The economy and state budget woes have slashed millions of dollars from public transit, forcing hundreds of layoffs, service cuts and fare increases that have pushed the price of a bus ride in Sacramento to among the highest in the nation.

Now transit operators in California face even deeper cuts. Federal regulators have refused to let at least one light-rail expansion project move forward because Sacramento Regional Transit’s operating finances aren’t strong enough. Other agencies face the same threat to capital funding, and even the body that oversees Capitol Corridor trains between Auburn and San Jose is worried about losing federal grants because of uncertain finances.

Developers are worried, too. Uncertainty throws a wrench into long-range development plans along transit corridors to help the region grow and thrive without choking in suburban sprawl and traffic. Such ills can make a region less attractive for new businesses or expansion.

“No country in the developed world has figured out how to have a booming economy without a vibrant, robust transit system,” says Mike McKeever, executive director of the Sacramento Area Council of Governments. The budget proposal by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger to permanently eliminate dedicated state transit funding is “a missile aimed right at the heart of growth,” he says.

SACOG’s blueprint for sustainable development in the Capital Region stresses denser urban style development in pedestrian-friendly areas with access to transit. It encourages such “transit-oriented development” of homes and businesses along transit routes, and several developers have embraced the notion with projects or plans along light-rail lines, such as the F65 project at Folsom Boulevard and 65th Street in Sacramento, the Historic Folsom Station development and Township 9 in Sacramento’s River District.

But transit-oriented development won’t work without reliable transit, and without TOD projects transit agencies lose a rich source of potential riders who could shore up their operating finances.

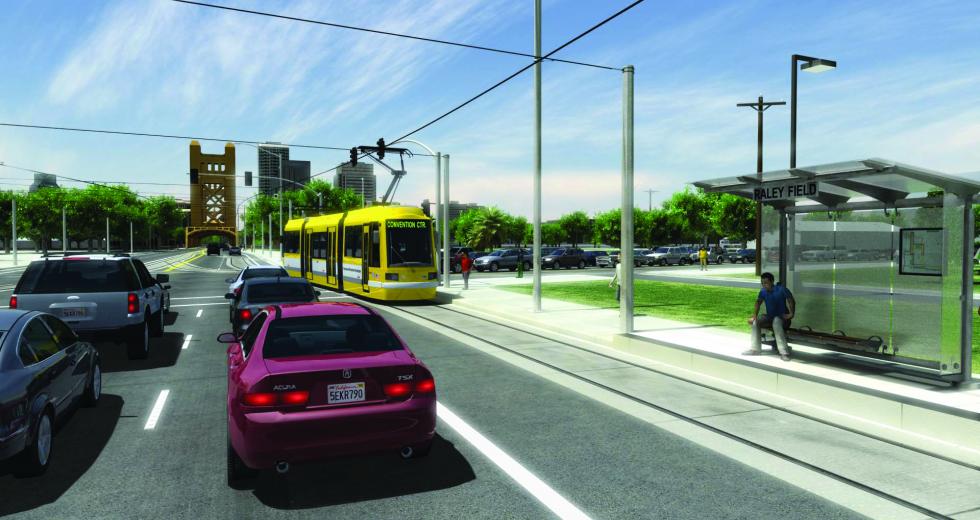

“We can’t hope to get people out of their cars unless we’ve got a reliable transit system,” says Mark Friedman, president of Fulcrum Property Group in Sacramento. Fulcrum is behind the F65 project and won approval Feb. 3 to move forward with plans for the Bridge District in West Sacramento. The Bridge District is planned around a proposed streetcar line that would give as many as 10,000 residents a car-free way to quickly reach downtown Sacramento.

“It’s close to the business district, but not close enough to walk,” Friedman says of the development area along the Sacramento River south of Tower Bridge. “If we don’t have a reliable transit system, then those people will need to have cars. … It completely changes the character of a neighborhood,” affecting everything from traffic management to community open space and parking.

Transit operators increasingly fear that scarce funding will not only gut current service — which saw a sharp increase in riders when gas prices climbed in 2008 — but also cripple expansion plans. Sacramento Regional Transit raised fares twice in 2009 to close gaps in its operating budget, but early this year the Federal Transit Administration lowered its rating of RT’s operating finances. That put the brakes on RT’s plans to expand the light-rail Blue Line south by 4.3 miles from Meadowview Road to Cosumnes River College. Construction was to start this spring, bringing hundreds of jobs; now RT must raise its financial rating before it gets the federal go-ahead. RT has already issued 60 layoff notices and is working with federal officials on a plan to quickly raise the rating.

“It doesn’t mean that the project is dead,” says Mike Wiley, general manager and chief executive of RT, but the rail extension that was to open in 2013 now won’t run before mid-2014.

“There are still plenty of transit-oriented development opportunities along existing lines,” says Gladys Cornell, a Folsom consultant who chairs the Urban Land Institute’s advisory council on TOD. But delays to expanded transit will likely delay development tied to those expansions, she says. “It’s an incredibly frustrating time” because the Obama administration is friendly to transit and construction prices are low, but state and local transit funding has dried up, she says. “It’s going to be a very challenging next couple of years just to find the money to keep operating transit, let alone expanding it.”

“I’d be hard-pressed to assume that any developer who has bought into this [transit-oriented development] idea would proceed with a project if they weren’t sure the transit would be running,” says Brian Williams, executive director of the Sacramento Transportation Authority, which oversees the Measure A local sales tax for transportation.

The state’s intercity commuter rail routes are also at risk from financial uncertainty. When billions of dollars in federal grants were made available for high-speed and intercity rail last year, the application required a commitment of dedicated operating funds for at least five years, says David Kutrosky, managing director of the Capitol Corridor Joint Powers Authority. “We signed an application stating that to be true,” he says.

But it’s a different story under the governor’s budget proposal for 2011. Another $2.5 billion in federal money will be up for grabs with similar requirements, but “I have to fill out a similar application and I can only show two years” of dedicated funds. Texas couldn’t show dedicated operating funds in the last round, so the Lone Star State didn’t get a dime, Kutrosky says.

The economic downturn and the state’s complicated hodgepodge of funding streams for transit have created this crisis. Many of those involved in the debate say ultimately a new system to fund California transportation is needed to fix things. But, they say, the state’s entrenched govern-by-crisis pattern and politics make it more likely that we’ll see even more complicated attempts to fund transit via the ballot box, and cities and counties may have to make hard decisions about whether to pay more to keep buses and trains running.

Until recently, transit funding in California came from a

complicated mix that included:

•Fare revenue

•Local sales taxes such as Sacramento’s Measure A, a

half-cent-on-the-dollar tax of which about 40 percent goes for

transit and paratransit

•State sales tax on gasoline and diesel fuel

•“Spillover” sales taxes when more than a certain amount is

collected, which varies widely depending on the price of fuel.

Much of the state funding came through the State Transit Assistance program, established in the early 1970s. But starting in the 2007-2008 budget year, the state began diverting money from STA for other uses such as school bus operations that traditionally had been paid from the state General Fund. The California Transit Association sued, arguing that more than $3.5 billion had been illegally diverted, and won. But the state has not restored the money, and the governor’s 2010-2011 budget would restructure the fuel excise taxes and sales tax, effectively and permanently eliminating the dedicated state transit funding.

“This is mind-boggling,” Sen. Alan Lowenthal, a Democrat from Long Beach and chairman of the Senate Transportation Committee, said at a Jan. 21 hearing on the governor’s proposal. “Last year we put a knife in the heart of transit financing; this year you propose to bury it completely.”

Mark Monroe, a principal program budget analyst with the state Finance Department, told the Senate Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review there was nothing to prevent paying for transit from the General Fund. That huge state budget has been running a multi-billion dollar annual deficit for years, and the governor’s proposal would generate less money for transportation than the current system does for about the next decade. “It’s a way of balancing the budget,” Monroe said. As of mid-February, Democrats in the Legislature were working on an alternative to the Schwarzenegger plan that would allow a local fee for transit on gasoline sales, along with changes to sales and fuel taxes.

The California Transit Association is working with the League of California Cities and the California Alliance for Jobs to qualify a measure for the November 2010 ballot that would force the state to stop raiding funds for local services such as transit and libraries.

RT’s budget troubles really began with the state raids of transit funding, Wiley says, and they got worse as the recession cut sales tax revenue by almost 20 percent. Even with service cuts in 2008 and two fare hikes in 2009 — the base fare for RT is now $2.50, among the highest in the U.S. for a system that doesn’t charge based on travel distance — ridership stayed high until about a year ago. That’s when layoffs and state furloughs started to really bite, Wiley says.

“In the short term, we need the state to restore the State Transit Assistance funding. … In the long term, we’re going to need a good solid increase in local funding,” whether through a higher sales tax, a local vehicle license fee or some other measure. Other cities in California foot more of the bill for local transit; while RT gets less than 40 percent of the half-cent Measure A tax, Los Angeles charges 1.5 cents-per-dollar in local transit sales tax, Wiley says.

West Sacramento in 2008 voted in its own half-cent sales tax to fund transit, and the city in February was preparing a federal application for $25 million to build the streetcar system that would serve the Bridge District. The city should have an answer by late spring, and the project could start construction in 2012.

Friedman says construction will begin this year whether or not the streetcar grant is approved. “I’m hopeful that as we move into better economic times we’ll find a path to a solution (to keep transit running),” he says.

Recommended For You

The Conductor

The California High-Speed Rail Authority replaced an engineer with a political operative to lead the nation’s biggest public works project. Jeff Morales instantly charmed his opponents but made technical decisions that placed high-speed rail at the mercy of the courts. Can Morales save his runaway train?

The Price of Progress

San Joaquin farmers protest bullet train

City dwellers driving past the expansive cotton fields and scattered farmhouses along Highway 43 to Corcoran might get the feeling they’ve left California. A haze of dust, bugs and little particles of cow dung blanket the road between Fresno and Bakersfield. Even on a nice day, wiping debris from a car windshield begins to feel futile.