A 1994 blockbuster among the MBA set, the book is a series of case studies on how some of the world’s leading corporations made it big. And it says a lot about the 51-year-old Democrat who polls say is most likely to become California’s next governor.

Gavin Newsom has a book that he says every Californian should read: Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies.

A 1994 blockbuster among the MBA set, the book is a series of case studies on how some of the world’s leading corporations made it big. And it says a lot about the 51-year-old Democrat who polls say is most likely to become California’s next governor.

Yes, Built to Last speaks to Newsom’s private-sector roots in the San Francisco wine business. And it’s full of the sort of TED Talk-ready neologisms and mantras that Newsom sprinkles throughout his speeches—and distributes in spiral-bound motivational booklets to his employees.

But the book is also an obvious choice because of one of its central insights: visionaries need a “Big, Hairy Audacious Goal”—a BHAG. “Like the moon mission, a true BHAG is clear and compelling and serves as a unifying focal point of effort,” the book explains. “People like to shoot for finish lines.“

Newsom likes to shoot for finish lines too.

“I’d rather be accused of (having) those audacious stretch goals than be accused of timidity,” he said. “Because I just don’t think the world demands timidity.”

He rose to prominence as San Francisco’s new mayor in 2004, when he presided over the first same-sex weddings in the country even while acknowledging his actions violated state law. It was an unprecedented move that the state Supreme Court rebuked as fomenting legal anarchy, but it was vintage Newsom, gambling correctly that same-sex marriage would eventually became the law of the land.

Now campaigning for the governorship, he has proposed remaking California’s healthcare system, its housing market and its early childhood education system in ways that seem both revolutionary and daunting.

“He thinks creatively about policy and enjoys following ideas where they go rather than prejudging them as unrealistic,” said Keith Humphreys, a Stanford psychology professor who co-led with Newsom the state’s committee to study marijuana legalization. “He inevitably spends some time thinking about things that are never going to happen, but it also means that he is sometimes able to push beyond what most people consider a possible policy.”

Critics call him starry-eyed—or worse. Over the years, Democratic and Republican foes alike have called the made-for-Hollywood politician a “narcissist,” a credit hog, a “snake oil salesman” and a “vapid pander bear.”

But no one could accuse him of failing to think big.

Newsom attributes his outside-the-box thinking to his dyslexia, calling it “the greatest thing that’s ever happened to me” —and not just because he credits his inability to use a teleprompter for his famously sharp memory and oratorical skills.

“There’s a creative energy to our approach,” he said of those with the disability. “I’m willing to take risks.”

He wasn’t always so sanguine. As a kid, Newsom bounced around schools in San Francisco before his mother moved the family to Marin County. Even there at Redwood High School, he recalls, he could barely read or write and he attended speech therapy to overcome a severe lisp. He got into Santa Clara University on a baseball scholarship, but barely graduated.

Gavin Newsom, with his little sister, Hillary, recalls being

raised by a single mother who struggled, and a sometimes distant

father with rich connections. Photo via Gavin Newsom

Newsom bristles at the suggestion (made often) that he is the product of privilege. His mother, Tessa Menzies, was 20 when he was born, and divorced Newsom’s father, William, a few years later. She largely raised Gavin and his sister by herself, working as a legal secretary, a waitress, a bookkeeper, then finally a realtor. According to Newsom, she took in foster kids for extra cash.

“He is a working class guy who has worked really hard with his bare hands, with a phenomenal support group,” said Geoff Callan, Newsom’s brother-in-law.

But that’s one hell of a support group. Newsom may not have grown up with money and power, but he was raised in power’s orbit, spending the odd weekend brushing shoulders with the titans of the Bay Area Democratic Party—Jerry Brown, Willie Brown, John Burton.

His grandfather worked on the political campaigns of Gov. Pat Brown and President Truman. Newsom’s father was the legal fixer for oil scion-turned-composer and philanthropist Gordon Getty. He later became a judge, appointed by his pal, Gov. Jerry Brown.

“Politics was a way of connecting with him,” Newsom said of his father. “In high school, getting him to come to a game would be one of the biggest days of my life.”

When then-Mayor Willie Brown appointed Newsom to the San Francisco Parking Commission in 1996 and then the Board of Supervisors at the suggestion of Burton, William Newsom took credit: “It was based on Burton’s friendship with me,” he told a reporter in 2003. “Besides, they needed a straight white male on the board.”

That powerful network has followed Newsom ever since. As the Los Angeles Times detailed, eight Bay Area families have jump started his political ambitions at every turn. That includes, most notably, the Gettys, who also provided seed money for Newsom’s business career. His first enterprise, PlumpJack Wines, was named after one of Gordon Getty’s operas. Since then, Newsom has gone on to found or co-found nearly two dozen ventures—wineries, restaurants and hotels—almost always with a little Getty help.

“Gordon has been a huge supporter of mine and I’m humbled by his believing in me,” said Newsom. That moral support, he insists, is “so much more potent and powerful than the investments,” which he says make up a small fraction of the total.

His critics aren’t buying it. John Cox, his Republican candidate for governor, has dubbed Newsom California’s “Fortunate Son.” It’s one of several similarly unflattering nicknames that Newsom has picked up, including “Prince Gavin” and the “heavily-lacquered lefty-sun-God mayor of San Francisco.”

Earlier this year, Sacramento Bee columnist Marcos Bretón labeled Newsom the “the living embodiment of privilege.” The column assailed not only his good fortune, but also his ability to skate by lapses that would have tanked less connected, rich, white, male, or handsome candidates.

The most famous such lapse: Newsom’s well-documented affair with his appointments secretary (and the wife of his then-campaign manager) in the mid-2000s. When asked, Newsom said that it was “wrong,” but that he had not abused his power by carrying on a relationship with a subordinate.

“The circumstances of that relationship was two consenting adults,” he said.

As Cox routinely refers to himself as a “Jack Kemp Republican,” Newsom has his own anachronistic label: “a Sargent Shriver Democrat.” He calls Shriver, an architect of Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty, “perhaps the most transformative figure of the 20th century.”

Newsom envisions himself as transformative for California. His proposal to usher in a state-run single payer health insurance program has received much of the attention—and the bulk of the scoffing from detractors. But he has other ambitious, pricey proposals.

He has called his “cradle to career” education plan, which includes expanded prenatal services and universal preschool, his top priority. He also touts a “Marshall Plan” for affordable housing and has set a statewide construction goal of 3.5 million new units within the next decade, a target most analysts dismiss as wildly unlikely.

But likely goals aren’t up to the task of fixing big problems. They’re also “not interesting,” Newsom says. And they don’t shift the terms of debate.

“(State Sen.) Scott Wiener, nonstop, he’s like so ‘here’s my thoughts on the 3.5 million,’ ” Newsom said. “It’s already the frame. The fact that we’re even having that conversation proves the success of at least establishing that benchmark and that goal. And that’s the point.”

After all, big hairy audaciousness has worked for him before.

Granted, his performance of same-sex marriages made Newsom politically toxic outside much of San Francisco for years, and, as even some allies argued, created a GOP wedge issue that helped President George W. Bush win re-election. But in retrospect, it seems an uncannily deft political move for someone with plans to run for governor in 2018.

“He read the tea leaves well,” said Bill Lee, the city administrator at the time.

Newsom and his defenders insist his motivation wasn’t political. Callan, who made a documentary about the occasion, recalls having brunch with his brother in-law just before he gave the order to the city clerk. “I’m about to ruin my political career,” Newsom allegedly told him. It didn’t.

Another success came in 2007, when his administration launched Healthy San Francisco, a subsidized health program for city dwellers. Newsom has since cited it on the campaign trail, giving himself more credibility on single-payer. Critics argue it was former Supervisor Tom Ammiano who initially proposed the idea and did much of the grunt work to bring it to fruition. “Newsom is claiming credit for something he didn’t really do and didn’t support,” Ammiano has said.

But not all of Newsom’s audacious ideas panned out. As mayor, he wanted to introduce free Wi-Fi across the city. He called for tidal turbines to be installed under the Golden Gate Bridge. He gave a YouTube State of City speech in 2008 that went on for more than seven hours.

Even some of Newsom’s allies concede that he wasn’t always intimately involved with the day-to-day.

“He’s more of a big picture guy,” said Lee. “I never, ever…got a sense from Gavin about details.”

That wasn’t always the case. In his first term as mayor, Newsom took his department heads on a tour of a public housing project in the city’s Hunters Point neighborhood, ordering them to fill potholes, replace dumpsters and fix bullet-ridden basketball backboards.

But over the years, said Corey Cook, a long-time Newsom observer who is now the dean of the School of Public Service at Boise State University, Newsom adopted a different approach to leadership: “Here’s what I need to do, you guys work out the deal.”

That may seem at odds with Newsom’s reputation as a policy expert, with a memorized statistic and academic jargon always at the ready. But, according to Cook, “he didn’t master the details of those policies and then say, ‘now let’s go work out these negotiated deals about how to make it work.’” Instead, it was ”off to the next big idea.”

Former colleagues of Newsom’s in San Francisco were sharper tongued.

Chris Daly, a former San Francisco supervisor who regularly clashed with Newsom, says the former mayor’s penchant for “regurgitating irrelevant statistics” and business-school lingo was merely a tool to “obfuscate” when politically useful, adding “I sat next to Gavin for two years on the Board and have too much personal experience to be a believer” in him as some sort of progressive hero. Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom takes the oath of office in 2015, pictured with his wife, Jennifer Siebel, and two of their four children.

Others, many of whom declined to speak on the record, recall him as image conscious, thin-skinned, uninterested in the behind-the-scenes work of governance, and incapable of playing well with others.

These days, Newsom acknowledges missteps from his mayoral years. He says he was impulsive (“a lot of it was ready, fire, aim, as opposed to ready, aim, fire”) and acknowledged, “when you’re younger you tend to want to take credit for everything.”

Whatever growing up Newsom has done in the intervening decade he attributes to being a father.

Newson’s first marriage with Kimberly Guilfoyle—a former prosecutor and Fox News anchor who is now dating Donald Trump, Jr.—ended in 2006. Two years later he married Jennifer Siebel, a feminist documentary filmmaker. They have four kids, ages 2 to 8.

In his first year as lieutenant governor, which Newsom easily won after his failed run for the top job, he received a crash course on the position’s limited scope. After accompanying California Republicans on a trip to Texas to learn about Gov. Rick Perry’s approach to economic growth, he then churned out a 10-part plan to goose California’s sluggish economy. Gov. Brown ignored it.

Not that Newsom hasn’t at least tried to make the job interesting.

“He has made more of it than anyone in my professional recollection—not just on the boards on which he sits, but the bully pulpit behind which he stands,” said Carl Guardino, president of the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, a high-tech business interest group that funded the economic report.

To the extent Newsom has left a mark, it has been by taking big, controversial positions. He was the only statewide politician in 2014 to endorse Proposition 47, a ballot measure that reduced an array of felonies to misdemeanors. He also led an initiative to require background checks on ammunition purchases (leading to a spat with then-state Senate leader Kevin de León, who sought to pre-empt the initiative with legislation). And Newsom was a driving political force behind the legalization of marijuana.

“I think Gavin is happiest when he’s focused more on the big picture,” said Stanford’s Humphreys. “He will, I suspect, thrive in that aspect of the gubernatorial role, but will also need a team of trusted nerds around him to make sure his vision is matched by appreciation of the grainy details.”

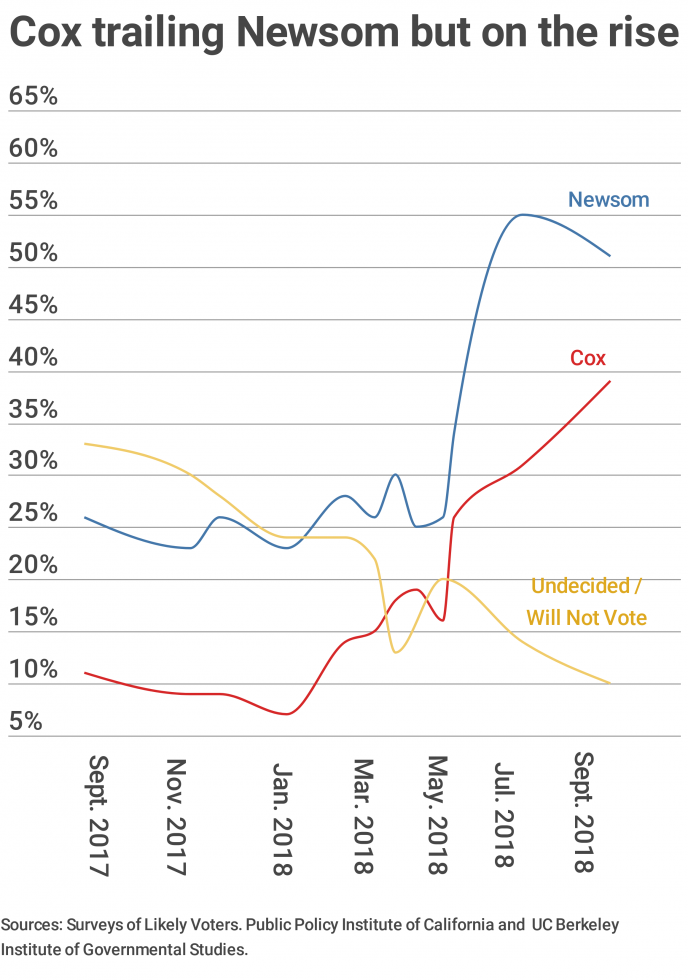

If you believe the numbers, Newsom will likely get the opportunity. Two weeks out from the election, he leads in public opinion polls and has raised roughly $44 million to Cox’s $14 million. Another $11 million has been spent in support of his campaign, with most of the money coming from organized labor groups and the health insurance industry.

On a mid-October Sunday, Newsom met at Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf’s headquarters in the city’s Grand Lake neighborhood for a mid-morning pep-rally. Both are Northern California politicos who, having incurred the public contempt of President Trump, are seen nationwide as key players of the anti-Trump Resistance, even if they are considered moderates in their hometowns.

But while Schaaf stuck to standard, accessible prose to energize the crowd, Newsom’s speech was like a cross between an undergrad lecture and a poetry slam.

He wags his outstretched index finger and thumb to punctuate his sentences, seamlessly dropping statistics and acronyms—along with the occasional “g.” He extolls California’s diversity with talk of “practicing pluralism” and the state’s “web of mutuality.” When he endorses early childhood education, he speaks of the synaptic “pruning” of the infant brain.

If the crowd isn’t following along, they don’t show it. But sometimes even reporters are stumped by the intricacies of Newsomian English.

Rather than use a word like “perspective,” for example, Newsom favors “frame.” “Situational,” likewise, means “short-term.” He speaks of “iterative processes,” “foundational principles,” and policymakers who “lack intentionality,” when most humans might simply say “trial and error,” “values” and “don’t have a plan.”

To his most ardent supporters, Newsom’s love of jargon is a testament to his analytical brain and his prodigious memory.

“He knows how to strike an inspirational note but he also knows how to get down in the weeds,” said Nathan Ballard, a former spokesperson.

Others are more skeptical of his shtick. While on a tour promoting Citizenville, a book he co-authored on how government can make better use of technology, Newsom was confronted by an unimpressed Stephen Colbert on his satirical late night political show, The Colbert Report.

“You’ve seen the contours of this change with the media, you’ve seen it certainly in the music industry,” Newsom said, trying to explain the thesis of the book. “Big is getting small and small is getting big.”

In a display of exasperation, Colbert flipped toward the back of the book. “Is there a bullshit translator?…What are you talking about?”

A book review in the San Francisco Chronicle was kinder: “breathless and dizzying (and often disconnected), but ultimately powerful.”

Which some might say is a pretty good description of Gavin Newsom himself.

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.