Jeff Musser was an artistic child who went on to graduate from the Art Institute of Chicago in 2000 with his bachelor’s degree in graphic design. He then spent two years at an ad agency in Chicago managing creative for McDonald’s Happy Meals. Despite a respectable salary, Musser was anything but happy.

“I hated it,” he says. Musser would come home from the job creatively zapped, and have nothing left to give his personal artistic pursuits. Thankfully, he says, he was laid off. He moved back home to Sacramento and patched together odd jobs that kept his creativity intact.

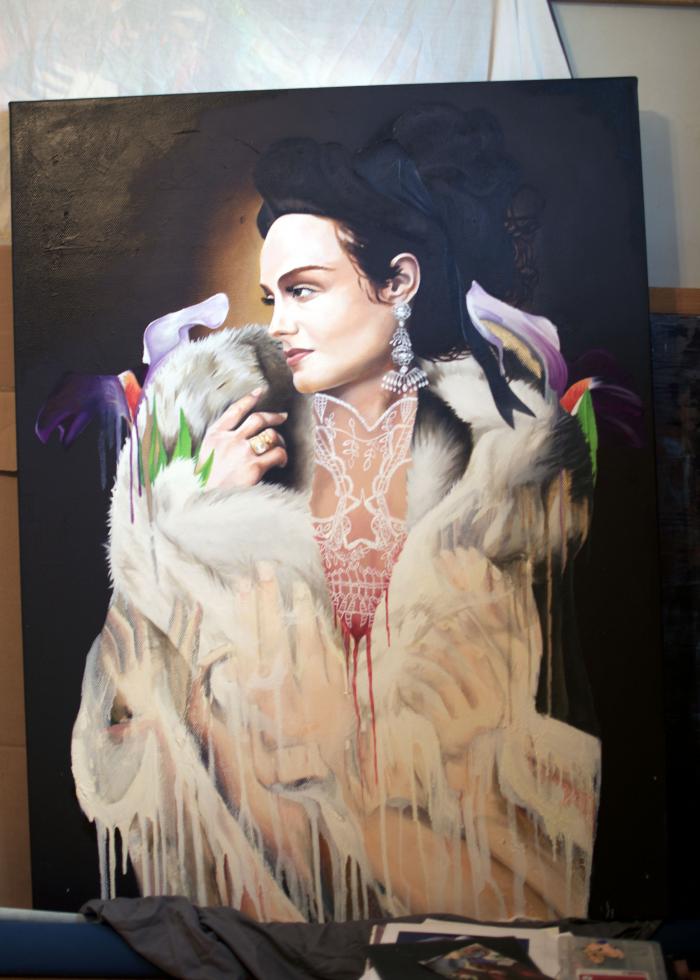

Musser incorporates collage and abstract stylings into his

classic European master realism paintings (Photo: Eva Roethler)

In 2013, Musser felt too comfortable with his routine and moved to China. “The first six months I was there I went back and forth between thinking, ‘This is the smartest thing I’ve ever done’ or ‘It’s the dumbest.’ I didn’t know,” he says.

The move ended up triggering a creative evolution, as he began to incorporate collage and abstract stylings into his classic European master realism paintings. But Musser returned to Sacramento again three years ago to be closer to his family while his father dealt with some health problems. He has since become actively engaged in the local creative community, acting as a past juror for KVIE’s annual art auction and a muralist for Wide Open Walls in 2017.

Musser, who says he now spends 60 percent of his time actually creating art and the other 40 percent writing proposals, focuses on work that is rich with symbolism — even down to the materials he uses. A recent piece inspired by the systemic racism Musser sees in the world used non-archival cardboard which will eventually disintegrate, in part to convey lost hope. Pieces from this cardboard series will be part of a group show, “Concrete And Adrift: On The Poverty Line” at the Alexandria Museum Of Art this spring in Alexandria, Louisiana. “I don’t want the work to be in your face and easy,” he says. “I want you to look at it and it reveals itself in layers, like any good story, it takes a while to be absorbed.”

Comstock’s caught up with Musser to talk about his creative work and being part of the local arts community.

Tell me about your creative background.

The theory, once I graduated [from the Art Institute of Chicago], was that I could put painting to the side because those student loans are not going away and I needed to pay them off. So it was supposed to be graphic design during the day, then come home and paint at night. I quickly learned that when I gave all of myself creatively to ‘the man’ during the day in the office, I had nothing left when I came home. I could only paint on the weekends. That was not sustainable. [Then I got laid off.] There was a nice euphoria for about a month, I got a decent severance, and I didn’t have much debt at the time. But then there was the reality of, OK, if I’m going to pursue painting full-time, there are realities of that: How am I going to pay rent? Buy food? It’s been a very tough road. I’ve had all sorts of weird jobs. But I learned that if I was to get a job during the day that would pay the bills it could in no way be creative for someone else.

What kind of jobs work for you?

I found that when I was in China, for the first year and a half and I was teaching, it was fun. It took physical energy because I was dealing with children, and oftentimes I’d have classrooms of 40 or close to 50 kids. So physically, I would be exhausted on some days, but I could still go back to my apartment and I could paint and it was fine. As long as I don’t give the creativity to someone else, where I have no say, it was fine. Teaching was OK. I worked for HealthNet for six months 10 or so years ago, in customer service. I worked for a medical supply delivery company, which was pretty easy.

You got into painting when you were in college. What prompted you to start incorporating other mediums?

“Dawn Of The Dying Day” Oil on canvas. 48″ x 60″. 2014. After

living in China, Musser says his work evolved to include more

abstract stylings and collage, as seen in this painting. (Photo

courtesy Jeff Musser)

The main reason why I went to China was to break out of my routines and try something new. When I first arrived, I lived in a relatively small city — in terms of China’s scale — but it was still six or seven times bigger than Sacramento. There’s so much stimulus coming at you. There’s sights, sounds and smells — it was an assault of the senses. My mode of working back in the states would not have suited me there. So I had these things coming at me and I had to find a way to piece them all together in a puzzle that reflected my time and my experience of not being able to get my footing when I first arrived. Once I found collage, it was like OK, I enjoy this. It’s different. It’s new. I don’t quite know what I’m doing, then it gradually moved toward: Now that I know I can do this with collage and painting, how do I take my old work and the knowledge of painting in a photorealistic way — the old master technique of glazing and dramatic lighting — how do I marry and merge those two and have it mean something?

What is the bread and butter that has supported your creative work?

Commissioned portraits. Collaborating with other artists on their projects. I help a couple of my friends down in L.A., doing work for movie sets or TV shows, painting backdrops, that kind of stuff. And murals.

Tell me about how you engage with the local creative community.

I did a mural for Wide Open Walls in 2017 and I was a journeyman painter for the Wide Open Walls festival this past year, so I worked on several murals during the course of the festival. That was all out of my love for the project and wanting to work with artists that I’ve always wanted to work with like Herakut, Mateus Bailon and Camille Rose Garcia.

Related: Art Exposed: Sarah Golden

Related: Art Exposed: Alejandra Calderon

Lately, I’ve been here [in my studio] working, but I make an effort to go out and see what other people are doing. I’ll call people and say, ‘You want to get a beer?’ If I know people are out and about working on a mural, I’ll ride my bike over and say what’s up. You have to get engaged, and you have to want to do it. I mean, I understand being self-absorbed and focused — but you have to remember that you are part of a community. You have to contribute because it’s not all about you all the time.

How do you engage in marketing or branding to raise awareness for what you’re doing?

Lately, for the past few years, it’s been me seeking out opportunities or taking advantage of things that come my way that I think will be useful. But I know, now, that I will have to collaborate with someone else whose job is solely that. This takes up a tremendous amount of time, with the proposals and fellowships there have been points where I’m either too busy to devote a lot of time to it, or there’s only so far I can take my own writing. So I find people I know are grant writers or have experience, and ask how much it would cost to spend two or three hours on it and then say, ‘Here’s the outline, turn my ramblings into a gold nugget and I’ll pay you handsomely for it.’ I’m getting to the point where I can’t handle it all on my own.

Tell me about a piece of work you are the most proud to have created.

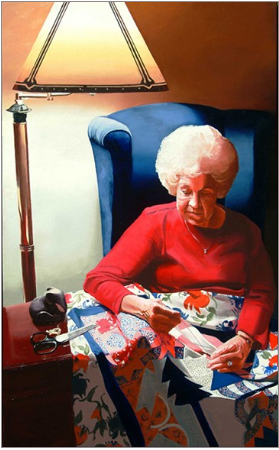

“Portrait Of My Grandmother’’ Oil on canvas. 36″ x 48″. 2005.

Before living in China, Musser says his style leaned toward

European master realism, as seen in this painting of his

grandmother. (Photo courtesy Jeff Musser)

About 10 years ago I painted a portrait of my grandmother. … It was one of the best paintings I’ve ever done. Someone else saw it, and it reminded them of their own mother and the person who saw the painting said, ‘I just started crying because I loved her so much, and she looks so much like my own mother. You’ve captured the spirit of a generation, and I love it.’ So not only did I make someone cry without really setting out to, they also bought it. It shouldn’t be a deciding factor, but when someone makes a connection with your work at that level, where they’re willing to exchange money for it. It’s different than just doing commission work, or something you know will sell.

What makes it different?

When I do commission work, I know I’m doing it for a certain amount of money. Or if I’m doing something for a commercial, I know they’re using it to sell a product, or using it as a cool backdrop for a particular scene. So in a sense, that’s just like me going to an office job — that’s work. Any artist, or person, that says, ‘You find something you love and you’ll never work again in your life.’ Well that’s complete [expletive]. There are some days where I would love to just sit and binge on the new season of House of Cards, which I know I’m going to do in the near future — but I have to remember my self-imposed deadlines — that is just something that has to be done before I can sit down and see how House of Cards ends.

But when you go into your studio and create something that didn’t exist before and you love it and are proud of what you made and you show it out in the world, how it’s interpreted is not up to you. The work now has to take a journey that is it’s own. So if you can make someone cry, or push them to extreme anger, then you’ve done a good job. … That’s what it’s all about. Indifference, or no feeling at all, that’s the kiss of death because you’ve put all of this energy and time and your work gets out into the world and people are like, ‘Oh. That’s cool.’ It’s just like, ‘What are you talking about?’ That’s the kiss of death! You want to invoke something.