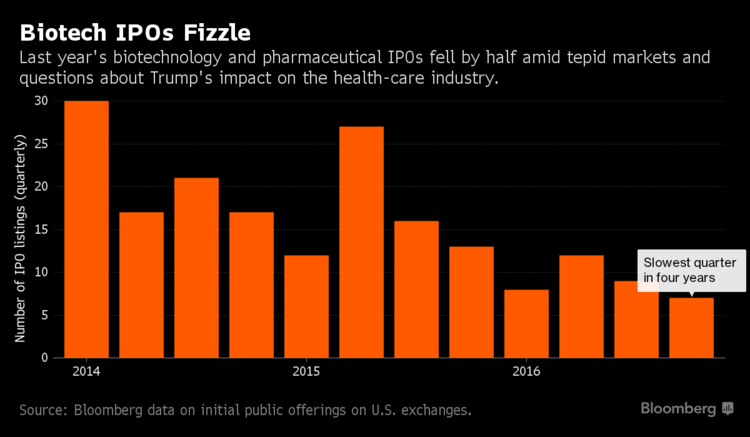

Last quarter was the slowest three-month period for drug company initial public offerings in four years, according to Bloomberg data. And in all of 2016, only 36 biotech and pharmaceutical companies went public in the U.S., according to data gathered by Bloomberg, compared with 68 in 2015 and a record 85 in 2014.

The long drought comes ahead of the health-care industry’s biggest gathering of companies and investors, the J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference in San Francisco, which began Monday. The week before the massive conference typically serves as a launchpad for fresh offerings. This year? Nothing.

“Biotech had a difficult year generally from a performance perspective, and so a bunch of the generalists have exited the market and money’s become much tighter,” says Bryan Roberts, a partner at Venrock, a technology and health-care venture capital firm with about $3.1 billion under management. “When people’s comfort with risk goes down, IPOs are one of the first things to fall off the edge of the cliff.”

There are several reasons at play. The market has been in a slump: the Nasdaq Biotechnology Index of 164 companies was down 22 percent in 2016, the first year-long losing streak since 2008 and the worst year since 2002. And with a new president taking office and promising to cut taxes and overhaul the health-care system, bankers and investors may be choosing to wait and see.

‘A Bit Spoiled’

“I think in the 2014 to 2015 period we were a bit spoiled as an industry,” says David Sabow, a managing director at Silicon Valley Bank. “After two consecutive years of a very liquid market, we thought that may be the new normal, but 2016 showed us that was not the case.”

Only $444.1 million was raised in U.S.-listed biotechnology and pharmaceutical IPOs during the fourth quarter of 2016 as seven companies went public, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

In 2016, seven U.S. biotechnology and drug companies announced their intent to go public in the first eight days of the year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Not a single one has raised their hand so far this January. Bruce Booth, a partner at investment firm Atlas Venture, says he’s not worried about that holdup.

“If the ‘new normal’ is a steady flow of 25-plus biotech IPOs each year, that would be a sign of a very healthy, maturing sector,” Booth says. “We should start to see a few IPOs by end of January or early February. I’d anticipate four to five of them by the end of February.” Booth’s fund, which manages around $700 million, has investments in gene editing firm Intellia Therapeutics and cancer drugmaker Unum Therapeutics.

Trump Bump

There could also be a pickup thanks to the broader stock market surge that has followed President-elect Donald Trump’s election victory. The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index is up 6.4 percent since the Nov. 8 election day.

“CEO confidence is a critical factor in driving M&A,” says Richard Landgarten, Barclays Plc’s head of healthcare and real estate banking. “Right now they feel good about the stock market broadly and, for example, the potential for pro-business tax reform from the new administration.”

Several biotech names have been floated for 2017 IPOs, including Jounce Therapeutics and Braeburn Pharmaceuticals, which have announced their intention to go public in the coming year without giving an exact date.

IPOs could also be prodded if takeovers increase in the industry. Big drugmakers have been sitting on cash left overseas, waiting on potential tax reform from Trump and Republicans in Congress. They’ve promised to lower rates, which could help repatriate $98 billion of overseas cash among large pharma companies, according to Jefferies analyst Jeffrey Holford.

Cash Waiting

Johnson & Johnson has about $40 billion overseas, followed by Merck & Co. with about $20 billion, then Pfizer with nearly $15 billion, according Holford’s Nov. 9 note to clients. Some of that money will stay invested abroad and the rest could be brought back for potential acquisitions.

“The smartest money in this space is watching the first 100 days” of the Trump administration, Sabow says.

Andy Weisenfeld, a partner at health-care investment banking firm MTS Health Partners, says he expects 2017 to be similar to 2016, with drugmakers letting smaller biotechs take the risks of research and development, then stepping in to snap experimental products once they’ve proven themselves.

“Prices for the better targets might go up, but if something

hasn’t been de-risked, I think for the most part these companies

would rather pay more and have it de-risked then pay real money

and have it fail,” Weisenfeld says.