It should come as no surprise that when the California Legislature recently began the process of divvying up proceeds from the state’s cap-and-trade auctions, a cavalcade of local officials, community activists and lobbyists rushed to Sacramento, with hands out.

Billions of dollars burning a hole in the state’s pocket has that effect on people, and the competition is fierce. Appeals from advocates to fund pet projects were spread over two days in late August, in windowless rooms before sometimes distracted officials. The requests are for cash for electric vehicles, to create green spaces, even for machines to cut pollution from cow manure.

Brevity is prized in this legislative equivalent of speed dating, which plays out in front of committees in the Senate and Assembly. There’s scant time to make the case for your cause. Talk too much, and you risk irritating the panelists. Nobody wants the stink eye from the people with the purse strings.

“Thirty to 60 seconds is the sweet spot,” said Amy Vanderwarker, co-director of the California Environmental Justice Alliance, who sought millions in funding for programs that help people in low-income communities adapt to climate change with solar panels and weatherproofing.

For Vanderwarker and the dozens of others who filed through, there’s a lot at stake.

Nearly $5 billion has flowed into the state’s unique Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund since 2013. The money is raised when the state auctions permits to pollute, part of California’s program to cap planet-warming emissions. The account fluctuates with the carbon market.

A big chunk of the revenue each year is spoken for, set aside for the state’s high-speed rail plan, affordable housing and a host of transit projects. The discretionary portion amounts to about 40 percent of the total and must go toward projects that lower greenhouse gas emissions or assist low-income areas.

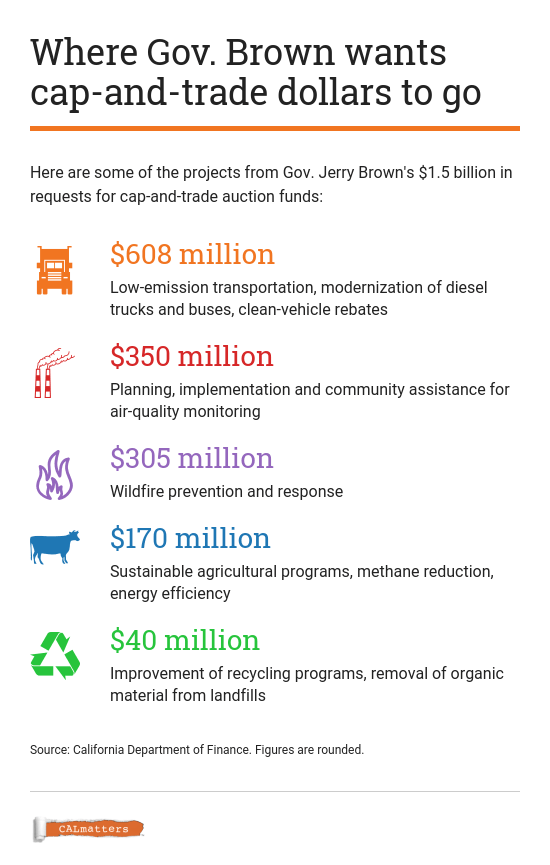

The feeding frenzy this time was for less than $1 billion, and balancing the account won’t be easy. Lawmakers’ wish lists total $3.5 billion, the governor wants $1.5 billion, and the supplicants came in seeking more than $2 billion. There’s list overlap—many of the projects are the same, but they cannot all be fully funded.

At the outset of the Senate hearing, Bob Wieckowski, a Fremont Democrat who chairs the budget subcommittee, attempted to lower expectations for those who saw a bottomless well. There’s $842 million for use now, he told the audience, so work with that when making requests.

There is an art to queuing up for a shot at the pot of gold. Better to be an earlier speaker when attention spans are fresh, or at the end, to get the last word?

Ronald Hughes, director of the California Vanpool Authority, employed the early-bird strategy: “Sit toward the front” during the opening portion of the proceedings, he said—prime placement to snag a spot at the front of the line.

To be pressed cheek by jowl with high-priced lobbyists and speak before harried legislators “is always intimidating,” Hughes said. “I’m from a small town, Hanford. You’ve got to stand there and have your ‘elevator speech’ ready. It’s uncomfortable.”

Hughes’ “ask,” as the requests are known, was among the day’s most modest: $6 million to fund the statewide system of vans that ferry farm workers to and from the fields, reducing traffic and keeping heavily polluting jalopies off the road.

Over in the Assembly, Richard Bloom, a Democrat from Santa Monica, chaired the hearing. “Remain orderly and don’t elbow anyone out of the way,” he announced.

Max Podemski, planning director for the community group Pacoima Beautiful, was preparing an ask for the first time and wasn’t ready for the rush when the public was welcomed to the floor.

“I was sitting there, and all of a sudden there was a stampede” to the microphone, Podemski said. His group wants $20 million for greening and beautification of Pacoima Wash, a 10-mile flood-control channel in the San Fernando Valley. The funds would provide park space, a bike path and connections to public transportation.

The jockeying can get testy. There was much harrumphing when a delegation of uniformed fire chiefs, resplendent in brass-buttoned and beribboned uniforms, broke from protocol and cut to the front of the line.

After two and a half hours, the last speaker in line, Terry McHale, a lobbyist for a state firefighters union, drew appreciative chuckles as he acknowledged the ordeal.

“Not since my large Irish Catholic family would line up for allowance have I been in such a long line of people with their hand out,” McHale said. “Being the smallest in my family, I was the last in that line, too.”

Back in the Senate, the knot in Wieckowski’s tie was slipping south and the line of those still waiting to speak had no end in sight.

Eventually, everyone had their say, if not their money.

Lawmakers will vote on the entreaties—they typically favor transportation, forestry, agriculture and urban “greening” projects—before adjourning for the year on Sep. 15.

CALmatters is a non-profit journalism venture dedicated to exploring state policies and politics.