ll skip a meal before they skip getting work done on their cars. I have no regrets.”

For Bertolucci, life is all about making something old new again, customizing vintage cars to keep up with the times, but never forgetting from when they came. “That’s why I got these old cars,” he says. “I remember them. I grew up with them.”

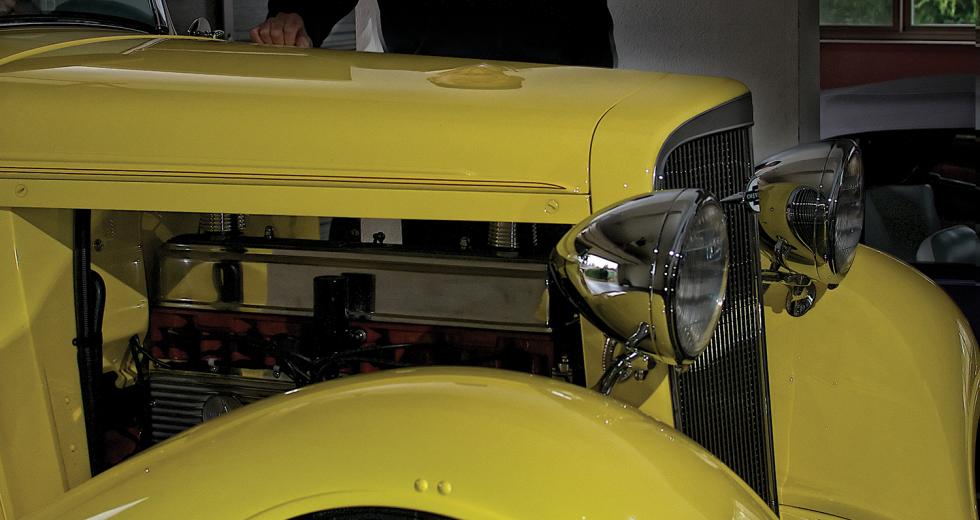

It’s 2010, U.S. troops are fighting a different war and Dick Bertolucci, age 81, cruises through his golden years. Down in his garage, he keeps another ’33 Chevy Roadster, this one yellow with blood-red interior and completely dent-free.

Recommended For You

Classics Gone Green

A new take on an old favorite

Gary Morton has a dream and a car. If his dream comes true, like those of Henry Ford and Karl Benz before him, Morton will turn his prototype into a car company.

But Morton is not looking to build a big assembly plant or an extensive dealer network. His production will be limited to just one model that will offer baby boomers the nostalgia of the muscle cars they drove in their youth alongside their modern commitment to a pollution-free environment.

Need for Speed

A peek at Bill McAnally's NASCAR

Bill McAnally owns 70,000 square feet of shop space – split between his race shop and automotive care business – and 31 race cars built on site at Bill McAnally Racing NAPA AutoCare Center in Roseville.