The tiny town of Tórshavn, capital of the Faroe Islands, lays claim to having the world’s oldest parliament, dating back to the early ninth century. These days, its government buildings are housed in the old part of town, built by the Vikings in the 1400s, in small, red-painted buildings with thick grass roofs.

Earlier this summer, my wife and I flew from London to Copenhagen, one of my favorite cities in Europe, with its lively waterfront areas and its thriving arts and cafe scenes. We met up with two Danish friends there, and the four of us flew two hours northwest to the archipelago of moss-covered islands that jut out of the north Atlantic, hundreds of miles north of Scotland and east of Iceland.

It would be, I had realized sorrowfully earlier this year, the first summer in 21 years that I hadn’t traveled with one or both of my children. We have, together, covered large parts of the globe and visited dozens of countries. Now, however, my kids have both left home, and each have their own adventures to notch up. I could, I felt, either wallow in sadness at this state of affairs or, with my wife, chart our own course and go to places that we had never previously visited, using the strangeness of new locales to ask myself a series of questions on, broadly speaking, what it all meant. Hence a long summer of travels involving London, then the Faroe Islands at the front end, Southern France in the middle, and, for me and an old college friend, Tallinn, Estonia at the back.

The Faroes are a marvelous landscape of sheer cliffs, steep, greener-than-green slopes ornamented with waterfalls, hidden lakes and majestic fjords. When our plane was descending over the archipelago to land at the airport outside of Tórshavn, the pilot announced that this was the shortest commercial runway in the world and that to stop the plane before it careened off into the surrounding water, he would be sending the engines into reverse thrust. Nothing to worry about, he said; this was simply standard operating procedure in the Faroes.

Speckled around these islands, there are, every few miles, remote hamlets and even remoter crofters’ cottages — tiny, grass-roofed affairs that seem to stand outside of time. Presented with such a building, one can imagine what life was like half a millennia ago. By contrast, there are also fabulously complex road-tunnels under the Atlantic connecting the islands. Those are a true miracle of modernity and of human ingenuity.

Unless you’re a nesting puffin, it’s a harsh, weather-beaten corner of the world. In most hamlets one can’t even find a small café; but in Tórshavn, by contrast, there are several world-class restaurants, including, improbably, a Michelin-starred eatery named Ræst, where the chef and international staff offer up a spectacular 16-course taster menu utilizing seemingly every edible sea creature, mammal and species of vegetation on the islands and in the surrounding waters.

Ræst and a handful of other upscale restaurants build off of the reputation won by Koks, the first Faroes dining establishment to gain Michelin stars and one of the reasons the islands have become something of a tourist destination in recent years. In 2022, the owners relocated their eatery to Greenland to seed that island’s even more improbable rise up the world’s culinary ranks; but their legacy remains with the proliferation of high-end restaurants in the little town.

There are more sheep than humans on the Faroes. The latter, 56,000 of them, speak a unique language that, despite the islands being controlled by Denmark, is more akin to Icelandic, Old Norse or Old English than it is to modern-day Danish. They live in a political world that is formally tied to Denmark. But, unlike the mother country, in theory at least, so as to preserve the uniqueness of their culture, they are not part of the European Union. (In reality, however, since they have Danish passports, and since flights from Copenhagen to Tórshavn are considered domestic flights, there may be no effective mechanism to stop the freedom of movement and of trade that defines the EU, which could be why one sees so many people from a variety of countries working the restaurant scene of Tórshavn).

In different ways, people and places survive against the odds. How and why did the original settlers of the remote Faroes sail the storm-tossed North Atlantic in search of unknown islands, only marginally capable of sustaining agriculture, to populate? Truth be told, I don’t know. In some ways, the more I travel the more I realize how little of the human story and how small a part of the collective human psyche I really understand. And that humbling realization may, ultimately, be the best reason of all to continue traveling.

I’ve taught my children this as we travel — encouraged them to be curious, to journey the road less traveled. As I write this, my son is hiking in Central Asia; my daughter has, in the past year, visited Vietnam, Hong Kong, South Korea and Japan. They have, in the best way possible, flown the nest — and while I am sad they are not traveling with me, I dance for joy when I think of what they will see and hear and experience on their own adventures in the years to come.

–

Stay up to date on business in the Capital Region: Subscribe to the Comstock’s newsletter today.

Recommended For You

Welcome, Fall, and All Your Beauty

The Last Word: Comstock's editor remembers East Coast autumns

We were driving through a small town in northern New Jersey one October when we saw a huge pile of leaves someone had raked into a mound. We looked at each other with big smiles, pulled over, ran with abandon and jumped into that leafy patch. No, we weren’t schoolgirls having fun, but three women in their 50s reliving their childhood.

The Big Commitment: On Friendships, Aging and the Sacred Silliness

For our Last Word essay column, Comstock's former associate editor reflects on friendship

Following an uncomfortable pause after the officiant asked if

anyone knew a reason why these two shouldn’t be joined in

matrimony, Monty, a comedian, stood up and loudly objected. Once

the giggling started, the entire crowd realized we were in for

another performance.

The Heart of a Campfire

Remembering generations of sleeping under the stars in California

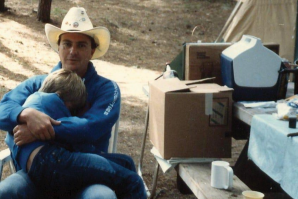

Like my father before me, I taught my son to build a campfire the

old-fashioned way: with balled-up paper under kindling, under

twigs, under larger sticks, all fastidiously layered beneath

three logs wigwammed in the center. It was a thing of beauty. We

stood back in proud appreciation of our handiwork before striking

a match in a solemn generational ceremony.

My Father’s Legacy: Untamed Joy

Contributor Marie-Elena Schembri shares memories of her father for our monthly personal essay column

As a young girl, I thought my dad was the funniest, smartest, most handsome man in the world. He had many wonderful and endearing qualities, but he was a complicated man. He was an alcoholic and carried a depth of grief, shame and anger that often made him hide the best parts of himself.