Fifty years after the VIII Olympic Winter Games in 1960 brought the world to the slopes of Squaw Valley USA, and after years of toil and dashed hopes, a two-state effort aimed at bringing the games back to the Reno-Tahoe region in 2022 is gathering steam.

Past efforts have failed over anything from timing to geopolitics. This one — still low-key but expected to speed up over the next year — might go the distance.

The potential prize is enormous. The Olympics means billions of dollars spent; accelerated construction of roads, airports and transit; thousands of jobs and a spotlight on the region before a global audience. The tourism afterglow of the Games can last for years.

But getting there involves a massive planning effort, long-term work to build global awareness and plenty of fundraising, all without a wrong step in the minefields of public opinion, environmental concerns and Olympic site selection. Several sources interviewed for this story made a special point to stress that there could be no Olympic bid until a formal invitation was issued. Officials will choose the host of the 2022 Winter Games in 2015, so reviewing potential U.S. host cities is expected to start in 2012.

“There are no candidate cities yet. There are no bid cities yet,” says Jack Kelly, a Kentucky-based consultant who has been advising the Reno Tahoe Winter Games Coalition, the nonprofit formed in 2001 to pursue a return of the Games to the Tahoe region. But regions can start the groundwork officials will want to see when they begin to assess potential hosts.

With that in mind, coalition members attended the Winter Games in Vancouver this year, racking up contacts and face time. They’ve been in touch with Olympic athletes, past and present, who could be goodwill ambassadors and fundraisers. They’re working to form a nonprofit Lake Tahoe Regional Sports Commission, which would organize national and world-level competitions in California and Nevada, building a track record and raising the region’s profile.

With the heritage of the 1960 Games, “we’re already credible in the international community,” says Jon Killoran, chief executive of the coalition. “Now we need to be ready.”

The coalition has four broad strategies to get there, says

vice-chair Jim Hartley, a vice president with CH2M Hill in

Sacramento:

• Build up a funding base

• Build community and regional support from the Carson Valley to

the San Francisco Bay Area and possibly Las Vegas

• Build a brand rooted in the region’s Olympic history, and

• Bolster its ranks with more volunteers and backers.

“This is a year of change, and we’re right at the beginning of it,” Hartley says.

Says Kelly: “This is not a pipe dream. This is not science fiction. Other cities have been far less prepared than Reno/Tahoe is now.”

That included Squaw Valley itself, back in 1955 when the International Olympic Committee narrowly chose it as the site for the 1960 Games. Organizers scrambled to build hotels and restaurants, complete a passenger terminal at the Reno airport, and lay nearly 50 miles of four-lane highway as U.S. 40 near the ski area was replaced by the road now known as Interstate 80.

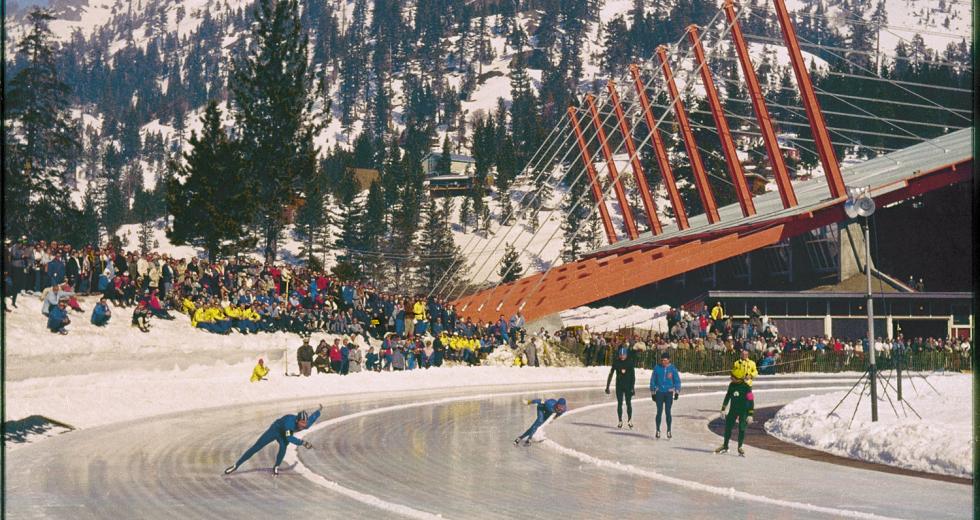

But Squaw Valley got its act together. The village hosted 665 athletes from 30 nations. There were some 250,000 ticketed spectators, according to David C. Antonucci’s “Snowball’s Chance: The Story of the 1960 Olympic Winter Games Squaw Valley & Lake Tahoe,” published last year.

Things have changed. At Squaw Valley in 1960, a snowy alpine meadow was firmed up with sawdust and used as a parking lot. At the Vancouver games in February, many spectators weren’t even allowed to use their cars; an event ticket was good for a transit ride to the venue.

The scale has changed, too. The Games in Vancouver featured 86 medal competitions and more than 2,600 registered athletes. In all, 1.6 million tickets were available.

And costs? The original cost projection for the 1960 Games was around $1 million, not counting highway construction. It eventually came in at around $13.5 million. That cost spike helped inspire a Colorado vote in 1972 that barred the use of tax dollars to hold the 1976 Winter Games in the Denver area, forcing the IOC to move the event to Innsbruck, Austria.

These days, an operating budget of $1.5 billion before capital improvements is considered typical, and the total price tag for the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi, Russia (including extensive capital projects) is estimated at more than $10 billion.

A Reno-Tahoe event likely would have a much lower price tag. Most of the estimated $1.5 billion operating budget would be covered by broadcast and licensing fees, sponsorships and ticket sales, backers say.

A 2003 survey of potential venues in the region that could serve the 2014 Games found that many ski resorts and other sites around the region were well suited to international sporting standards and Olympic crowds and rules. Some, the architect’s report found, could work with minor modifications or transportation improvements, others with waivers for the altitude or course layout. The region would need an Olympic-sized skating venue and a bobsled/luge track, the report noted.

But most modifications would be relatively inexpensive and new venues could be designed so that they remain useful long after the games end, Killoran says. “We don’t want any white elephants,” he says. “Does the region need a new long-track speed skating venue (in the long run)? No, but it needs a track and field center,” and a speed-skating track could be designed for easy conversion.

That’s an element potential Olympic hosts are stressing as the IOC scrutinizes not only the sporting and tourism aspects of the Games, but also their environmental and social effects.

For example, housing added for athletes and coaches could be converted after the games to ensure that affordable housing is available for workers in Tahoe and Truckee, says Ted Gaines, a California assemblyman and coalition board member. That could ultimately reduce traffic and pollution by cutting the need for workers to commute. “There’s great potential for infrastructure,” says Gaines, a Republican whose district includes Roseville. “We’ve talked about extending the Capital Corridor” commuter rail service, and a major event could accelerate other improvements, such as adding a second track to Union Pacific rail lines to allow more passenger trains.

Even the chance of an Olympiad can open the floodgates of government spending. Salt Lake City jumped from No. 23 on the Federal Aviation Administration list of capital priorities to No. 1 when it was awarded the 2002 Winter Games, Hartley says, and Utah’s capital and Park City are still reaping the benefits of spending on roads and light-rail. “Having the Olympics and having a certain deadline to meet accelerates the funding,” he says.

Coalition members stress that preparations aren’t all about more development. That’s a touchy subject in the Tahoe basin, where some say the 1960 Olympic spotlight hastened changes that have degraded the environment. Times, they say, have changed.

“These Olympics would be a little different,” says Nancy Cushing, the board chair at Squaw Valley Ski Corp. whose late husband, Alex, was a key player in bringing the 1960 Games to the region. “They’d be the greenest ever.”

Conservationists in the region have seen many development proposals dressed up in green, though. A position statement by the League to Save Lake Tahoe says the group wants to work collaboratively to examine the costs and benefits of an Olympics, but notes that government funding to restore and preserve Lake Tahoe might be diverted to highways and other projects related to the games, and that roads and development historically have degraded water quality.

“It surely is possible to take action to reverse the mistakes of the past, and those mistakes largely have to do with road building and other development,” says Rochelle Nason, executive director of the League. “The challenge would be dealing with one of the most sensitive and damaged watersheds in the United States.”

Backers of a Winter Games here talk about improving roads to cut runoff that pollutes Lake Tahoe, about water taxi service to reduce lakeside traffic, about fuel-cell powered vehicles with no emissions and venues tucked below ridgelines where they won’t spoil the view. “The goal would be to leave the environment better than it is now,” says Carolyn Wallace Dee, manager of administration for Squaw Valley Ski Corp., a coalition board member who also serves as mayor of Truckee. “Yes, there’d be some inconvenience, but there are so many ways you can win from this.”

And, Kelly says, the Reno-Tahoe region has many of the strengths that would make it a contender. It has solid transportation, an array of venues and one-stop international air service. Its geography puts all events within about an hour’s drive (Sacramento, two hours down the mountain, could be used for demonstration events and as an air gateway). It’s close to a solid base of potential ticket buyers from San Francisco, Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

It also has more than 30,000 existing or planned hotel rooms in the Reno-Tahoe area, and 70,000 if you count the whole Sacramento metro. “Those numbers are higher than Salt Lake City had at this stage,” Killoran says.

The timing may be right, too. With the 2014 Winter Games in Russia and the contender cities for 2018 in Europe and South Korea, a 2022 Olympiad would be the first in 12 years in North America and the first in two decades in the U.S. Other potential contenders include Denver, other sites in the Rockies, perennial candidate Anchorage, upstate New York, Calgary and Quebec City.

The two-state approach adds to the potential complications of a bid, but also offers some advantages. California, Hartley says, could provide heavier snowfall, more companies as potential backers, more potential ticket buyers and a global air hub in San Francisco International Airport. Nevada has hotel rooms, Reno’s ‘can-do’ attitude and more relaxed environmental rules that could allow venue construction without the possible court fights spurred by the California Environmental Quality Act.

“It’s a challenge, but we know we’re going to have to (work together) to be successful,” he says.

And success could be lucrative. Kelly calls himself a skeptic on overblown claims of the economic impact of new stadiums and sporting events, but he’s run two U.S. Olympic Festivals and was president of the Goodwill Games from 1990 to 1996. He’s studied the numbers and says the Atlanta Summer Games of 1996 brought in about $4 billion in spending that would have otherwise gone elsewhere and added $187 million in incremental tax revenue.

“The challenge,” he says, “is to take all the elements we have and craft a compelling package. … It’s a matter of conveying the ‘why’ rather than the ‘how’” and peaking at the right time.

The local effort won’t lack for Olympian ambassadors. Organizers have reached out to dozens of Olympic athletes who live or train in the area.

“Of course I’ll help,” says Osvaldo Ancinas, who competed in Alpine skiing for Argentina at Squaw Valley in 1960 and moved there in 1963. He raised a family there with his wife, Eddy, who was a guide at the 1960 games and wrote about the 50th anniversary for The Atlantic magazine. “It would be wonderful to see the Olympics back in Squaw Valley. … I have nothing but the best memories.”

“In my head it’s a no-brainer,” says Jonny Moseley, a U.S. gold medalist in moguls in 1998 at Nagano, Japan, who trains at Squaw Valley and lives in Tiburon. “I’m sure there’s a boatload of fundraising to do, and we’d have a role in that.”

Nick Cunningham of Monterey was on a U.S. bobsled team in Vancouver and would love to see a track and training facility near Tahoe. He attended a coalition board meeting and got a look at one potential track site near Slide Mountain, northeast of Lake Tahoe.

“I got really excited about it,” Cunningham says. “2022 would probably be my last Olympic Games, so that would be a nice homecoming.”

Recommended For You

Own & Leisure

Major resorts change hands in the High Sierra

Spring weather has graced area ski resorts with abundance, dumping generous volumes of snow on the slopes for giddy guests.

Water Under the Bridge

A plan for Squaw Creek is a plan for jobs

Squaw Valley USA was once the premier ski resort of California and the world-renowned site of the 1960 Winter Olympic Games. But in the decades that followed, the resort’s managers focused on the mountain, and Squaw became eclipsed by other resorts that boasted hotel rooms and other amenities to capture business in the dry months.