In one of his first official actions, Gov. Gavin Newsom has directed that state agencies, including the one that oversees Medi-Cal, negotiate as a block to demand prescription drug makers lower their prices.

The move will make California the nation’s largest negotiator against pharmaceutical companies, and could become a model for other states—if it works.

“Right now, with all the gridlock in Congress, we are seeing quite a bit of state action on prescription drug pricing—and we hope that advances as much as it can until we can see some change in Congress,” said Peter Maybarduk, who specializes in medicine access at Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy group based in Washington, D.C.

“California government has power,” he continued. “It is a large enough economy and large enough state to influence pharma behavior and dictate terms.”

It’s such an attractive idea that it seems to have united the progressive Newsom with his political nemesis, President Donald Trump. Both have espoused the wisdom of the government consolidating its massive purchasing power so it can bargain hard with drug companies and thus cut the best deal for taxpayers.

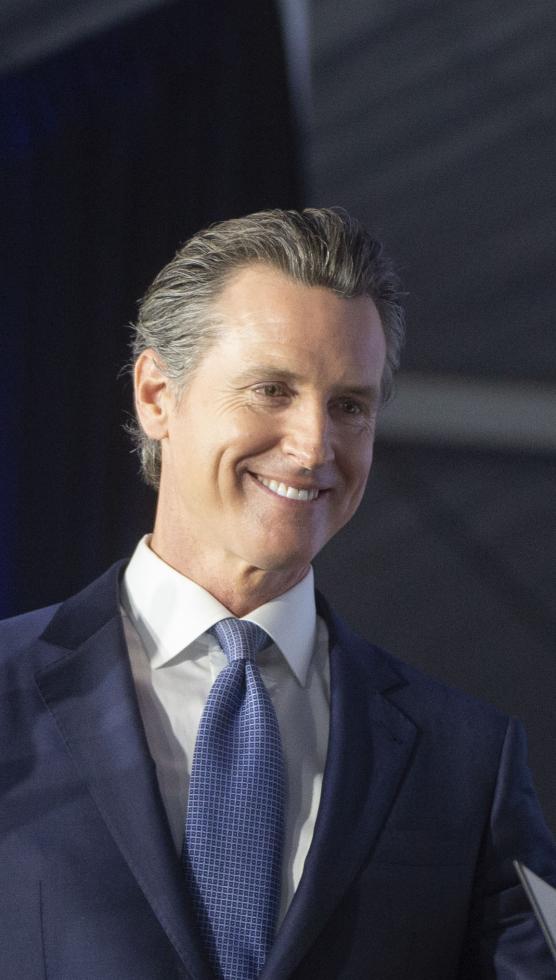

Gov. Gavin Newsom takes the oath of office. Photo for CALmatters

by Randy Pench

Trump campaigned on the notion of harnessing the federal government’s bargaining power to reduce drug prices for programs like Medicare, but the idea went nowhere because it’s prohibited by federal law. Congress specifically barred the federal government from negotiating Medicare drug prices—a restriction defenders describe as free market protection and critics deride as a giant pacifier to Big Pharma.

Still it remains a simple and appealing idea in a nation confronted by rapidly rising prescription drug costs. A recent Harvard/Politico poll found the number one priority for voters for the new Congress is reducing the cost of prescription drugs.

There’s a reason it’s top of mind. A study released this month in the Journal of Health Affairs found that the cost of brand-name drugs rose each year between 2008 and 2016—by more than 9 percent for oral medicine and more than 15 percent for injectable medicine. Specialty drug prices soared even higher each year.

In his executive order, Newsom said California has seen prescription drug prices rise 20 percent annually since 2000—and that the 25 most expensive drugs account for half of the state’s spending on pharmacy costs. So far Newsom’s office has not released any estimates of how much it expects the new bargaining plan to save.

“We will use both our market power and our moral power to demand fairer prices for prescription drugs,” Newsom said during his inauguration speech Monday.

That same day he told the state’s Department of Health Care Services to begin negotiating the purchasing of prescription drugs for all 13 million recipients of Medi-Cal, the state’s health care system for low-income patients. Currently the state only represents 2 million of them while the rest are on managed health plans that negotiate their own drug rates.

“The governor is the only one that can do this, he is the only one that can force everybody to the table,” said Democratic Assemblyman Jim Wood of Healdsburg, who heads the state Assembly’s health committee.

He said the consolidated bargaining power is vital to address skyrocketing drug prices. With nearly one in three Californians on Medi-Cal, and its budget of $250 billion, even small savings could be significant.

“The savings we’ll be able to enjoy from less spending on prescription drugs,” Wood said, “will help offset some of the additional costs that we’re going to be incurring to expand coverage for other people in California.”

Massachusetts was the first state to enact a “bulk Rx buying plan” in 1999. Eventually states started joining forces, and now there are five bulk buying programs that include multiple states, with some reporting significant savings. Three of those are focused on buying drugs for Medicaid recipients, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

The oldest one, focused on Medicaid pooling, was created in 2003 with four states and has now grown to 10, including Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New York and North Carolina. It represents 3.8 million Medicaid recipients—still less than a quarter of the Medi-Cal recipients California will be bargaining on behalf of.

In its last session, the California Assembly approved a bill that would have created a prescription drug bulk-purchasing program for the state, but it was then held by its sponsor, San Francisco Democratic Assemblyman David Chiu. His office cited a lack of support from then-Gov. Jerry Brown. And nearly two decades ago—in another effort to decrease drug expenses—the state authorized the Department of General Services to buy prescription drugs for state or local agencies through a bulk purchasing program, but the program hasn’t been used much.

Newsom’s new order aims to reduce the amount California taxpayers now pay to provide medications to Medi-Cal recipients and state employees. The governor’s plan calls for eventually giving private employers the option to join the consolidated purchasing block, although how that would work is still vague.

As for the expected drug industry opposition, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America said it’s reviewing the proposal. “We welcome the opportunity to work with the governor and his administration on comprehensive solutions to the problems patients are facing accessing and affording their medicines,” said spokeswoman Priscilla VanderVeer.

Gerald Kominski, senior fellow at the UCLA Center for Health Policy, lauded the idea of using market power to obtain the lowest prices possible, but predicted that drug makers would unleash a campaign against it inside and outside of California.

“They will start running ads that are going to scare people—that if you are on Medi-Cal you are no longer going to get this drug or this drug,” he said. “There will be dark music and maybe a doctor in the scene shaking their head no saying you are no longer eligible for this or for that.”

For the health plans that currently serve the majority of Medi-Cal patients, efforts to get better prices are welcome, said John Baackes, CEO of LA Care Health Plan. With 2.5 million Medi-Cal patients, it is the largest Medi-Cal managed plan in the state.

“We are supportive of investigating the idea, because logically it says if the state is negotiating for 13.5 million people they can do a lot, maybe more than what we can do for 2 million people,” he said. “It’s worth it to see if it will produce better pricing.”

But the details are going to matter, Baackes said. There has been no information yet on how it will be administered or how the state would handle customer service.

Even California, with its newfound, super-sized buying power, can only bargain so far. Larry Levitt, senior vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, called Newsom’s approach “promising.” But he noted that the state can’t walk away from a negotiation because it has an obligation to make sure that Medi-Cal recipients can access the drugs they need.

“Leveraging the purchasing power of the state is certainly a smart move,” said Sacramento Democratic Senator Richard Pan, chair of the Senate Health Committee. But he added a caveat: “We want to make sure it’s done in a way that ensures that people have access to the medication they need.”

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.