In 2013, a 10-year-old collie named Hoshi was diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma and needed to have her entire front jawbone removed. Using a 3-D-printed skull, UC Davis surgeons were able to shape and fit a titanium plate to form a new jawbone prior to the surgery. This reduced the surgery time, says Dr. Boaz Arzi, an oral surgeon at the school’s Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital.

“The anatomy in the skull is very complex, so it gives us an edge when we already have the plate bent before I go to the [operating room],’’ he says. To date, he says he’s used 3-D printing in about 10 surgeries over the course of three years.

Old School, New World

Three-dimensional printing is not new; Chuck Hull built the first 3-D printer in 1983, but it has only gone mainstream in the past few years. The technology is “an additive process that takes material from a storage space and deposits it in very small layers until it is fully built up into a three-dimensional object,’’ explains Steven Lucero, a mechanical engineer at the BME Fabrication Laboratory and a laboratory manager in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at UC Davis.

Users are now creating everything from human organs and limbs to handguns and musical instruments. Sales of 3-D printers, including materials and associated services, reached $2.5 billion globally in 2013, according to Canalys, which projects the market will reach $3.8 billion in 2014 and as much as $16.2 billion by 2018.

Medical Implementation

At UC Davis, 3-D printing is being done on a routine basis for oncologic cases and maxillofacial disorders, Arzi says. Although the vets use computed tomography (a CT scan) to create 2-D images that allow them to “see” details inside 3-D objects without slicing, “sometimes we have problems understanding 3-dimensional objects,” he says.

Arzi completed his fellowship in biomedical engineering and felt 3-D printing would be useful in helping veterinarians improve their surgical planning “to make it more precise and to help the (pet) owner learn what’s about to happen and to help them make a more educated decision,” about reconstructive surgery for their pets.

For example, veterinarians perform ankylosis surgery through bone fusion to fix stiff or immobile joints, he says. “In situations like this, when [the bones are] in a dangerous position, we can print the skull and do surgery on the 3-D-printed skull and see if our approach will be successful.

Not Impossible Labs in Venice, Calif., uses crowdsourcing to solve health care problems and has used 3-D printing on a number of projects. One of them is Project Daniel, named for a now-16-year-old Sudanese boy who lost his arms in a bomb explosion. With help from 3-D-printing company Printrbot plus engineers, neuroscientists and the inventor of a robotic hand, Project Daniel was started to build a prosthetics lab in Sudan’s Nuba Mountains. In November 2013, Daniel received a 3-D-printed prosthetic left arm.

Accessible Options

But the reach of 3-D printing goes beyond surgeons and scientists, as the machines have become increasingly accessible to everyone from hobbyists to aspiring inventors. The Brooklyn-based MakerBot is largely credited for bringing the devices to the masses, its printers allegedly as easy to assemble as IKEA furniture. In July, MakerBot’s Replicator printers were rolled out with demonstrations at a dozen Home Depot stores nationwide.

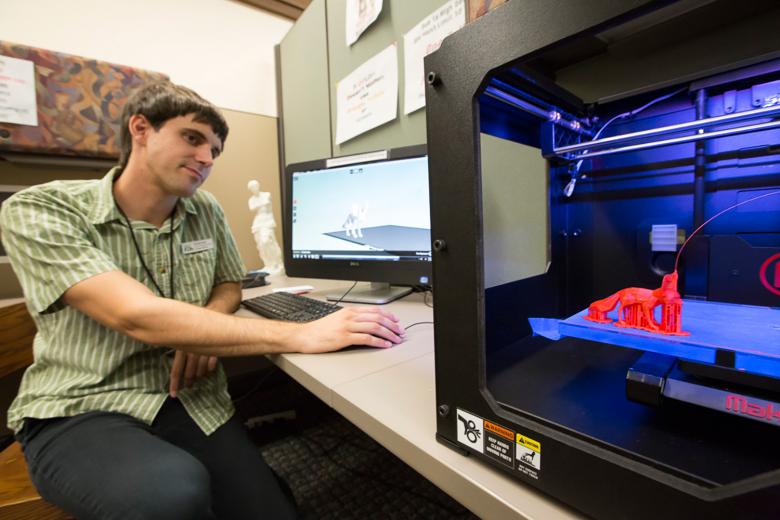

“MakerBot brought [the technology] to the mainstream because they make really affordable printers,’’ says Lori Easterwood, programming and partnerships coordinator for the Sacramento Public Library. The library has three MakerBot Replicator 2s and a Mojo 3-D printer in the Arcade branch.

The printers, which can be used at no cost, are in constant use and maintain a waiting list, Easterwood says. Some people come in to see what a 3-D printer looks like. Others have taught themselves how to use one and want to create 3-D items, she says. “They’re coming in and printing their inventions or a thing they need for their toaster because the knob broke, or whatever,’’ she says.

Charles Dale is the library technology assistant at the Design Spot, the Arcade branch’s 3-D lab and maker space. He says that because of the branch’s proximity to Sacramento State, a lot of the projects have been educational. “They have a mechanical engineering program that requires students to develop robots that perform certain tasks. [Students will] print the chassis for the robot,” he says. A group of high school robotics students also came in to print parts for underwater exploratory robots.

Prototyping Made Easy (and Affordable)

Nathan Zavaleta heard about Sacramento Library’s 3-D printer in 2013 while working at a helmet-making company. He and his boss became interested in working on some prototypes for a new product. They took the library’s introductory course on 3-D printing and watched a seminar on some of the programs the printers run on. That’s all it took to hook the 25-year-old Zavaleta.

“I had to go back and try it out for myself the next week,’’ he recalls. “My boss was just interested in some applications for the company. But I was very excited because the programs they were using were ones I was familiar with already from high school.”

An avid snowboarder, Zavaleta came up with an idea for a tool that would tighten up his bindings. He spent two to three hours a day printing prototypes on the 3-D printer, and six months later he had HexFlex — a multi-tool that boasts a whopping 15 tools. In October 2013, he launched a Kickstarter campaign with the goal of raising $10,000 to take HexFlex to market — and raised that amount in three days.

Zavaleta says there are “lots of multi-tools out there, but I think the design is what catches people’s eyes.” The tool, which is shaped like a snowflake, is now sold online through amazon.com and on the HexFlex website as well as through some local dealers. He says he’s hoping to have it in broader distribution before winter.

Zavaleta’s HexFlex tool is the library’s claim to fame, Easterwood says.

“The library’s helping (people) achieve their dreams or at least their ideas,’’ she says. “Sometimes it doesn’t work, but sometimes it does.”

Dale says the library does not allow anything dangerous to be printed, such as firearms. Users are required to sign a disclaimer in advance, and there is a 3-hour time limit, though the average wait time has been growing steadily. “More traffic makes it a scarcer resource for everyone,” he says. “That being said, the more activity the more likely the program will be successful and grow.”

The printers, along with Design Spot, were made possibe by state and federal grants. Design Spot opened last year with a couple of “makers in residence,” including Alan Ware, who manages the 3-D printer at Hacker Lab in Sacramento.

Hacker Lab in Sacramento is a combination hacker/maker space and business incubator that offers classes which introduce 3-D printing, covering both the mechanics of the device and design tools and processes. Ware has seen a lot of prototypes and school projects, as well as hobbyists creating things like do-it-yourself drones known as Quadcopters.

Room to Improve

Sales of consumer 3-D printer hardware and material are expected to exceed the $1 billion mark by 2018, compared to just over $75 million this year, according to Juniper Research. But even with such rapid growth predicted, there is still room for improvement in areas including speed, print quality and cost, observers say.

While 3-D printers have come a long way, they are still “not exactly out-of-the-box ready,” Easterwood says. “You have to spend a lot of time getting up to speed on the design process.”

Speed is also an issue. Ware says anything “worthwhile” will take at least 45 minutes, and an object the size of a teacup could take an hour or two to print.

“People are used to making things fast,” he says, “but it takes time to build things. Six hours may seem like a long time to build a part, but if you ordered it online it might take a week.” And he says that, over time, the process will only get faster.

In order for 3-D printing to successfully find a mainstream market among consumers, “it needs to widen the applications available that integrate consumer lifestyles and drive a number of applications beyond professional printing,” writes Juniper analyst Nitin Bhas in the report Consumer 3-D Printing & Scanning: Service Models, Devices & Opportunities 2014-2018.

Additionally, Bhas says that, similar to the mobile device ecosystem, content will be critical to the success of consumer 3-D printing. Content can be most easily provided through apps or online portals that enhance the functionality of the 3-D printer. Some of this is already being done. For example, 3-D printer company MakerBot, via its Thingiverse website, allows users to share digital designs primarily created using open source hardware. According to the site, more than 100,000 3-D models have been uploaded by the Thingiverse community.

“The technology needs to get a lot cheaper,’’ says UC Davis’ Lucero. “The printers are too expensive and too slow for them to be used in mainstream manufacturing. Those are the two biggest handicaps right now.” That said, if you’re making a one-off item or even up to 100 widgets, speed isn’t a big factor. It becomes more problematic when you need to manufacture thousands of units of something, Lucero notes. “That’s when you typically go with a more traditional manufacturing technique.”

Also, because 3-D printers come in so many shapes and sizes, at the lower end of spectrum, he says the machines that are the least expensive need to get much more accurate. “They’re limited in terms of what they can do based on their price point. Over time I think the lower-end machines will become capable of what the higher-end machines can do today and when that happens, more people will adopt them.”

Zavaleta, for one, already has. He now has a 3-D printer in his home and thinks its use will go further beyond the “wow factor” once there are more types of material available, like rubberized filament. “That would maybe open the door for other things,’’ he says.

Already the technology is proving its merits in the medical community. Arzi says he only has positive things to say about the technology. “It helps us advance our level of care. It helps us to do client education and also helps the teaching mission.”

Digital editor Allison Joy contributed to this story

Sick of missing out? Sign up for our weekly newsletter highlighting our most popular content. Or take it a step further and become a print subscriber — it’s both glossy and affordable!