Many people wouldn’t think twice about paying big bucks for perfectly cooked Chilean sea bass at a high-end restaurant or serving it to their boss at an elegant dinner party.

But would they feel the same confidence paying a premium price for something called Patagonian toothfish? Probably not, which is why in the 1970s an American fish merchant named Lee Lantz gave the toothfish its new name, turning it from a throwback fish that isn’t even a member of the bass family — it’s actually a cod — into a prized catch.

The toothfish is hardly the only fish to be rebranded as a means of separating consumers from their cash. But far more nefarious kinds of outright fraud have long been a problem across many food items. “This is a serious problem that affects all kinds of foods,” says UC Davis Food Science and Technology professor Moshe Rosenberg. “Fresh produce, wines, olive oil, processed foods, you name it.”

The Grocery Manufacturers Association in Washington, D.C., estimates that as much as 10 percent of all food products sold around the world is intentionally misrepresented or adulterated, such as diluted with some lesser quality ingredient. Estimates vary greatly as to the dollar amount behind this deception, but the GMA believes food fraud costs the global food economy up to $15 billion a year. Consumers bear much of that pain, but so do growers, producers and retailers.

Adulterated foods can also lead to illness and even death. A case of diluted milk and infant formula in China in 2008 led to an estimated 300,000 infants and young children becoming ill and six reported deaths. And at least 20 people died in Costa Rica this year from drinking adulterated alcohol. Those are only a fraction of the cases from around the world.

After more than four decades as a James Beard Award-winning food writer, cooking teacher and cookbook author, Sacramento resident Elaine Corn can suss out sleights of hand around food. Corn wrote about the widespread adulteration of extra-virgin olive oils (a scandal exposed in 2007 by The New Yorker) in The Sacramento Bee, Capital Public Radio, NPR and other major news outlets. Her reporting helped inspire the olive oil industry and California to adopt new standards for product quality in 2014.

While better standards and more consumer information were definitely good things, Corn says the deceptions that sparked them can destroy consumer confidence in the food system. “One of the backlash consequences of the revelations about extra-virgin olive oil is that people became afraid to buy it,” she says. “They were all thinking they were going to get ripped off.”

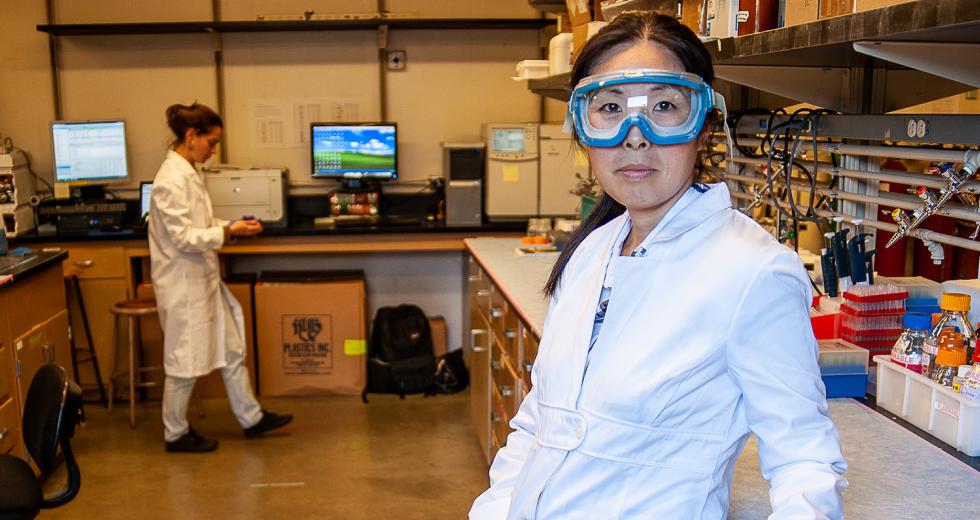

Ph.D. candidate Hilary Green prepares a sample to measure oil

oxidation at the UC Davis Olive Center.

Few California industries are as focused on policing their own products as olive oil, perhaps due to the negative media attention over the past decade. And it gets a big hand from Selina Wang, research director at the UC Davis Olive Center, where, among many things, she has helped to establish the authenticity standards by which California olive oil is now judged.

The problem with olive oil, Wang says, is that there is a fine line between something intentionally altered and something unintentionally mishandled into becoming a different product than advertised. A seminal report by UC Davis researchers published in 2010 brought attention to issues related to olive oil quality. Wang says while much of the attention focused on the finding that 69 percent of the olive oil tested did not meet U.S. Department of Agriculture standards for being extra-virgin, reporters and consumers skipped over the most likely reason: oxidation.

“A lot of the news stories essentially said the olive oil you’re buying is fake,” Wang says. “But what the report actually says is that many of these imported oils were probably oxidized by the time they were consumed. That’s very different from something being fake.”

Wang points out that extra-virgin olive oil eventually oxidizes with age, rendering it no longer true extra-virgin oil. As she sees it, extra-virgin olive oil mistakenly placed on a shelf for too long — or up high where heat can negatively affect it — isn’t the same as intentionally selling a product diluted with cheap soy oils colored with chemicals like industrial chlorophyll.

Rosenberg believes the European Union is well ahead of the United States when it comes to addressing challenges relating to food authenticity or fraud. The United Kingdom even has special police enforcement units to deal with food fraud. But with supply chains now globalized and with so much money to be made, stopping it is a herculean task.

A student prepares an oil sample to test for its quality at the

UC Davis Olive Center.

Herculean, but not impossible. Rosenberg says tools exist that allow scientists like him to identify the specific “fingerprints” that confirm oils, seafood and spices are actually what consumers think they are. By examining food down to the molecular level, researchers can build a biological profile to determine a product’s authenticity. But doing that requires a level of testing and data collection over a course of years, and that takes money. More importantly, it takes the political will to go after violators the way some other countries do.

“Unfortunately, I do not see at this time a similar effort in the U.S. in general and California in particular to stop fraud, and we need to do it,” he says. “We are a major agricultural producer, and we have to protect our products, and we have to protect our farmers. And we have to protect California products from being wrongly accused of being involved in food fraud somewhere else in the world.”

Chelsea Minor, director of consumer and public affairs for Raley’s, says verification by the retailer is critical in preventing fraud. While the company doesn’t have a tracking system for every item in its stores, she says “we do complete comprehensive analysis on Raley’s private label items,” and it does sample testing on seafood products, which are at a high risk of mislabeling or fraud.

A 2016 study from the ocean conservation group Oceana indicates that about 20 percent of all the fish obtained from grocery stores, restaurants and seafood markets was mislabeled. Inexpensive white escolar, for instance, is often substituted for far pricier tuna. An earlier Oceana study, in 2013, found that 38 percent of all the “red snapper” sold in Northern California was actually the much more common rockfish.

“We are a major agricultural producer, and we have to protect our products, and we have to protect our farmers. And we have to protect California products from being wrongly accused of being involved in food fraud somewhere else in the world.” Moshe Rosenberg, food science and technology professor, UC Davis

“We send about a hundred samples each year to a certified independent laboratory to identify their species,” Minor says. “As of today, 100 percent of our fish species tested was correctly labeled.”

Rick Mindermann, store director for Sacramento’s landmark Corti Brothers grocery market, says one way for customers to feel confident they’re buying the real deal is to shop at stores they know take pride in developing trusted sources in their supply chain.

“We work hard to develop good relationships with all of our vendors,” Mindermann says, noting they are always looking for red flags that might indicate a supplier is cutting corners. “We’re probably more inquisitive with our vendors than some other outlets. Darrell Corti still tastes every bottle of wine this store sells.”

—

Discuss this story and others on our Facebook page; “like” Comstock’s on Facebook by clicking or tapping here.

Recommended For You

Watching What You Eat

UC Davis scientists work to ensure safety of U.S. food supply

Within the past year alone, dozens of foodborne disease outbreaks have impacted the U.S. food supply, implicating all sorts of ingredients. Contaminated cucumbers have been blamed, along with tomatoes, cilantro, pork, turkey, tuna and raw milk. Cases have also occurred at the food-service level, often because employees failed to wash their hands.

Foodie Incubator Coming to Sacramento

The Food Factory founders aim to set up shop in Alkali Flat by 2020

Sacramento is on track to get a dedicated makerspace for food entrepreneurs who want to launch and scale their brands.