Minutes before President Donald Trump landed in California on March 13, the most powerful politicians in the state sent out a public statement that had nothing to do with him and would garner little attention. The announcement from Gov. Jerry Brown and legislative leaders said that due to recent devastating fires and mudslides, they would work together this year to “make California more resilient against the impacts of natural disasters and climate change.” Among the issues they promised to address: updating liability laws for utility companies.

The innocuous-sounding statement belies a controversial idea: that Californians could eventually have to pay more for electricity because of last year’s wildfires.

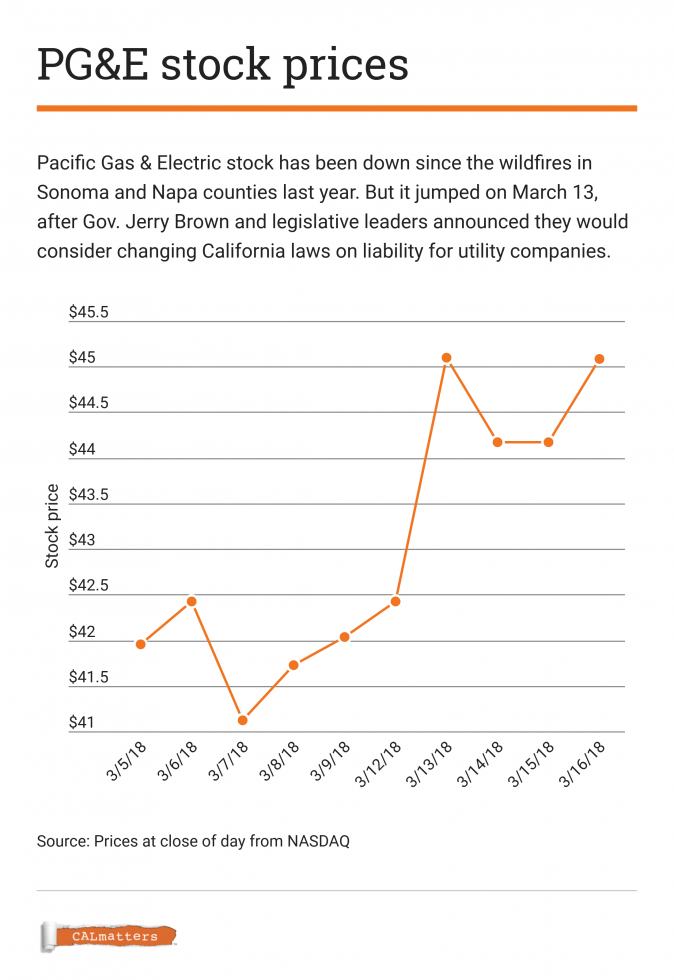

With the state’s gaze trained on Trump visiting the prototypes of his border wall, the announcement went largely unnoticed in California. But it landed with a splash on Wall Street. Pacific Gas & Electric’s stock price, which had been falling since October’s wine country fires, immediately shot up. By the time trading closed, Barron’s declared it the day’s “hot stock.”

“PG&E was helped by news that California may update its liability rules and regulations for utility services,” said Barron’s, a publication for investors.

The politicians’ announcement that triggered the stock price increase was the product of months of lobbying by California’s three investor-owned utility companies. The businesses are worried about possibly being held liable for billions of dollars in damages stemming from last year’s catastrophic fires in northern and southern California. Investigations to determine the causes of the fires are still under way, and at this point no blame has officially been assigned to the power companies.

But recent rulings in court and at the state Public Utilities Commission have set precedents that make the big utilities—and their investors—nervous. Under the legal doctrine known as “inverse condemnation,” courts have ruled that private utilities are responsible for any damages traceable to their equipment—even if they were not negligent in maintaining it. Late last year, regulators decided that the San Diego Gas & Electric company could not pass that cost on to their customers, after the utility asked if it could raise rates to cover liability from wildfires in 2007.

Financial markets see the potential risk. Stock prices dropped for Southern California Edison after the December wildfires in Santa Barbara and Ventura counties, as they did for PG&E following the autumn blazes in Napa and Sonoma counties. Credit agencies have been lowering PG&E’s bond ratings.

So the power companies’ lobbyists have been pounding the hallways of the state Capitol, asking legislators to change the “inverse condemnation” law. They argue that it shouldn’t apply to them—or if it does, they should be allowed to raise rates to cover their costs. That raises an expensive and emotional question: Who should pay for wildfire damages if the power companies are liable, their stockholders or their customers?

The utilities are big political donors and have a lot of sway in a Capitol dominated by Democrats. The three companies have given at least $12.5 million to California political campaigns since 2013, including more than $2.5 million to the state Democratic Party.

They also play a significant role in realizing California’s ambitious climate-change goals by developing clean energy infrastructure, so environmental progress could be at stake if they go bust. On the other hand, Californians—who already pay 50 percent more for electricity than residents in the rest of the country—would see their bills jump even higher if the power companies are allowed to pass the liability costs on to their customers.

“If the utilities get the governor and the Legislature to change the liability rules, then what stake will they have in the game? There’s no reason for them to use best practices, to act responsibly, because they’re going to get bailed out,” said state Sen. Jerry Hill, a San Mateo Democrat.

Hill is a frequent critic of utility companies and thinks the current system is working well to protect residents from bearing the costs of liability. He says the utilities are trying to cast the problem as fallout from climate change so they can put the costs on customers instead of cutting into their profits.

Legislation to change the current liability rules has not yet been introduced, but the issue is one of several wildfire-related bills that will likely dominate the Capitol in the coming months. Gov. Brown and lawmakers also pledged to tackle problems with the emergency response system, availability of insurance for homeowners in risky areas and forest-management practices.

“The northern California wildfires came about from an extraordinary confluence of events. It’s too early to make any assumptions about liability,” PG&E spokeswoman Lynsey Paulo said by email.

She added that if the company is found liable under the “inverse condemnation” law, it would argue that costs should be “shared by all customers.” Paulo did not have an estimate on how much that might raise customers’ electricity bills.

Eugene Mitchell, vice president of San Diego Gas & Electric, said the utilities have asked state leaders to change the liability rules because wildfires and other natural disasters that come with a warming planet are creating a “new normal” for their business.

“This isn’t about our stock prices. If you have to pay more money for insurance to protect your customers, that is a higher cost for them,” Mitchell said.

“Building the green projects the governor envisions—more (energy) storage, more renewables—all that comes at a higher cost if you are viewed as being a risky investment due to these climate-change challenges.”

Legislators who joined Brown in signing onto the announcement didn’t lock themselves into any specific change in liability laws.

“We don’t know what the solution is going to be,” said a key legislative staff member who requested anonymity to talk candidly about behind-the-scenes negotiations.

“But we said, ‘We will send a signal to the market so Wall Street will know that we are going to take this seriously, that we are going to tackle this issue without predetermining what the outcome will be.’ ”

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.