In 1991, Gregory Perkins was a Sacramento corrections officer struck by a calling to make a difference. He realized that most greeting cards lacked representation of the African American community. Perkins worked with his cousin, an artist, to develop three Afrocentric greeting card designs in an effort to create what he calls an “uplifting product that African Americans can take pride in.”

Initially, Perkins worked out of his garage in south Sacramento but was blown away by the demand for his small line of products while attending a greeting card trade show in 1992, where he landed a major account with 500 stores (he says the chain has since closed). “That was major for us, especially as a small company,” he says. “Because it’s all about survival the first few years, right? You’ve got to survive before you thrive.”

African American Expressions started with just three greeting

card designs and now has a line of nearly 850 items, including

figurines and calendars.

Today, Perkins operates his company, African American Expressions, out of a 42,000-square-foot warehouse in Sacramento, and sells around 2.5 million cards annually, with over 500 original designs. The holiday season is unsurprisingly the company’s busiest, and between September and December Perkins says it averages 400 orders a day. Some of these come from large accounts such as Walmart, though his core clients are mom-and-pop shops across the nation, including Underground Books in Oak Park, and catalog sales from direct sellers. “I never thought it would be as big as it is,” Perkins says.

African American Expressions warehouse employees prepare

shipments. CEO Greg Perkins says the company averages 400 orders

a day during peak season.

Americans purchase about 6.5 billion greeting cards each year; with annual retail sales of greeting cards estimated between $7 billion to $8 billion, according to a 2012 report (the most recent available) from the Washington, D.C.-based Greeting Card Association, which was established in 1941. The GCA’s first comprehensive benchmarking survey of the industry, released earlier this year, found that more than half of card makers, designers and publishers said the industry has either greatly improved, improved or remained the same. Other reports show that despite this positivity, industry revenue has been shrinking as customers shift to digital alternatives.

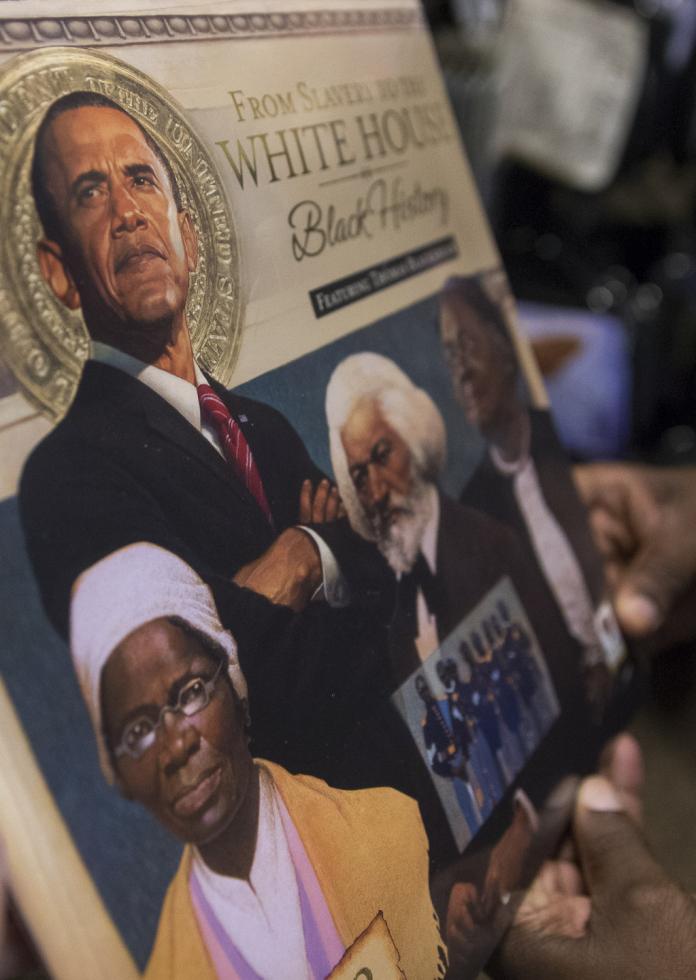

One of African American Expressions all-time most popular

products is the “From Slavery to the White House” calendar line,

which boomed after Barack Obama won the 2008 presidential

election.

Perkins credits his success, in part, to filling a demand for black representation that isn’t being met elsewhere. “We serve a need that wasn’t being served,” he says. “We get that everywhere we go.” The company is big enough to have earned a nickname as the “Black Hallmark of America,” which Perkins says is because his is the largest black-owned greeting card company in the U.S., with just two competitors both in the Los Angeles area.

Over the years, African American Expressions’ inventory has expanded to include not just greeting cards, but ornaments, calendars, figurines, stationery, bags and more — the company now has a line of about 850 items total. One of the company’s most successful products was a “From Slavery to the White House” 2008 calendar, featuring inspirational images of black leaders. It was so popular, in fact, that Perkins has released updated versions each year since. Earlier this year, the company announced the launch of a new Maya Angelou themed collection of stationery and gifts.

Allen Scott is the warehouse lead who says he went from “homeless

to homeowner” after starting work with African American

Expressions nearly five years ago.

Perkins is largely motivated by his Christian faith, which has compelled him to hire people he knows are experiencing homelessness.

Allen Scott, the African American Expressions warehouse lead, is one of those hires. Scott was part of a group of eight hires that Perkins became acquainted with through a local church. Since Scott started in the warehouse nearly five years ago, he says he has gone from “homeless to homeowner,” purchasing a home for himself and his family in Antelope nearly two years ago. Today, Scott oversees the orders, trains new workers, and manages shipments and receiving, among other responsibilities

Perkins has been uplifted by the impact of his company on the customers he serves. He says he was even solicited for an autograph at a trade show, by a woman who told him that the commission she earned from selling his products helped her feed her family for years. “You never know what you’re doing out there until you hear the community’s response,” he says.