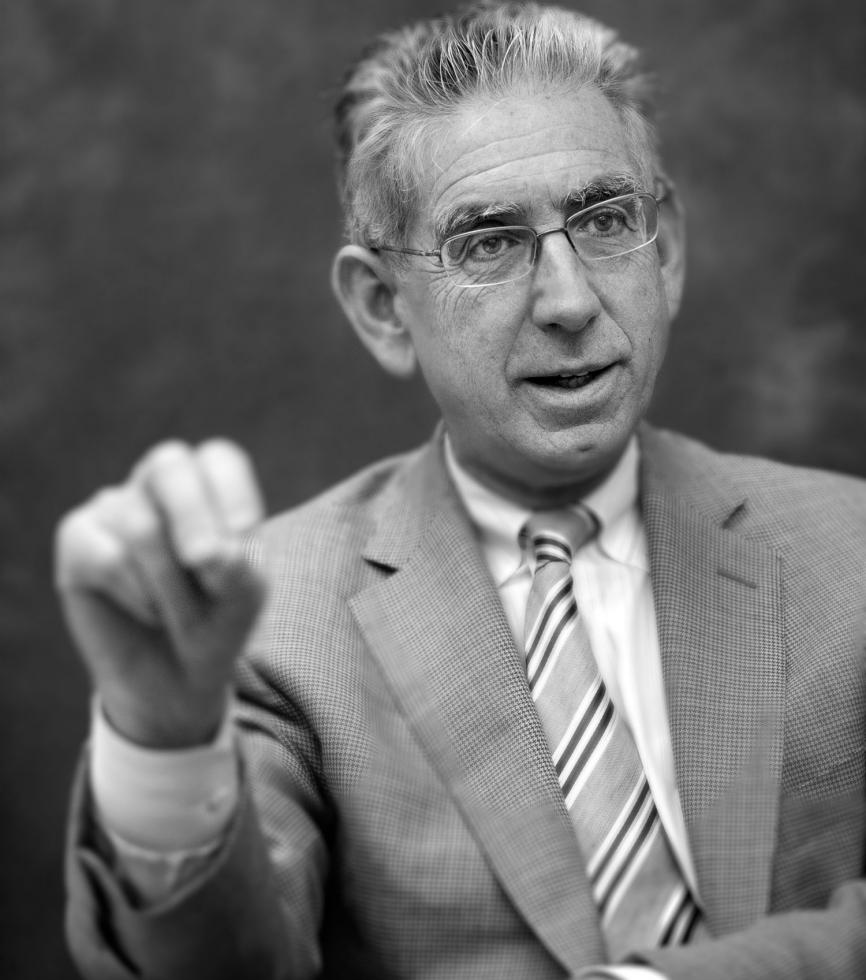

Former California State Treasurer Phil Angelides was tapped in 2009 to chair the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, a 10-member commission that Congress tasked with determining the causes of the Great Recession. After reviewing millions of pages of documents, interviewing more than 700 people and holding 19 days of hearings, the commission issued its findings in January. We sat down with Angelides in his Sacramento office recently to discuss those findings.

Comstock’s: The report details

shocking systemic failures in our financial system. Even so, your

findings were not unanimous. Why was that?

Angelides: Obviously we all came in with a certain level

of preconception, like most Americans. Everyone knew something

about this crisis. But it was very much a journey of revelations.

I came in thinking I had a pretty good grasp and knowledge of the

financial system. But as we got into our inquiry, we were

fascinated, surprised, shocked and appalled by what we saw and,

for me personally, just the sheer level of gambling that was

happening on Wall Street. I had, as I think many people do, this

notion that Wall Street was there to serve the real economy and

provide capital to grow businesses and jobs, and I found

something quite different. Although our report was not unanimous

— there were five Democrats and one Independent who signed onto

the report, with two separate dissents by the Republicans — I can

at least speak for the commission as a whole in that our

conclusions are based in facts.

Comstock’s: You’ve stated that

your job was not to be prosecutors, but to find out what was

going on and to present the evidence and facts the way you saw

them. Still, a lot of folks have questioned why we aren’t seeing

the people responsible for this in jail.

Angelides: This is the most frequently asked question I

get. While we were not set up as prosecutors, we did have a legal

obligation, given to us by Congress, that if we found potential

violations of law, we were to refer that information to the

attorney general of the U.S. and the appropriate state officials.

We fulfilled those responsibilities. Obviously we’re not at

liberty to talk about specific cases, but we did in fact forward

material to the appropriate law enforcement authorities.

Comstock’s: Do you anticipate

the Department of Justice prosecuting any of these cases?

Angelides: It’s my hope that our investigation is viewed

as a start, not an end, and the prosecutors follow up. I think

there are two critically important issues here. One is that

people need to know the justice system has only one set of rules,

not one set for people of enormous wealth and power and another

for everyone else. I think this notion of fairness is vitally

important. But I think deterrence is also important. I’ve looked

at a number of the civil settlements that have come out of this,

where defendants have made tens of millions, or even billions of

dollars, both individuals and firms. They settle for pennies on

the dollar and admit no wrongdoing. Heck, if a guy robbed a

7-Eleven, stole $500 and the next day could settle for $25 and no

admission of wrongdoing, he’ll be back doing it the next night.

So I do think deterrence is a serious matter. As for cases being

pursued, look at it this way. The full implosion of the crisis

came at the end of 2008. In 2009, the country is still shaking

and wobbling, and the real question is, “Are we going to plunge

into a Great Depression?” It’s not until 2010 that the real

investigations began. We’re still just learning each and every

day about what happened here. So my hope is the investigation

continues and cases are pursued.

Comstock’s: We saw a fairly

strong resistance from some members of Congress against greater

regulation of our financial system. In that regard, was Congress

trying to kill the reforms that folks like you say are so

desperately needed?

Angelides: The House of Representatives sure tried. They

and their political allies on Wall Street made a very deliberate

effort to do it; there’s no question about it. In fact, very

little has changed since our financial world came apart in 2008.

Wall Street firms are still making an enormous amount of money

through risky trading activities. There’s a greater concentration

in power and assets in fewer banks than ever before. I mean, if

“too big to fail” was a problem before, it’s an even bigger

problem now. Bloomberg recently came out with some new numbers

that showed that the biggest 10 banks control 77 percent of the

banking assets in this country now. So if one of them gets in

trouble, it’s hard to imagine the U.S. government won’t rescue

them.

Comstock’s: You mentioned “too

big to fail,” which we all heard as a rationale for the Troubled

Asset Relief Program, the taxpayer dollars Washington used to

prop up the financial system. A lot of people think TARP was just

a bill of goods. Bottom line: Was the federal bailout

necessary?

Angelides: We tried to focus on a different question:

How in the heck did it come to be that in fall of 2008 the only

two choices this country appeared to have was either to allow the

financial system to collapse or to inject it with trillions of

dollars? I think that’s the question that’s central to this

country. Based on every document I read, the witnesses I heard,

the data I looked at, it’s pretty clear that when we got to

September of 2008, the financial system was in free fall, and we

had no alternative but to wade in and support the system. Now, it

could have been done in different ways. It could have been done

where we got much more in the way of change in behavior from

these financial institutions for the price of assistance. I’ll

give you one example: When the government came in and rescued

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, they imposed a condition that they

could no longer lobby Congress, given that they were now

essentially a taxpayer-supported institution. But almost no

constraints were put on the big banks. They got the cheap money

with almost no strings attached. I think that was problematic.

Comstock’s: Could this happen

again?

Angelides: Yes. In the wake of Great Depression, we

adopted reforms that did pretty well for us for several decades.

But they came out of a period of great pain, and they also came

out of a period where Wall Street itself was brought low. In this

instance, because of the enormous support from the American

taxpayer, Wall Street may have skipped a few beats for a few

months but pretty soon they were back at it. Profits by 2009 were

triple what they were in 2006, the year before the meltdown

began, and compensation at big publicly traded firms hit a record

high in 2010 of $135 billion. We’ve also seen the House try to

cut funding to the Securities and Exchange Commission and the

Commodity Futures Trading Commission. The SEC’s budget is $1.2

billion, but the House GOP leadership tried to cut it to $1

billion. The SEC this year will bring in about $1.8 million in

fines and fees, so it’s not about the budget. It was about

constraining the ability of regulators, who are already

outmatched by Wall Street, from doing their jobs. It’s the same

with the CFTC, which is charged with the herculean task of

regulating the over-the-counter derivatives market, which at one

point was about $600 trillion in size and was without any

regulation or transparency. The Dodd-Frank reform bill takes this

dark market and brings it on the public exchanges. It’s going to

be a very big task, but the House Republicans tried to cut their

budget by a third, which would have made it impossible for them

to do their work. So I definitely think the risk is there. In

some respects the economy is so slow right now. It’s like a boat

that’s not seaworthy. I’m afraid when this thing starts sailing

again that we’ll be very prone to the same risks we saw in the

run-up to the crisis. [Note: The SEC and CFTC have since received

slight increases in their 2011 operating budgets.]

Comstock’s: What does this

administration need to do to help prevent that from

happening?

Angelides: What the president needs to do is to more

forcefully advocate the case for reform. He needs to lay out for

the American people the risks that are still there and to really

show the American people his commitment to making fundamental

changes in the financial system. The opponents of reform have

done an extraordinary job of confusing people about the facts.

There is no question that by the time President Obama took office

in 2008, the damage had been done and the economy was in free

fall. But it does fall on him to make the case for reform, and I

am hoping he does that in the next two years.

Comstock’s: You’ve mentioned

that so many of the worst offenders have dodged their culpability

in this situation. Did anyone step forward to be accountable?

Angelides: Yes, Ben Bernanke. Most of the people we

interviewed would not accept any correlation between the risks

they took, the recklessness they engaged in and what happened to

our economy. But I found Bernanke was one of the few people

willing to be introspective and reflective. For example, he

agreed with our assessment that the Federal Reserve’s

unwillingness to control out-of-control mortgage lending was a

total failure. But he also pointed out to us that the damage was

so severe that by September of 2008, we were probably within a

week or two of 12 of the 13 major financial institutions

collapsing. So no one should ever forget how the system had come

completely apart, and how the recklessness of Wall Street got us

there. I hope those lessons are never forgotten.

Recommended For You

Where Is Phil Angelides Now?

It's been an eventful 25 years for this developer

Then:

The year was 1989. Comstock’s was in its infancy. Hometown boy Phil Angelides was featured in November, standing in the center of the historic Southern Pacific railroad station.

Love Thy Neighbor

Sacramentans love infill development – until it actually happens

Infill development is promoted as an antidote to suburban sprawl and environmental degradation and is championed by city planners, environmentalists and policy makers of all persuasions. But as local developers Paul Petrovich and Phil Angelides have long known, infill leads to fights over allegations of increased traffic or environmental hazards.