One month from the Illinois primary, GOP Congressman John Porter decided something needed to be done about an upstart candidate named John Cox.

It was early 2000 and Porter had opted not to seek re-election in his suburban Chicago district. Cox, a little-known millionaire with the backing of many North Shore anti-abortion advocates, was coming on strong in the polls. With the vote liable to split unpredictably across 11 candidates, Cox could win the primary. But Porter was convinced he would lose in the general.

Cox “was a pretty conservative guy and didn’t seem appropriate for my district,” recalled Porter, who reneged on a pledge not to get involved and endorsed his former chief of staff, who won.

For Porter, it was the smart political move. To Cox, this was the corrupt political machine turning against him. The takeaway was clear, Cox would later write in his book Politic$, Inc.: “Never trust any politician.”

Even so, John Cox spent the next two decades trying to become one.

In nearly a half-dozen campaigns for Congress, U.S. Senate and yes, even the presidency, Cox has embraced the persona of the anti-politician assailing a corrupt establishment. The strategy hasn’t worked yet. But as he seeks to become governor of California, the 63-year-old lawyer, accountant and investment manager is hoping 2018 will be different.

It’s his most successful electoral gambit to date. Before the June primary, Cox, a businessman from tony Rancho Sante Fe, snagged the endorsement of his career—the occupant of the White House. Surprising, given that Cox voted for Libertarian Gary Johnson, not Donald Trump, a man who rarely overlooks a slight. (Cox has since said he regrets doubting Trump and has been “pleasantly surprised by our president.”) Likely the president was swayed by congressional Republicans, who coalesced around Cox believing that he had a better shot at making it onto the general election ballot than his more Trumpian Republican rival.

It would be difficult for any Republican to win the governor’s seat in November, the thinking went, but at least Cox would gin up turnout for endangered GOP members of Congress.

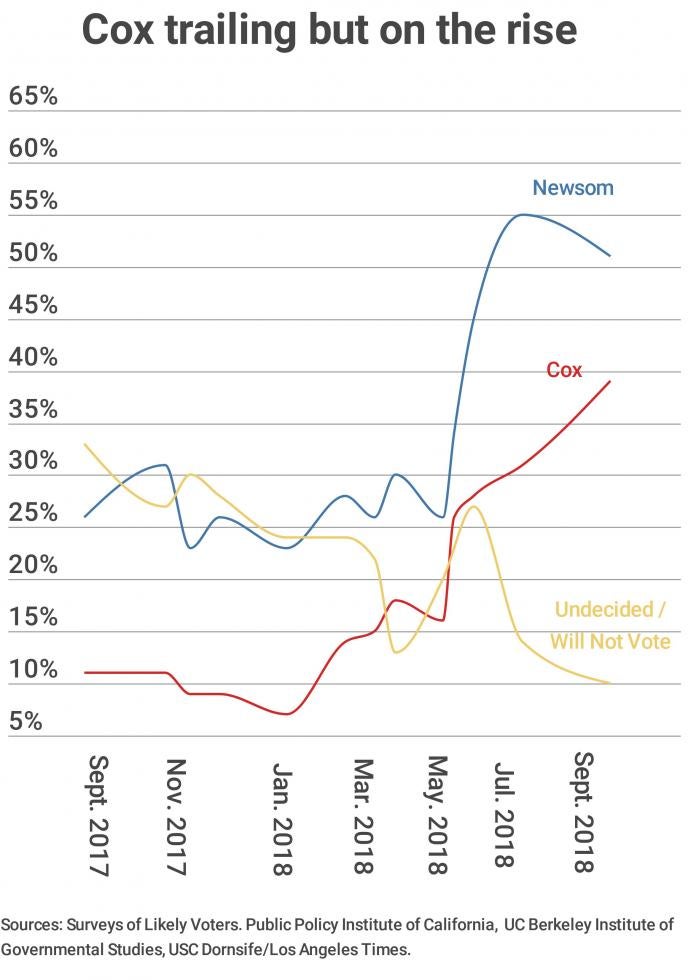

So unlike prior campaigns, where he’s often brought up the rear, Cox emerged as one of the top two finalists and now faces Democrat Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom, who from resume to hairdo looks every bit the consummate politician.

In short, Cox has finally become a serious contender. Maybe.

His new success speaks as much to the diminishment of the state Republican party as anything, said Dan Schnur, a former GOP consultant and University of Southern California professor.

“It’s not John Cox’s fault that the California Republican bench is so empty, but he certainly took advantage of the opportunity that the party’s plight presented,” he said.

Trim and tan, with a shock of white hair and Barry Goldwater thick-rimmed glasses, Cox is earnest and Midwest Nice, if periodically exasperated that not everyone sees the world as he does. Above all, he’s strikingly optimistic—the kind of optimism you would expect of a working-class kid-turned-millionaire, of a Democrat-turned-Reagan Republican, and of anyone who hopes to be California’s first Republican governor in over a decade.

Born on the south side of Chicago, his biological father abandoned the family. When he was 3, Cox’s mother—a Jewish, Kennedy-loving public school employee with a degree from UC Berkeley—moved to working-class suburbs south of the city. Cox took his stepfather’s last name.

In high school, his lengthy list of extracurriculars befit a kid who might one day run for office: president of speech club and in the thespian society, and on the basketball and football teams—not a player but team manager.

“He would tell you if he was upset with something or if he agreed with you or didn’t agree with you,” said former classmate Steve Bithos , who recalls that Cox was smart and good-natured but bullied in school, something the candidate has spoken about. “He was tiny and he looked very young.”

Cox went on to earn a political science degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago—in two and a half years “because I was paying for it.”

He attributes his GOP conversion to Ronald Reagan and conservative economists at the University of Chicago, and his professional experience once he earned a law degree and started his own practice helping businesses navigate regulations and a labyrinthine tax code.

Around this time he married his first wife and joined her church. He remains a Catholic today and cites his faith when discussing his opposition to both abortion and the death penalty. (Two decades and three children later, that marriage, he said, ended in an annulment. He married his current wife, Sarah, in 2002; they have a daughter.)

In the 1990s he helped the Japp family reacquire their family potato chip company, Jays Foods, and manage it back into profitability. Cox cites it on the campaign trail—the story of a turnaround artist the likes of which Illinois, the United States and California so desperately need. But as the Los Angeles Times reported, Cox paid a $1.7 million settlement to the Japps for alleged self-dealing while working as their advisor. He has said he settled a “frivolous lawsuit” to rid himself of the trouble.

When he ran for Congress in 2000, and for U.S. Senate the next election, the reaction of the Illinois Republican establishment was mixed. Former Cook County GOP chair Chris Robling described Cox as “independent, single-minded, maybe kind of iconoclastic…“I think he was frustrated with the milquetoast variety of Republicanism.”

In 2004, Cox once again ran for the U.S. Senate, and later for the more modest position of Cook County Recorder of Deeds. He lost.

Whenever he has been asked the obvious—Why not start with something a little less ambitious?—he simply replies that he doesn’t want a career in politics and therefore doesn’t have time to work his way up.

Evidently not: in 2006, he ran for president.

Steve Kush, who briefly managed that campaign, described him as “an incredibly sensible guy.” But the odds were not lost on Kush.

“You have some long-shot candidates in every presidential cycle and, you know what, they serve a purpose,” he said. “They hold the feet of the big money guys to the fire.” But he said Cox didn’t see it that way: “You don’t spend millions of your own dollars to not believe you can catch fire.”

How does “an incredibly sensible guy” conclude he should run for president despite having absolutely no national name ID?

The conservative Weekly Standard summed up that conundrum in its profile “The Sane Fringe Candidate.” It described Cox as laboring “under the mistaken impression that presidential campaigns are about ideas”—a serious man trying in vain to be taken seriously.

Exporting his aspirations westward, Cox bought a house north of San Diego and began funding bold initiatives that garnered him intermittent, if bemused, coverage.

Four times he floated his idea to remedy the corrupting influence of political donations: Divvy up the state into thousands of pint-sized districts, ballooning the number of elected state legislators to roughly 12,000.

“I’m a voice in the wilderness, maybe,” Cox said. “I’m no nut case.”

Or there’s the 2016 “California is Not for Sale” proposal, which would have forced legislators on the Senate and Assembly floor to wear clothing emblazoned with the logos of their top funders—Nascar-style.

In his current bid for governor, Cox has flirted with the idea of abolishing the state income tax, supports private school vouchers and endorses Trump’s border wall.

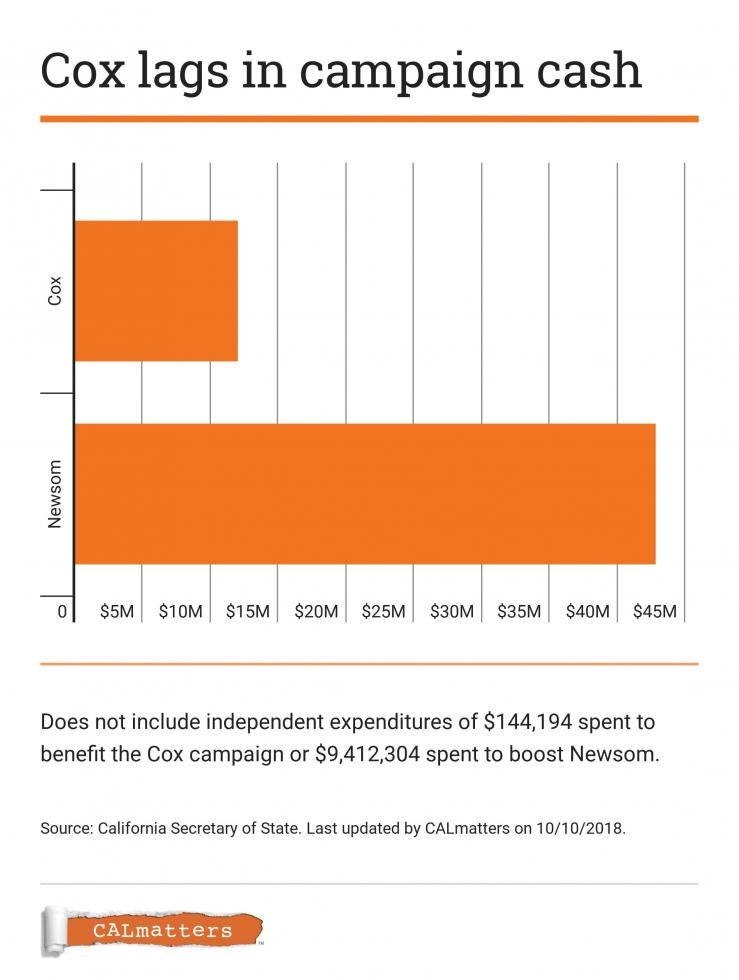

But he’s tethered himself to Proposition 6, the effort to repeal a gas tax hike, which like Cox is polling only in the high 30s. And he’s donated $5.7 million to his campaign, nearly half his total haul.

“I’m gonna have fun turning around this state,” Cox told CALmatters.“I’m looking forward to building a team of business people like myself that will come in the government and re-engineer it and reinvent it.”

Vintage Cox—but a perception not widely shared.

“Any Republican running for governor of California has to know he’s likely going to lose,” said Jason Roe, a GOP political consultant in San Diego. Then again, he acknowledged, Cox “isn’t dissuaded by what the conventional wisdom is.”

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

![By Tommy Lee Kreger (John Cox-6) [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](/sites/main/files/imagecache/carousel/main-images/12john_h._cox.jpg?1577874530)