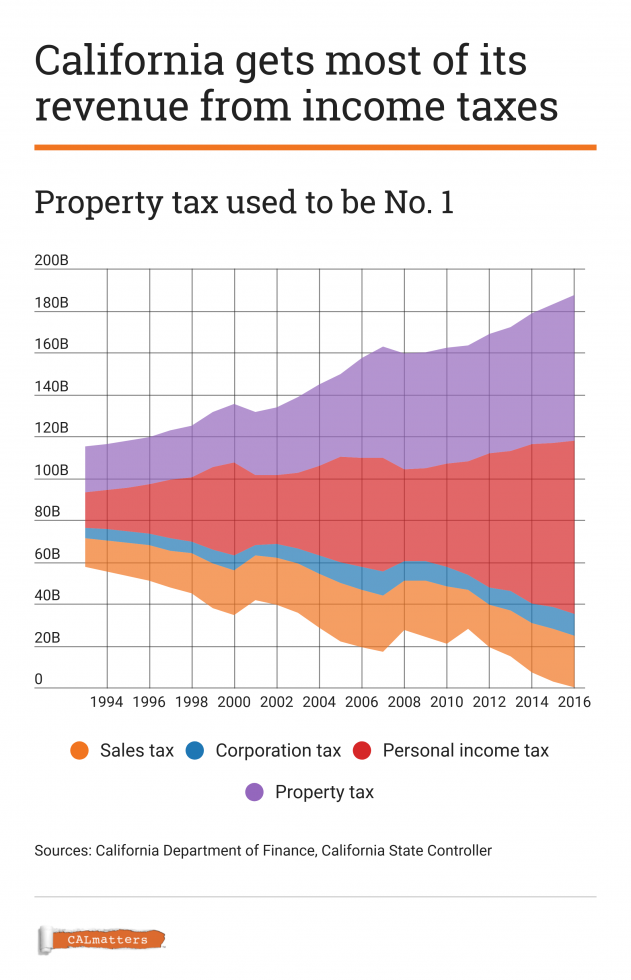

California’s major revenue sources have shifted over time. Until 1995, the biggest was property taxes. Today, it’s personal income taxes.

And California ranks fairly high in overall taxation: 10th highest both per capita and as a percentage of personal income, based on the latest available data from the U.S. Census.

In 2015, state and local governments collected $228.7 billion in taxes, including property, sales, personal and corporate income levies and a few others, according to the census. That’s in a state with more than 39 million residents and personal income worth nearly $2 trillion that year.

California’s taxes have risen in ranking partly because of voter-approved increases. In November 2012, the state passed a temporary hike in sales taxes of 0.25 percent and raised personal income taxes on the rich. Four years later, voters extended the income tax increase for 12 more years.

Gov. Brown and lawmakers also approved a 12-cent gas-tax hike in 2017 to help raise $5 billion a year for aging infrastructure. The measure includes increasing the annual vehicle fee between $25 and $175, depending on the vehicle’s value.

Of course, there’s some variation:

- California has the highest statewide sales tax rate, at 7.25 percent, and is ranked ninth by the Tax Foundation in combined state and local sales tax rates.

- The state has the highest personal income tax rate for its wealthiest. It’s 9.3 percent for those making $53,000 to $269,000 and 13.3 percent for those making $1 million or more.

- California has below-average property taxes due to Proposition 13, the famous 1978 measure that capped increases to no more than 2 percent a year. The Tax Foundation ranked California 35th in the nation in taxing owner-occupied housing.

In its willingness to tax the rich, the state has become more reliant than ever on personal income taxes.

Individual wages and business income as a measure of the overall economy aren’t terribly volatile. But California’s income taxes are over five times more volatile than personal income because they also include investment gains, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office. The state taxes capital gains, partnership income and dividends, interest and rent—areas where the highest-income taxpayers derive most of their money.

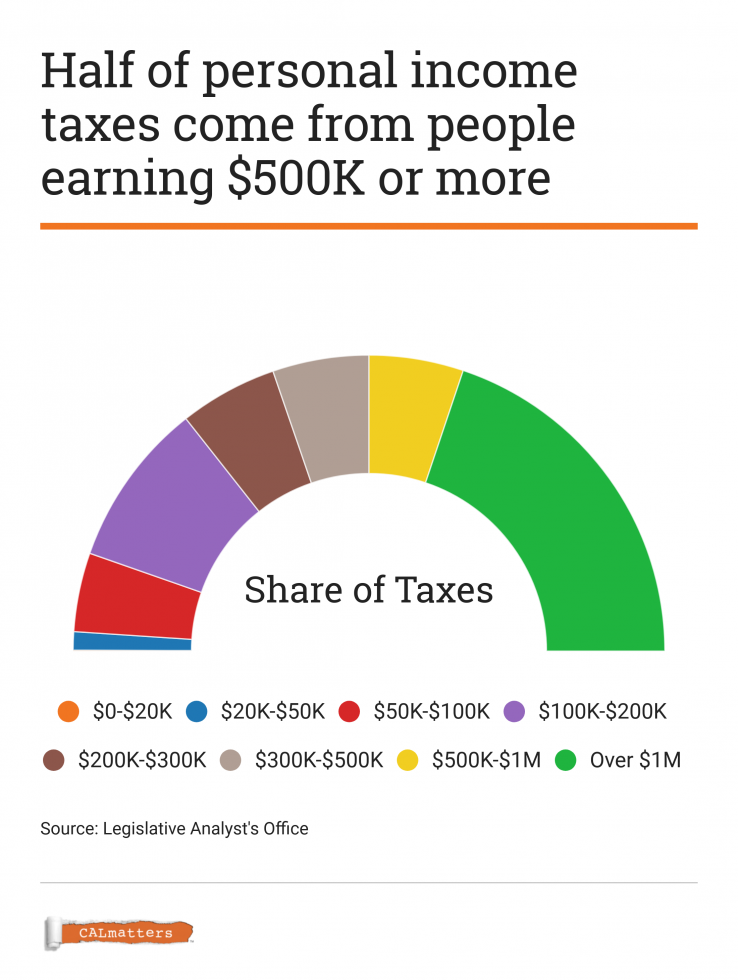

The result? Millionaires and billionaires contribute a disproportionate share of tax revenue—so much so that the top 1 percent of taxpayers now generate half of personal income tax receipts.

According to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, half of the state’s personal income tax revenue comes from those making $500,000 or more. Conversely, households making $50,000 or less make up nearly 60 percent of tax filings but make up just 2 percent of revenue.

This volatility can mean huge cash infusions in good times. For example, when Facebook went public in 2012, top employees such as company founder and chief executive Mark Zuckerberg, along with early investors, plumped state coffers with an estimated $2.5 billion, which arguably prevented some school funding cuts amid a $16 billion budget deficit.

The opposite is true in bad times.

During the Great Recession, the state faced multiple years of multibillion-dollar deficits, including a shortfall of $39.5 billion in 2009, as fallout from the housing and economic crisis.

The California Teachers Association estimates 30,000 teachers were laid off during the recession. When the state ran low on cash in 2009, it issued IOUs, mostly to taxpayers waiting for their tax refunds. The state cut benefits for the poor, such as dental coverage for those on Medi-Cal. And state workers, along with many local government employees, were forced to take furloughs, hitting working-class families.

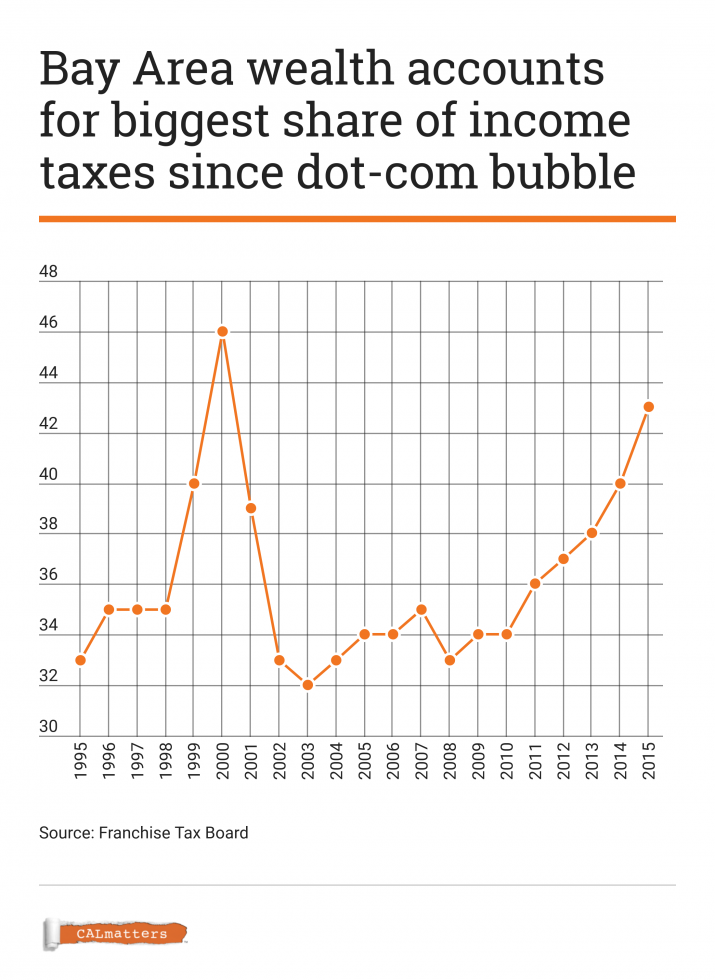

The tech sector has an outsized influence on California’s tax volatility. According to the legislative analyst, the nine counties that make up the San Francisco Bay Area contribute 40 percent of personal income taxes but are home to only 20 percent of the state’s population.

That marks Silicon Valley’s largest share since 2000.

It’s why California budget watchers pay attention to stock-market gyrations. When the Dow experienced two 1,000-point plunges in one week in February, it triggered anxiety over state revenue.

There’s a saying that when Wall Street catches a cold, California gets the flu.

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics. This reporting project was produced in partnership with the Ravitch Fiscal Reporting Program at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism.