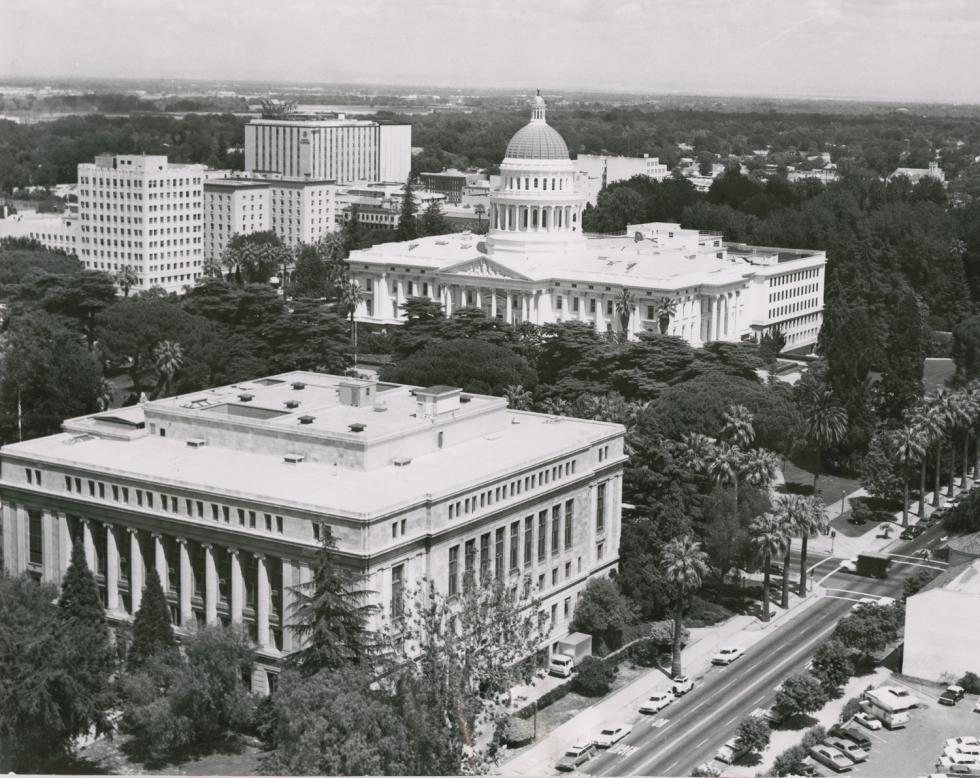

The Stanley Mosk Library and Courts building in downtown Sacramento was in dire need of a rehabilitative makeover to bring back its historic beauty.

Built in 1928, much of the building’s infrastructure and some of its architectural features had deteriorated and required repair. The five-story structure, designed by Weeks & Day, had outdated systems and failed to meet accessibility and sustainability standards, and over time, had undergone a number of modifications that were less than sympathetic to the building.

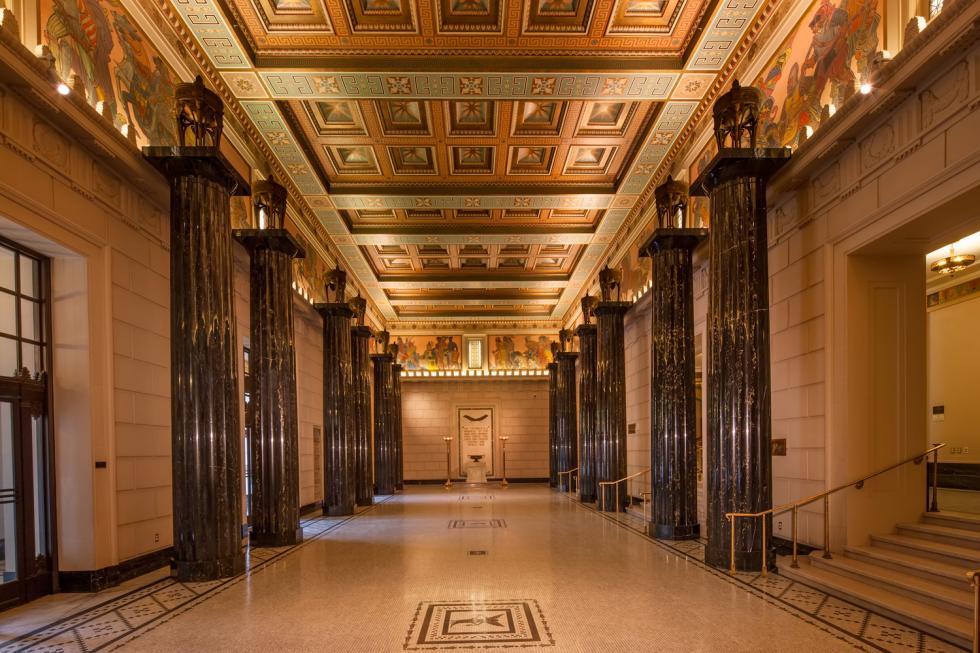

The interior of the Stanley Mosk Library and Courts

building.Photo courtesy Ed Asmus Photography

The building houses the State of California’s historic and literary collections, library services, the California Supreme Court Chambers and offices, the Third District Court of Appeal and for six days a year, the California Supreme Court.

In 2005, the State issued a public request for qualifications for the rehabilitation project. San Francisco-based preservation architects, Carey & Co. (which recently became part of TreanorHL), ultimately won the job. The architects — who specialize in historic buildings — had a tall order to bring the Library and Courts building into the modern era, while preserving its historic roots. When working with historic buildings, architects must adhere to specific national standards. For this particular building, the architects followed the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties, which promotes historic preservation best practices that help protect the nation’s cultural resources.

To start, the firm systematically evaluated the building for its character-defining features, including those they wanted to preserve and reuse in the finished project.

“In historic buildings like Library and Courts, there is usually a hierarchy of spaces,” says Nancy Goldenberg, Carey & Co.’s principal architect and architectural historian. “There are spaces that are very elaborate and we try to touch them as little as possible, and then there are more utilitarian spaces that are a little more flexible for alterations.”

The Stanley Mosk Library and Courts building shown here during

its construction in the late 1920s. Photo courtesy California

State Library

Goldenberg consulted with Tim Brandt, senior restoration architect for the California Office of Historic Preservation, which reviews all work done on historic buildings. According to Brandt, the challenges were fairly minor, a fact he attributes to working with experienced preservation architects, and occupants invested in the process.

In the mid-1900s, two light wells that brought daylight into the interior of the Library and Courts building were covered to install a new air conditioning system. Carey & Co. reopened both light wells, allowing more natural light to flood the interior corridors, rooms and main staircase. On the third floor, the architects uncovered the original terrazzo floor by removing a catalog room counter that had been added in the 1960s. Two historic elevators were restored and lifts to access the entry were added.

The firm also needed to update the mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems, and add fire sprinklers, which proved challenging. Installing the sprinklers would require cutting into the elaborate ceilings, so the architects sought an alternative. They found a state-of-the-art European mist system that uses less water, extinguishes fires faster and significantly reduces the water damage. This was the first time the system had been used in California, so extra fire alarms and detection devices were required by the fire marshal.

The project had to meet LEED Silver certification requirements. To do this, the architects installed more efficient mechanical and electrical systems and irrigation, and replaced the bathroom toilets and faucets with low-flow fixtures. The original sinks, and oak and marble stall doors were preserved. They also gained LEED points for the building’s proximity to public transportation and completing the hazardous materials abatement.

Historic images of the Stanley Mosk Library and Courts building

in Sacramento.Photo courtesy California State Library

The building’s exterior also got a facelift. Repairs were made to the original granite and terra cotta façade, and the whole structure was cleaned. A new roof was installed, and a mechanical penthouse was designed to house and hide some of the systems equipment.

All of the work was completed with little impact to the historically-significant architecture and art, including works by sculptor Edward Field Sanford Jr., and muralists Maynard Dixon and Frank Van Sloun. Inside, artwork includes plaster ceilings with facial busts accompanied by carved inscriptions of prominent authors, such as Bunyan, Dickens, Browning, Hugo and Tolstoy.

In all, the $37 million project took nearly a decade to complete from the initial request in 2005 to the grand opening in 2014. The project was temporarily put on hold during the Great Recession while the State reevaluated its obligations. The work was allowed to move forward because the project was so far along. During this time, contractors were hungry for work and extremely competitive with pricing, which helped save the State about 30 percent from the estimated cost. In 2016, the building was certified LEED Silver.

“We did a little bit of everything on this project,” Goldenberg says. “The building looked really fresh and clean when we were done and was restored to its original, historic beauty with some efficient, modern upgrades.”