The greatest California cliché is a good thing gone awry. Fisherman’s Wharf is a maze of gaudy trinkets. Yosemite is where wild animals go to see humans in captivity. The traffic getting into Napa Valley is the first of many queues experienced in an afternoon there. Los Angeles.

Many wish their favorite places in California were deeply-held secrets. But there’s the hope that, given a little perspective, our current secrets can develop in a way that maintains the original character we fell in love with, without succumbing to the broad appeal forced by faceless investment. Right now, in Amador County, the Shenandoah Valley (which also extends into parts of El Dorado County) is at that postcard moment — the industry tide is swelling but not yet so oversaturated that visitors get lost in the waves.

Amador County is a patchwork of the rugged and serene. During the rainy months, the verdant rolling hills are pocked with vernal pools, mountain streams and more than a few cattle. In the dry heat of summer, the grass is a long blonde shag scarred with rocky crags and dry culverts braced by live oaks. In most places, you can hear little but the rustling of the wind. Dilapidated stacked-stone fences and foundations of old adobe houses built by the placer miners line the winding roads. In wetter years, you can ski in the morning and make it back for lunch until June.

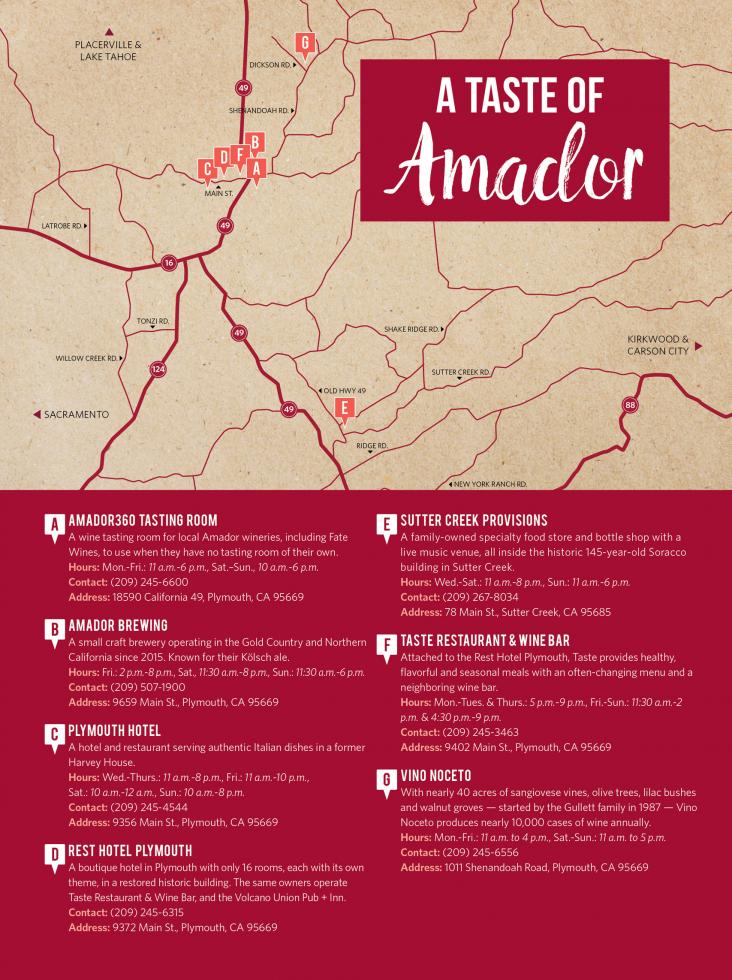

Amador360 serves as a tasting room for small wineries that lack

the capacity to open their own. It has a quaint, homey feel,

keeping with the local scene’s overall appeal.

Tucked there, in the storied foothills of the Sierra Nevada, lies a burgeoning wine scene. In actuality, it’s been burgeoning away since the Gold Rush: Amador County is home to the oldest vines in California. The Shenandoah Valley is famous for its zinfandels — “old-growth” vines. Its barbera and Rhone varietals are renowned as well. But according to the Amador Tourism Council, since 1869, when the region’s zinfandel vines were first documented, to the 1980s, only six wineries were registered in the county. Then came Vino Noceto, the seventh, whose Sangiovese vines matured in 1990.

Now there’s a new surge of interest in the area. The overcrowding of Napa has tasting groups in Plymouth — spread languidly across the bar at the Plymouth Hotel, which serves Vino Noceto on tap — lamenting. “You can’t even get in on a Monday in winter,” says one patron. There is a flurry of new wineries with different attitudes (and altitudes) focusing on different wines — from California heritage zinfandels to Iberian, Rhone and Italian varietals — being championed by roguish and talented winemakers and growers teeming with personality.

The small town of Plymouth calls itself the Gateway to the Shenandoah Valley, fitting given its position at the fork in the road between the valley to the north and the idyllic Highway 49 towns of Amador City and Sutter Creek to the south. There are now 47 wineries in the surrounding hills, the number growing every year. “And we still have plenty of space!” says the emphatic Maureen Funk, executive director of the Amador Council of Tourism and unfaltering fan of all things Amador.

Related - Infographic: California’s Wine Industry

Funk and her husband, Russ, who commutes to the East Bay, came to Amador over a decade ago from Southern California to raise children and fell in love with hiking, picnics and the many other opportunities to drink in the natural beauty. Around them grew a wine and food scene that, as it gains its footing all these years on, rivals some of the world’s most esteemed vintner regions.

As a region, this is a place that values its diverse microclimates as much as its diverse winemaking philosophies.

In Funk’s view, the Amador wine scene’s biggest selling point is its sense of community and cooperation between veterans and newcomers. According to Funk, people make homes in Amador because they love the easy-going lifestyle and the downright drinkability of the place, and that’s indicative of the direction the region’s wines are headed: not toward exclusivity but toward accessibility.

Brian Miller and Deidre Mueller, who also own Amador360 and run

the Barbera Festival, take a break from managing the sold-out,

second annual Amador Four Fires Festival.

Sangioveses and barbera are among the most drinkable reds and few wineries sell anything above $30. The surprising Iberian newcomer, tempranillo, flows like water in the Spanish Rioja region of its origin. In Amador it’s bottled by at least seven wineries, including the up-and-coming Fate Wines, who blends it with floral grenache (as is common in Rioja), providing a peppery, currant finish to the flat, red fruit of the oak-aged tempranillo. St. Amant Winery, whose Tempranillo comes from single-origin grapes at their vineyard at the base of the foothills, manages to sustain both acid and a tobacco spice from grapes not known for either. As a region, this is a place that values its diverse microclimates as much as its diverse winemaking philosophies.

Brian Miller and his wife, Deirdre Mueller, who moved to Amador in 2001 from the Bay Area, run Amador360 Winery Collective and Tasting Room — representing wineries without their own tasting room — as well as the Barbera Festival and Amador Four Fires food and wine festival.

At Amador360, the couple sells local wines like sommelier-cum-winemaker Thomas Allan’s Fate Wines label. As a 700-case operation, it is handcrafted in small batches, like many of the wines offered. When asked what he sees for the future of the Amador, Miller is adamant that it won’t look anything like Napa. He notes that, with only a few exceptions, the owners in the area are families or small groups and the influx of outside investment has been from people who are attracted to Amador for the right reasons. That is, drawn not only by the wine business but by the small town feel and a way of life they’d like to share in preserving.

This year at the Four Fires Festival, Tracy (pictured) and Mark

Berkner of Taste Kitchen served spit-fired lamb with a cherry

chutney.

The Barbera Festival started in 2011 and features over 80 Barberas from across California. Through increased exposure to the needs of the growing industry, the festival led the couple to open the Amador 360 Winery Collective in 2013. In 2015, they launched the Amador Four Fires Festival, which features wines from the four regions around the world (Rhone, Iberia, Italy and California) whose grapes Amador wineries grow, paired with highly creative, historically relevant, wood-fired regional cooking.

All proceeds from Four Fires goes to the Amador County Fairgrounds, the longstanding centerpiece of local culture that hosts everything from rodeos to Friday Night Wine Tastings and 4-H meets, and, of course, the county fair. According to Mueller and Funk, the fairgrounds have been teetering on a financial cliff for decades.

But rather than spelunking for a jackpot, they decided to build a sustainable model. “My mandate was never to make money,” Mueller, who also works full-time as a systems analyst, explains as to why they’ve capped attendance at 2,000 despite selling out of tickets during Four Fires’ debut. “It was to provide everyone with the best possible experience.” And scaling up while maintaining Amador’s trademark accessibility makes the size of the events self-limiting, she says. They organize the pouring tables in a sort of panopticon and run flow models on traffic to make sure everyone can get a glass of wine in their hand or something hot off the grill without fighting a line.

So far it’s been an effective strategy. Even with everyone huddling under tents from a light rain at the sold-out second annual event in May, there was never the sense of overcrowding one immediately associates with a festival.

That focus on quality over quantity is seen throughout the county. Tracy and Mark Berkner, Southern California natives and lifers in the hospitality industry who met as line cooks in their 20s, stumbled on the gold rush charm of Plymouth while traveling almost 20 years ago and never left. They moved to Volcano in 1997 to open the St. George Hotel, a landmark from 1862. Ten years ago this past May, with the proceeds from selling the St. George, they opened the 80-seat Taste Kitchen, which has received national accolades from Wine Enthusiast Magazine and Zagat for its wine program. They serve small plates meant to be shared and offer an extensive wine list that skews sharply local, curated by none other than Thomas Allan, the aforementioned vintner at Fate. Taste’s menu is simple and approachable, yet elegant. The plates, like the baby kale salad with strawberries and strawberry mousse, are perfectly prepared and simply plated — the kale so young and tender you’d swear it had snow brushed off of it. (Pair it with the viognier from Fate Wines.) The dishes are designed to let you try each flavor individually as your palate works to suss it out of the paired wine, or to construct that perfect bite when you think you have it all figured out. And then order something else, pair it with something, and repeat ad infinitum.

Sutter Creek Provisions is a family-owned specialty food store

and live music venue.

“Tracy and Mark are incredibly talented and driven people with a true passion for providing a memorable experience,” says Allan, who has been sommelier at Taste Kitchen since 2010.

Rest Hotel Plymouth, the couple’s third hotel, opened on Valentine’s Day of this year. It consists of two 1930s buildings — 12 rooms — redesigned and modernized. The space between the old buildings forms the lobby and open courtyard which hosts nightly wine soirees. There is talk of local wineries offering sample bottles in the rooms and room service from Taste, right down the block. Weekends are booked long in advance.

When asked how she measures success, Tracy Berkner doesn’t hesitate. “Success for me is being able to open this hotel on Valentine’s Day, the busiest night of the year for our restaurant, and just know that everything and everyone is being taken care of over there. Mark and I sat in [the hotel] and ate takeout from paper bags. It was a really great feeling,” she says. As a veteran of Amador, and one with at least some measure of success under her belt, Berkner isn’t worried either about the the next generation of the region’s hospitality scene. She points to Fate Wines, Sutter Creek Provisions and Amador Brewing Company as the future stalwarts of the local zeitgeist, and she likes what she sees.

The historic Rest Hotel is Tracy and Mark Berkner’s third hotel.

The couple also owns Taste Kitchen.

Sutter Creek Provisions is an ambitious, curated picnic outfitter and wine bar that recently opened in an old trading post in Sutter Creek selling (in addition to wine) charcuterie, sandwiches and, of course, baskets. Proprietor Casey Sexton can be found hosting a radio show in the vault office of her shop, contributing records to the establishments regular “vinyl nights,” or picking up kegs from Will Pritchard at Amador Brewing, whose German kölsch could compete with any in the world. At Amador Brewing, which is already expanding after only a year in operation, Pritchard hosts local restaurants and caterers to grill out for a diverse crowd of families and food tourists. It’s comfortably shabby-chic by any brewery standards. And, as you would expect, they have several of the taps over at Taste.

As a veteran of the Shenandoah Valley, and one with at least some measures of success under her belt, Berkner feels happily obliged, and a bit honored, to be helping the next generation of the Shenandoah’s hospitality scene get their bearings. Whether it’s a late night call looking for an emergency plumber or a young entrepreneur looking for a sympathetic ear, Berkner is the one people come to.

“We really have a ‘rising-tide lifts all boats’ sort of thing around here. And that’s really what’s so special about this place,” Berkner says sincerely.

With all its natural beauty and friendly, talented people, there is no excuse not to go to Amador County. But do it before the tide comes in.