Dayton, Ohio, gave the world the Wright Brothers and the electric cash register. As recently as 1990, manufacturing jobs there were the backbone of the local economy. But in the two decades since, the area has lost thousands of blue-collar jobs, and the local housing market still wears the scars of the foreclosure crisis.

Those attributes make the city representative of the Rust Belt malaise that carried Donald Trump to his electoral college victory. Montgomery County, composed of Dayton and its environs, opted for President Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012. This year, the county favored Republican Trump over Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton by 1.3 percentage points, or about 3,000 votes.

But the demographics that shifted to the real estate mogul’s favor in places like Dayton may be short lived. Health-care companies and Internet marketers are powering a nascent knowledge economy in the Ohio city, one that also boasts an innovation district seeking to lure tech companies from more expensive locales. City developers have spent recent years trying to replicate the success of the Cannery Lofts, a trendy Dayton rental building carved out of an old downtown warehouse. And there are three new microbreweries and a handful of historic districts where listings pitch homes to “urban pioneers.”

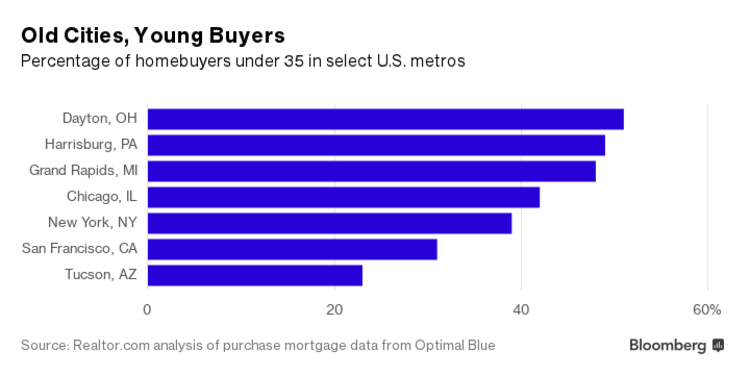

That mix of urban renaissance and bargain real estate has made the city appealing to young workers. During the first 10 months of this year, 51 percent of homebuyers were under 35 years old. That’s the highest share in the U.S., according to a Realtor.com analysis.

Clinton’s loss despite her 2.5 million popular-vote lead over Trump illustrated the concentration of traditional Democratic voters in a handful of coastal states. Will the appeal of cheap housing help Midwest cities such as Dayton attract young, well-educated workers? And if they do, will they change the political culture of states that turned away from the Democrats on Nov. 8?

Millennial voters backed Clinton, though not to the same degree they opted for Obama. Homeowners, meanwhile, are more likely to make it to the polls than renters, according to census data. It’s not unreasonable to think that a cohort of millennial homeowners clustering around smaller, affordable cities could be a bulwark for Democrats in future elections.

Amanda Hensler, 32, and her husband Zach, 34, were Dayton-area natives who originally left town for jobs in New Jersey. “I was pregnant, wanted to come back home and be close to family,” she says of her return. In June, they bought a house in a Dayton neighborhood called historic South Park, where their mortgage payment is half their old monthly rent. Zach works from home for a Pittsburgh-based tech firm; Amanda, a former teacher, is working part time and taking care of the couple’s 17-month-old son.

There’s a good reason that Dayton is popular with young buyers: It’s cheap. The median listing price was $120,000 in October, according to Zillow, and home values are still below their 2008 peak. Real estate agents say that one issue complicating sales inside the city limits is finding lenders willing to make loans for less than $50,000. For those who can get a loan, a small army of local investors is fixing and flipping foreclosed homes.

None of this is unique to Dayton. The list of U.S. metros where young homebuyers are wielding the most heft in the housing market is full of post-industrial cities with well-built houses and pockets of economic promise. In a city such as Buffalo, N.Y., or Grand Rapids, Mich., a technology cluster or a successful medical center can set off a mini-real estate boom.

“If you think about the price of entry in these housing markets, it might be a $20,000 down payment,” says Jonathan Smoke, chief economist at Realtor.com. “In San Francisco, it might take 10 times that amount.”

One of the immediate reactions to the presidential election was the suggestion that Democratic voters could seek to influence the electoral college in future contests by moving inland. While such wholesale shifts seem as farfetched as predictions of an exodus to Canada, the one thing that does seem to motivate Americans—namely, money—seems already to be doing the trick.

There’s evidence that the big coastal housing markets are becoming too expensive for even well-paid professionals. Urbanism, meanwhile, is transportable. And thanks to wireless Internet, so is work. A big house in a small Midwestern city is something that a lot of coastal liberals can afford. And while older workers with families and established careers are unlikely to pack up their lives, younger people see cheaper cities as a chance for a foothold in the housing market.

“There’s clearly been a kind of cascading of young workers being forced out of some of the top metros and tech hubs and looking at this kind of city,” says Mark Muro, senior fellow at the Metropolitan Policy Program at the liberal-leaning Brookings Institution. “They often bring a blue sentiment with them.”

“You could argue that it’s already happened in Colorado and Nevada, where the exodus of Californians has drastically shifted the statewide politics,” says Aaron Renn, a senior fellow at the politically conservative Manhattan Institute.

On the East Coast, North Carolina has attracted Democratic voters from more expensive states. Whether smaller middle America cities can have the same effect on their states may depend on whether they attract workers from outside the region. Cities such as Dallas and Nashville have become draws for relocators across the country, Renn says, but Midwestern metros such as Columbus and Indianapolis have mainly attracted residents from within Ohio and Indiana.

“I think the question of whether people are homeowners or not is less important,” says Jed Kolko, chief economist at job-listing site Indeed.com. “The bigger point is that younger people were more likely to vote for Clinton than older people were. If the age mix shifted younger in many of the older manufacturing towns, it would probably move their votes bluer.”

Not all young people are alike, of course. Adam Martin, 32, a partner at Dayton real estate firm Loxley Martin, recently sold a house to a 19-year-old pizza delivery employee. “Someone like that can buy a house for $60,000 and have a mortgage payment that’s lower than his rent,” he says. Those kinds of young buyers probably have less impact on the culture of the city than college-educated professionals who move in from out of state. Nevertheless, Martin says he believes Dayton’s downtown revival was being powered by a youthful population that would shift political preferences to the left.

“I think the culture is changing,” he says. “There’s a younger generation that’s getting out there and fighting for what they want and having a say in the community that they live in.”